Advertisement

So-Called 'Witch Caves' Suggest Underground Network Helped Accused Witches Escape Salem

Salem is well known for its gruesome history of witch trials and the stories of those executed in the anti-witch hysteria.

But it's also believed that there was a network of people in the area who secretly worked to help those accused of witchcraft escape from Salem to safety.

Local historians say that in 1693 some people suspected of witchcraft traveled to what is now the Framingham/Ashland area to hide in "witch caves."

Sarah Bridges Clayes, whose name was sometimes recorded as Clay or Cloyes, was likely one of those people. She fled to the area after escaping from jail while awaiting her sentence on witchcraft charges in Salem.

Clayes' two sisters had been executed on similar charges.

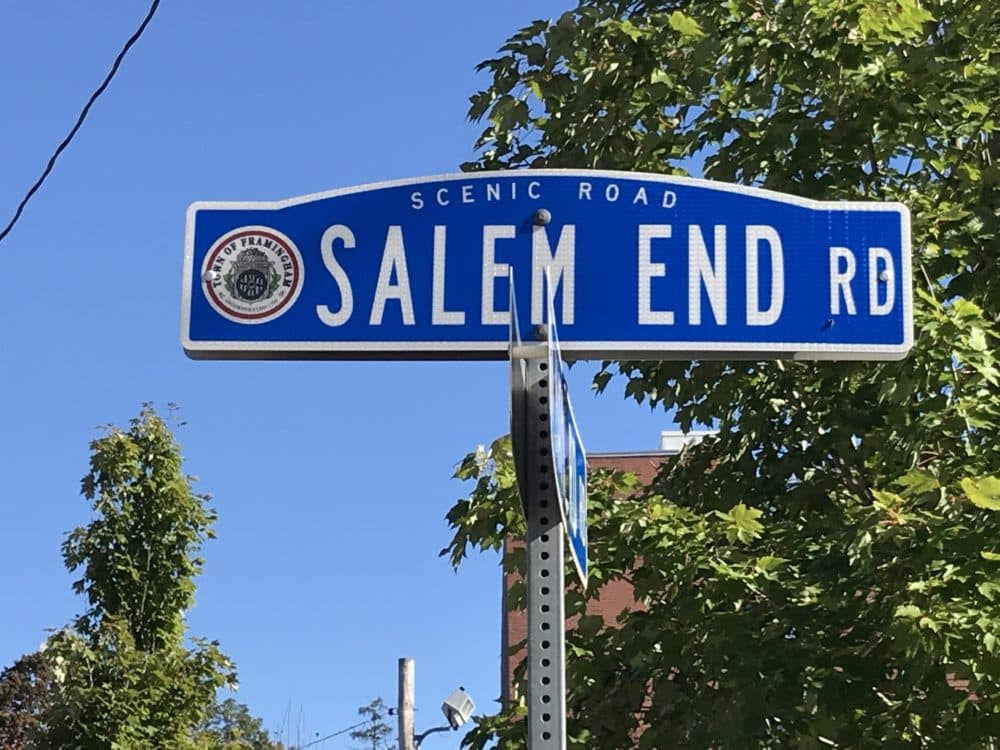

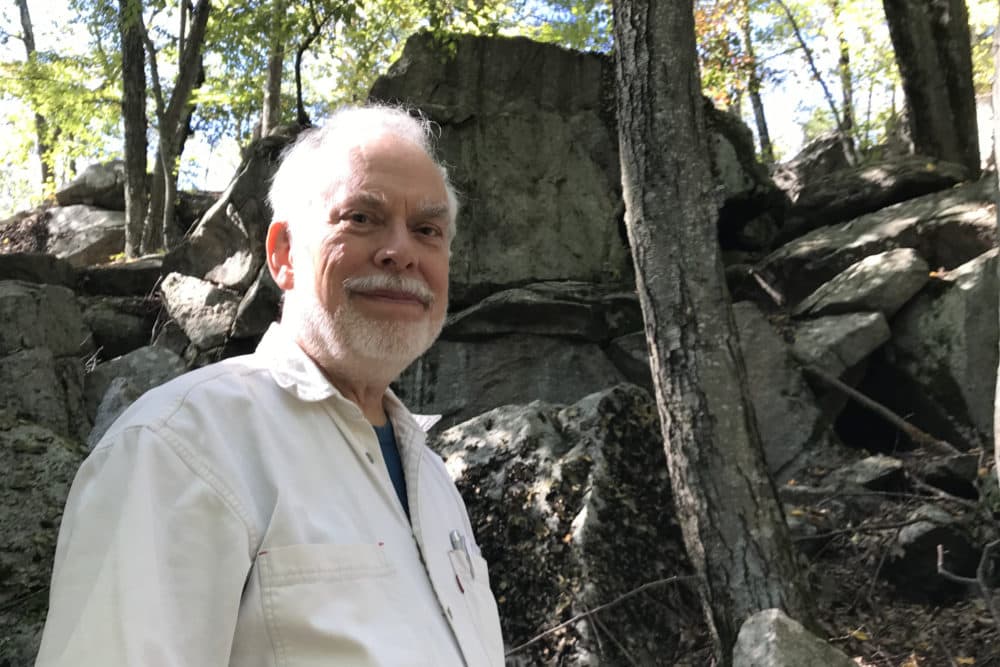

Historians suggest Clayes hid out in rocky spots in the Ashland woods after escaping. Rob St. Germain, a member of the Ashland Town Forest Committee, says those caves still exist, just off of the aptly titled "Salem End Road."

"Clayes spent at least a winter here," St. Germain said. "Some recounts suggest they were here two years, in the cave ... letting the political process in Boston catch up with the bad situation in Salem and put an end to it."

Once they left the caves, Clayes and her husband built a home, which is now officially in Framingham. Today, the Clayes' home is still standing and under renovation. It's one of the five so-called "witch houses" in the area.

St. Germain said people fleeing were likely looking for property owned by former Deputy Gov. Thomas Danforth, who was a judge in Salem. Danforth was also a member of the Salem Witch Tribunals, but he left Salem because he felt uncomfortable about the proceedings.

Danforth gave 800 acres of land to those who had been accused.

"The Danforths were sympathizers, friendly," St. Germain said. "They were rational, educated people."

Town property records provide another piece of evidence that the area was a safe haven for those accused of witchcraft.

The Township Petition for Framingham from 1700 shows at least 50 people related to Clayes and her sisters had resettled to the area.

Guest

Rob St. Germain, a member of the Ashland Town Forest Committee.

This segment aired on October 26, 2018.