Advertisement

'After Emily' Introduces The Women Who Brought Emily Dickinson's Poetry To the World

Emily Dickinson is considered one of most original voices in poetry and as one of the founders of a uniquely American poetic tradition.

But the world may have never known her had two women — Mabel Loomis Todd and Millicent Todd Bingham — not devoted their lives to editing, promoting and selling Dickinson's work.

This mother-daughter duo takes their turn in the spotlight in the new book, "After Emily. Two Remarkable Women and the Legacy of America's Greatest Poet."

Book Excerpt: "After Emily: Two Remarkable Women and the Legacy of America's Greatest Poet."

By Julie Dobrow

Who was Emily Dickinson? A shape- shifter confronts us as scholars and acolytes, though we continue to seek answers: How much of the poet’s life can we discern from her poetry? Which of the many word and phrasing possibilities she offered did she truly intend in her poems? Why did she partially secede from the world? Did she really wear only white? Can anyone ever truly know Emily Dickinson?

Perhaps two women came closest to understanding the enigmatic poet: Mabel Loomis Todd and her daughter Millicent Todd Bingham, the women arguably most responsible for bringing Emily Dickinson to the world through their editing and publishing of her poems and letters, as well as their scholarly analysis of her work. As of this writing, neither Mabel nor Millicent has before been the subject of a full- length biography, and each of them led fascinating lives. By elucidating Mabel’s and Millicent’s stories, I hope also to shed new light on how Dickinson’s work was presented to the public and the effect their efforts had on Emily’s enduring legacies. Understanding their own stories and influences, as well as their complicated mother/daughter relationship, helps push Emily’s door ajar a bit farther.

Mabel’s and Millicent’s considerable work on Emily Dickinson began to shape both the image of the poet and the contours of her poetry as we know it today. Mabel edited and published three volumes of Emily Dickinson’s poetry, and two volumes of her letters, as well as a reissue of the letters at the centennial of the poet’s birth. Millicent was responsible for editing and publishing one additional volume of poetry, and wrote three other books about the poet’s craft and life. During her lifetime, Mabel worked tirelessly to promote Emily’s poetry, which included carefully honed marketing campaigns and innumerable public talks about the poet intended to build intrigue and promote sales. Millicent, as heir to her mother’s unfinished Dickinson business and all of the original Dickinson manuscripts in her possession, found herself in the improbable position of navigating between high- powered forces fueled by long- simmering internecine tensions; her tortured decisions ultimately meant that Emily’s papers reside in different repositories across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

That Emily Dickinson’s poetry first came to be published in 1890 in a volume coedited by Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson is relatively well known; the stories behind it are not. And these stories help to broaden the world of Emily Dickinson by illuminating the lives of others central to her universe. Mabel’s work editing and promoting Emily’s poetry not only cast her public image but also figured into a complicated web of relationships between members of the Dickinson family and the Todds whose animosities have lasted for generations. And importantly, the narrative of “Emily Dickinson’s literary debut” (as Millicent would later refer to it) is inextricably linked to the narratives of Mabel and Millicent, themselves. Mabel’s and Millicent’s Dickinson work became a driving and significant force for each of them, so central that it irrevocably recast their professional directions, so powerful that it irreversibly altered their personal lives.

By seeing events through the minds of Mabel and Millicent as revealed in their own words, a new context for the life and times of Emily Dickinson emerges. Mabel first learned of Emily Dickinson when she arrived in Amherst in the early 1880s. She later came to know the woman known as “the Amherst myth” through her close associations with the Dickinson family, including her life- altering relationship with Austin, which roiled everyone in both families. We better understand, in light of this, how Emily’s sister, Lavinia, came to entrust the publication of her poems to Mabel— then later betrayed this trust and launched a lawsuit that became a much gossiped- about scandal. We see how Millicent was shaped by her mother’s affair and larger- than- life persona, and how they ultimately hewed the path not only to Millicent’s work on Dickinson but also to her inability to find true love and career clarity. We realize in turn how Millicent’s own discontents influenced her readings of Emily. We learn how the personal relationships each woman had affected her outlook on life— and her understanding of Dickinson. We comprehend that other aspects of Mabel’s and Millicent’s lives— Mabel’s passion for music and writing, Millicent’s precision and scientific rigor, the world travels each undertook— not only enriched their own lives and made them rare among female peers of their respective eras but also inspired their crafting of Emily Dickinson.

But perhaps most importantly, by more fully articulating these women’s inner lives, we can see various ways their worldviews affected their editing and interpretations of Dickinson’s work. The resonances Mabel and Millicent felt with Emily— all outsiders, all obsessed with writing about the meaning of nature and human experience, all women pushing up against the boundaries of their times— suggest new insights into why Emily’s work was important to them and how they portrayed both the poet and her poems.

Mabel Loomis Todd’s revising, ordering and titling of Dickinson’s poems and her regularizing of Dickinson’s punctuation in her poetry have long been contested among literary scholars and Dickinson fans. The ways in which Mabel altered spellings, gave some poems names, grouped them thematically rather than chronologically and at times even changed words to make lines that might have scanned or rhymed better but which possibly altered their meaning, have been the subject of many an academic debate. But the clever and cutting- edge ways in which Mabel designed and marketed the early volumes of Dickinson’s poetry— ensuring that these brilliant works that defied most conventions of nineteenth- century verse actually sold out in their first editions and went through several printings— have almost never been recognized or discussed.

These new perspectives are possible only because of the enormous reservoir of previously unmined and unpublished papers that both Mabel and Millicent left behind. Neither woman ever threw out a single scrap of paper; indeed, one of the major ongoing themes of the final three decades of Millicent’s life was her tormented quest to figure out what to do with all the STUFF— the hundreds upon hundreds of boxes of saved letters, diaries, journals, scrapbooks and photographs that had scrupulously recorded the lives of her grandparents, her parents and herself.

Eventually Millicent donated the great majority of these papers to Yale University. I have spent several years slowly making my way through the seven hundred- plus boxes of primary source materials that live at Yale’s Sterling Library, as well as uncovering materials that reside in libraries in Amherst, at Harvard, at Brown, and other repositories— even in the attic of an old house. Systematically reading Mabel’s and Millicent’s diaries and journals (each woman religiously kept both for many decades— Mabel for sixty- six years and Millicent for close to eighty) has given me insights into the lives, hopes and dreams of these women who so obsessively documented their lives. Sometimes I even had the great advantage of reading about the same event in each of their private writings, through each of their eyes and individual perspectives.

In their other extensive papers, I have unearthed some astonishing materials: among them, Millicent’s revealing notes from her psychiatric sessions that divulge why she felt compelled to take on her mother’s Dickinson work despite her own very considerable ambivalence, and Mabel’s lecture notes from the talks she gave on Emily Dickinson that helped craft a certain image of the poet and her work. I had the unique opportunity to read internal documents from Amherst College that shed new light on the battles over where Emily Dickinson’s papers would ultimately reside. None of these materials have ever been extensively cited in any published work. And the plethora of additional materials has yielded many other telling discoveries about these fascinating women.

These primary sources illuminate a set of captivating and intricately interconnected lives. This is ultimately a story about sorting through Mabel’s and Millicent’s papers to tell the full narrative of their lives, uncover their secrets, and see how they created mythologies and defined identities for themselves as well as for Emily Dickinson.

Mabel, who often reflected that hers was “the most positively brilliant life I know of,” came to believe that Emily Dickinson, too, lived a life with moments of dazzling vividness. It was a life she felt she understood, a torch whose shine she had seen. And yet for Mabel and for Millicent, the light of Emily’s life was still glimpsed only from a distance, shadows that emerged sporadically from her partly opened door.

Excerpted from AFTER EMILY: Two Remarkable Women and the Legacy of America's Greatest Poet by Julie Dobrow. Copyright © 2018 Julie Dobrow. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Guest

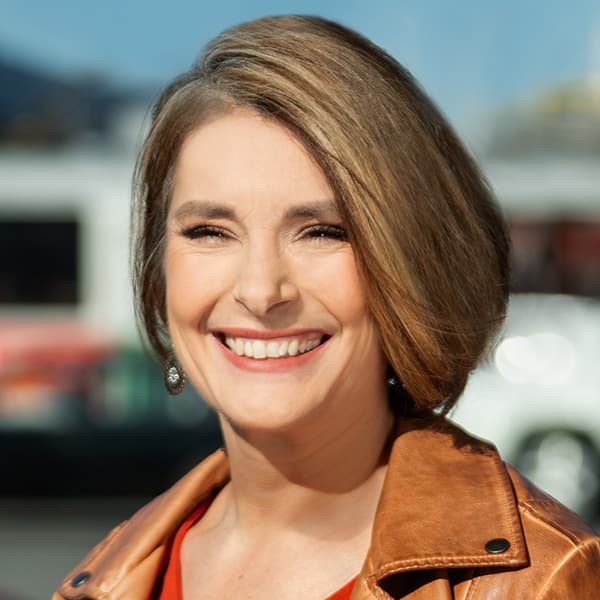

Julie Dobrow, author of "After Emily. Two Remarkable Women and the Legacy of America's Greatest Poet" and director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at Tufts University.

This segment aired on November 6, 2018.