Advertisement

How A Long-Forgotten Act Of Police Brutality Transformed A Federal Judge, U.S. President And Civil Rights In America

After WWII, 900,000 African-American soldiers made their way back home.

One of them, Sgt. Isaac Woodard, was on his way back to his hometown in South Carolina, when he was ordered off a greyhound bus over a dispute about bathroom breaks.

Once off, a local police chief beat him so viciously he was permanently and completely blinded in both eyes — all while still in uniform.

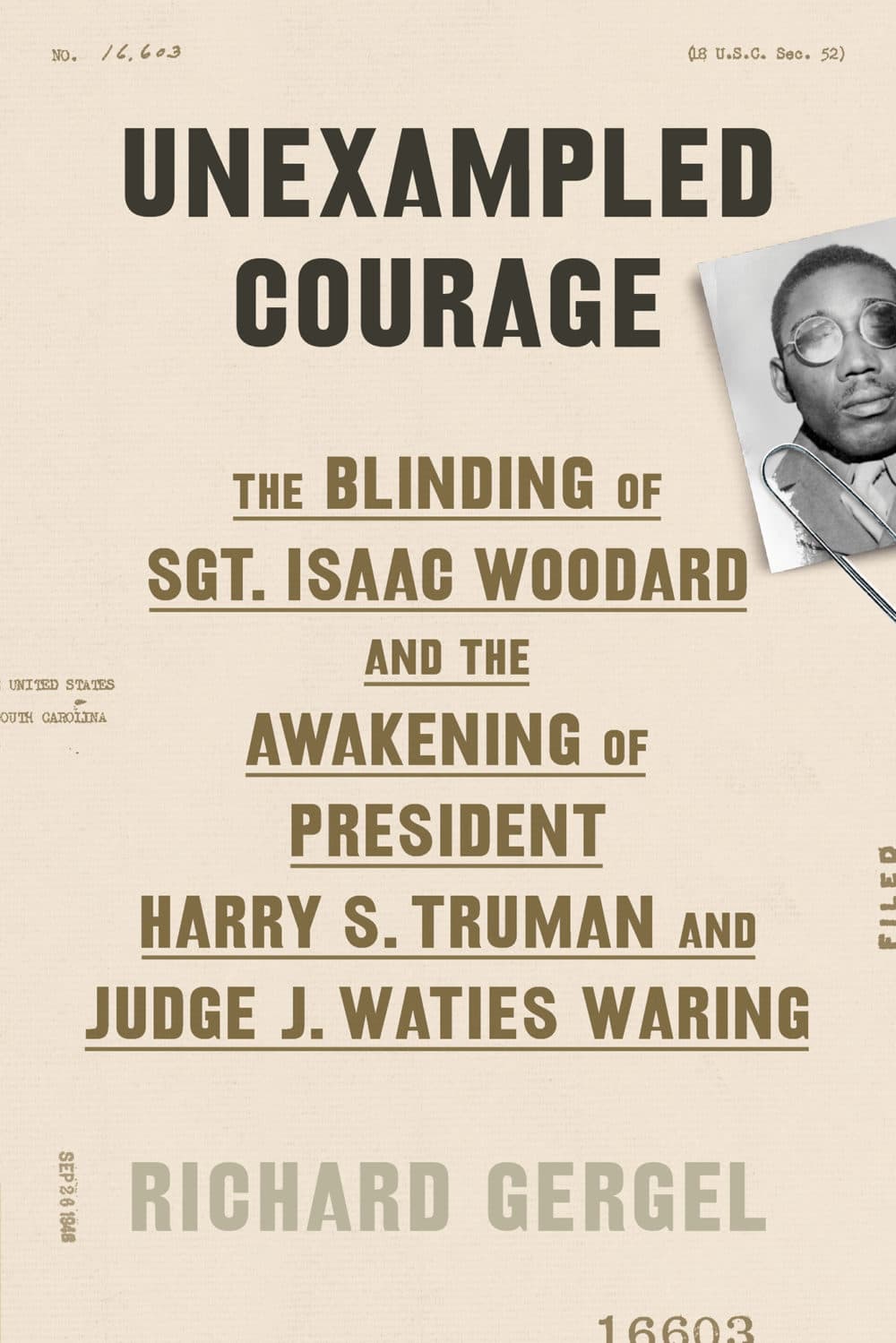

The story of his blinding — and what came after — is told in the new book, "Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring."

"Unexampled Courage" takes a deep dive into how a long-forgotten act of police brutality changed a federal judge, a sitting president and the course of civil rights in America.

Guest

Richard Gergel, U.S. district court judge in South Carolina, and author of "Unexampled Courage: the blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring."

Book Excerpt: "Unexampled Courage: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring."

By Richard Gergel

INTRODUCTION: A COLLISION OF TWO WORLDS

THE UNITED STATES emerged from World War II in ascendancy, having conquered Nazi Germany and imperial Japan. Looking over a war-ravaged world, American leaders sought to remake foreign governments in America’s own image, as democracies committed to individual liberty and human rights. But beneath the veneer of America’s grand self-image was a stark reality: African Americans residing in the old Confederacy lived in a twilight world between slavery and freedom. They no longer had masters, but they did not enjoy the rights of a free people. Black southerners were routinely denied the right to vote, segregated physically from the dominant white society as a matter of law, and relegated to the margins of American prosperity.

African Americans living in other regions of the country faced their own racial challenges. This gaping chasm between the ideal world envisioned by white Americans and the real world experienced by black Americans represented, as the Swedish economist and social scientist Gunnar Myrdal put it, “a moral lag in the development of the nation” and “a problem in the heart of America.”

Seen from today’s perspective, the American triumph over Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchisement might seem to have been inevitable, the collapse of morally indefensible practices wholly inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution. But in 1945, with southern state governments resolutely committed to the racial status quo and the federal government largely a passive bystander, there was no obvious path to resolving this great American dilemma. Something had to be done, but what, and by whom?

On February 12, 1946, Sergeant Isaac Woodard, a decorated African American soldier, was beaten and blinded in Batesburg, South Carolina, by the town’s police chief on the day of his discharge from the U.S. Army and while still in uniform. The brutality and injustice of Woodard’s treatment encapsulated the angst and outrage of the nation’s 900,000 returning black veterans, who felt their service in defense of American liberty was not appreciated. Soon, protests and mass meetings in response to the Woodard incident were held in black communities across America. Civil rights leaders demanded federal action to hold the police officer accountable for Woodard’s brutal treatment and to protect the rights of the nation’s black citizens from racial violence. Demands for action soon reached the doorstep of the new president, Harry S. Truman, and placed him in the crosswinds of Roosevelt’s disparate New Deal coalition, which included southern segregationists and newly emerging black voters in critical swing states outside the South. Although counseled by his staff and political allies to stay away from divisive civil rights issues, Truman responded to the Woodard blinding by directing his excessively cautious Department of Justice to act. Within days, the department charged Lynwood Shull, the police chief of Batesburg, with criminal civil rights violations and began the process of establishing the first presidential committee on civil rights, to address the widespread reports of violence against returning black veterans. Truman’s civil rights committee would, within the year, issue a report recommending a bold civil rights agenda, culminating in Truman’s historic executive order in July 1948 ending segregation in the armed forces of the United States.

The Justice Department’s prosecution of Shull before an all-white jury in the federal district court in Columbia, South Carolina, resulted in the police chief’s quick acquittal. But the jury’s failure to hold the obviously culpable police officer accountable profoundly troubled the presiding judge, J. Waties Waring, and sent him on a personal journey of study and reflection on race and justice in America. Within months following the Shull trial, Waring began issuing landmark civil rights decisions, then unprecedented for a federal district judge in the South. Despite blistering public denunciations, death threats, and attacks on his home, Waring persisted in upholding the rule of law in his Charleston, South Carolina, courtroom, including his 1951 dissent in a school desegregation case, Briggs v. Elliott, in which he declared government-mandated segregation a per se violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Three years later, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court would adopt Waring’s reasoning and language in Brown v. Board of Education, destroying the legal foundation of Jim Crow segregation.

While conducting research for this book, I came across a statement attributed to the legendary civil rights leader Julian Bond in which he asserted that the Isaac Woodard incident ignited the modern civil rights movement. Intrigued, I contacted Bond in September 2014 to hear his explanation of that statement. I shared with him the connection of the Woodard incident to the racial awakening of President Truman and Judge Waring and asked if that was the basis of his statement. Bond explained that while my research tended to confirm his statement, he had meant to express the belief that the tragic circumstances of Woodard’s blinding had inspired a generation of African Americans to action. He then recalled from memory the story of Woodard’s blinding and described a photograph he remembered from his childhood. As Bond described the image, he began to weep openly over the telephone. Composing himself, he apologized for his tears but stated that after all these years “I still weep for this blinded soldier.”

The power of the Isaac Woodard story moved people of goodwill to act in the postwar era and still had the force to move Julian Bond to tears nearly seventy years later. In the end, Woodard’s blinding would open the eyes of many Americans, black and white. This is a story that deserves to be told, with all its pathos, its brutality, and its redemption of the American system of justice.

1. A TRAGIC DETOUR

AS THE CLOCK struck 7:00 p.m. on August 14, 1945, President Harry S. Truman assembled the White House press corps in the Oval Office. The ebullient president, standing behind his desk, informed the reporters that earlier that afternoon the Japanese government had unconditionally surrendered, bringing an end to World War II. The reporters spontaneously burst into applause and then raced for the door, to share this historic announcement with the rest of the nation. Thousands gathered in Lafayette Square across from the White House to celebrate, and soon there were calls of “We want Truman! We want Truman!” The president came onto the North Portico of the White House to make a few remarks. “This is a great day,” Truman declared, “the day we’ve been waiting for. This is the day for free governments in the world. This is the day that fascism and police government ceases in the world. The great task ahead [is] to restore peace and bring free government to the world.”

Over the ensuing months, millions of American soldiers returned home. Among them were nearly 900,000 African Americans who believed that their service and sacrifices in the defense of American liberty might provide them with their rightful place in America’s “free government.” While black soldiers had been assigned to segregated units and frequently given the most menial tasks, their wartime service afforded them opportunities for education, leadership, and recognition. Many of those serving in Europe had experienced respectful treatment from local citizens and realized the possibility of living in a world where skin color was not the defining characteristic of one’s life. And many returning black soldiers, regardless of where they had served, were resolved to no longer acquiesce in the indignities of racial segregation and disenfranchisement that had characterized their prewar lives.

However, the stark reality was that three-fourths of the black veterans were coming home to communities in the old Confederacy. This was the world of Jim Crow, where black citizens were relegated to the margins of American democracy and expected to be the bootblacks and mudsills of the nation’s economy.

Beginning in the 1890s, southern state and local governments started adopting a vast number of what came to be known as Jim Crow laws mandating segregation in almost every aspect of civic life. These statutes and ordinances were validated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld a Louisiana law requiring racially segregated railway cars. In the years following Plessy, laws were adopted requiring racial separation in factories, parks, public transportation, hospitals, restaurants, and even cemeteries. The clear message was that black citizens were not fit to be in the presence of white people except as maids, laborers, and yardmen.

The widespread adoption of these Jim Crow laws followed the election of a new generation of racial demagogues across the South, a generation bent on defeating the old planter class that had long controlled southern politics and promising the complete subjugation of black citizens. Once they were in power, state legislatures under their control moved swiftly to adopt a vast array of laws to prevent African Americans from voting. Black disenfranchisement was accomplished through an endless variety of tricks and devices denying access to the ballot, including “grandfather clauses,” poll taxes, “understanding clauses,” literacy requirements, all-white party primaries, and old-fashioned terror and intimidation. Despite the protection of the Fifteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1898 decision of Williams v. Mississippi upheld various Mississippi state constitutional provisions that effectively disenfranchised all black voters in the state.

The clash between the expectations and demands of returning black veterans and the unforgiving racial practices of the Jim Crow South would soon produce widespread conflicts.3 Although the Jim Crow system sought to maintain the separation of the races, encounters between blacks and whites were a daily reality of southern life. Public transportation, including buses, trains, and trolleys, was shared, but strict rules governed where blacks could sit and when they must relinquish their seats to white customers. Many black servicemen and recently demobilized soldiers resented and resisted these Jim Crow practices, and public transportation became a flash point for racial tensions.

In July 1944, Booker T. Spicely, an African American private on leave from Camp Butner, was shot and killed in the nearby town of Durham, North Carolina, by a bus driver after he refused to relinquish his seat to a white passenger. That same month, Second Lieutenant Jack Roosevelt Robinson had a confrontation with a civilian bus driver in Killeen, Texas, near Camp Hood, when he refused an order to move to the back of the bus. Lieutenant Robinson faced a general court-martial over the incident but was acquitted after a full trial. Americans would come to know the young lieutenant three years later by his nickname, Jackie Robinson, when he broke the color line of Major League Baseball.

As African American soldiers in large numbers returned stateside in early 1946, reports of racial incidents on public transportation increased. One soldier stationed at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, refused in February 1946 to sit at the back of the bus as directed by the driver. When the driver ordered him off the bus, the soldier cursed the driver. Several white passengers followed the black serviceman off the bus, attacked him, and broke his jaw. In another incident that year, an African American corporal, Marguerite Nicholson, was arrested in Hamlet, North Carolina, after she refused to move to a segregated car once her train crossed into the segregated South. She was beaten by the local police chief in the course of her arrest, spent two days in jail, and was fined $25. A black airman stationed at a base near Florence, South Carolina, was arrested because he sat next to a white woman on a bus.

On the cool winter night of February 12, 1946, Isaac Woodard Jr. climbed aboard a Greyhound bus in Augusta, Georgia, on his last leg home to Winnsboro, South Carolina, from a journey that had begun in the Philippines several weeks before. Woodard, who was twenty-six years old, had just completed an arduous three-year tour in the U.S. Army, where he served in the Pacific theater, earned a battle star for unloading ships under enemy fire during the New Guinea campaign, and won promotions, ultimately to the rank of sergeant. One of nine children of Sarah and Isaac Woodard Sr., he was born on March 8, 1919, on a farm in Fairfield County, South Carolina. The county was an impoverished, majority-black community in the central part of the state. The Woodard family, as landless sharecroppers, was on the lowest rung of what was essentially a feudal society. The family struggled to subsist, and the Woodard children frequently worked in the fields rather than attend school. Isaac junior quit school at age eleven, after completing the fifth grade, and left home at fifteen in search of relief from the family’s crushing poverty. His mother would later observe that Fairfield County whites, who owned virtually all of the land and wealth of the community, did not “think of a Negro as they do a dog. Looks as if all they want is our work.”

Woodard worked in North Carolina for a number of his early adult years, doing $2-a-day construction jobs, laying railroad tracks, delivering milk for a local dairy, and serving in the Civilian Conservation Corps. As World War II approached and it appeared likely he would be inducted into the armed forces, he returned to Fairfield County and briefly took a job at a local sawmill, Doolittle’s Lumber, while he awaited his induction notice. He worked as a “log turner,” a backbreaking and dangerous job that earned him but $10 a week. Because they faced such dismal employment options, it is not surprising that despite the perils of service in the armed forces, Woodard and many other African Americans residing in the rural South viewed military service as a promising alternative.

Woodard entered service at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, on October 14, 1942, as a private and did his basic training in Bainbridge, Georgia. He was a member of the 429th Port Battalion, which shipped out in October 1944 for New Guinea, where he served as a longshoreman, loading and unloading military ships in the Pacific. The New Guinea campaign was a multiyear battle by the Allies, mostly Australians and Americans, to recapture New Guinea Island from a deeply entrenched Japanese army. The campaign involved some of the most arduous and intense fighting of the war, and all armies suffered significant casualties. The Allies ultimately prevailed through a series of dramatic water landings devised by General Douglas MacArthur.

Isaac Woodard was part of a segregated support unit during the major New Guinea maritime landing operations, and his unit took intense enemy fire and casualties as they performed critical operations. He showed solid leadership and won promotions to technician fifth grade, equivalent to the rank of corporal, and later technician fourth grade, equivalent to the rank of sergeant. He received the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. As the army demobilized, Woodard was given an honorable discharge notice and traveled from Manila to the United States by troopship, arriving in New York on January 15, 1946. After transport by troop train to Camp Gordon, Georgia, he was discharged nearly a month later, on February 12.

Now, a little more than three years after joining the army, Woodard was returning home with sergeant stripes on his sleeve and battle medals on his chest. Although at five feet eight inches and 143 pounds he was not a large and imposing man, his military service as a longshoreman had left him in top physical condition. Upon discharge, he was taking the Greyhound bus from Augusta, Georgia, to Columbia, South Carolina, and ultimately to Winnsboro, the seat of Fairfield County. There he was to be reunited with his wife, Rosa Scruggs Woodard, after several years of separation.

The Greyhound bus on which Woodard traveled was mostly filled with recently demobilized soldiers still in uniform who had been discharged only hours earlier from Camp Gordon. They were in a jovial mood as the bus progressed in the darkness through the small towns on its route—first to Aiken and then to the even smaller communities of Edgefield, Johnston, Ridge Spring, and Batesburg—with black and white soldiers mixing and socializing on the bus in a manner that likely made the few white civilian passengers and the white bus driver uncomfortable. The events that would transpire that fateful evening, both on and off the bus, would later be the subject of great dispute, but what is clear is that Sergeant Woodard displayed a degree of assertiveness and self-confidence that most southern whites were not accustomed to nor prepared to accept.

According to Woodard’s later account, his troubles that evening began with an angry exchange of words with the bus driver, Alton Blackwell. Woodard stated that he approached the driver during what was to be a brief stop to ask if he could step off the bus to relieve himself. Buses during this era did not have restroom facilities, and Greyhound drivers were instructed that any request by a passenger to step off the bus should be accommodated. According to Woodard, Blackwell responded, “Hell, no. God damn it, go back and sit down. I ain’t got time to wait.” Woodard stated that he responded to the driver, “God damn it, talk to me like I am talking to you. I am a man just like you.” He stated that Blackwell then reluctantly told him to “go ahead then and hurry back.” Woodard stepped off the bus and quickly returned without further words with the driver.

Blackwell later described a distinctly different set of events in his encounter with Woodard. He claimed that his disagreement with Woodard arose initially from the soldier’s repeated requests to leave the bus to relieve himself during what were scheduled to be brief stops in various small communities. According to Blackwell, these frequent exits by Woodard put the bus behind schedule for its arrival in Columbia, where many of the passengers were making connections. Blackwell would later claim that he detected the odor of alcohol on Woodard and observed him drinking from a bottle of whiskey and then passing the bottle to a white soldier sitting next to him. As the evening progressed, Blackwell asserted that Woodard became increasingly intoxicated, profane, and disruptive. He claimed that after a white civilian passenger complained to him about Woodard’s conduct, he resolved to have the soldier removed from his bus at the next stop, which was in Batesburg, South Carolina. Apparently then unconcerned about staying on schedule, he exited the bus in search of a police officer to have Woodard removed.

Subsequent investigative interviews and sworn testimony of other passengers on the Augusta-to-Columbia bus offered conflicting accounts regarding Woodard’s behavior on the bus. Two soldiers, one black and one white, gave FBI agents sworn statements that they saw Woodard (and other soldiers) drinking on the bus, but both denied that Woodard was in any way disruptive. One civilian witness, a white woman, later stated that Woodard and a white soldier were sitting together, drinking, and “using language not becoming to a gentleman [that] should not be used in the presence of a lady.” No witness ever corroborated the bus driver’s claim that Woodard left the bus at every stop.

Batesburg was a small town of several thousand people, approximately half black and half white, nestled in the western portion of Lexington County, about thirty miles from Columbia, the state capital. It was an oddly situated town immediately adjacent to another small town and rival, Leesville, with their town business districts only approximately a hundred yards apart. As in most small southern rural communities of that era, whites controlled essentially all aspects of economic and political life, and blacks, disenfranchised and mostly impoverished, lived marginal existences and sought to avoid any conflict with the ruling white establishment.

Batesburg’s two-man police force was headed by Lynwood Shull, then forty years old, who had served as the department’s chief for nearly eight years. Unlike two of his brothers, Shull did not serve in the military during World War II. He was five feet nine inches tall, with blue eyes and gray-streaked brown hair. He tipped the scales at well over two hundred pounds and was sliding into middle-age obesity. He wore his police uniform essentially all the time, changing into a suit only for Sunday morning services at the local Methodist church. The Shull family was politically connected: Lynwood’s father had at one time served in a patronage position as supervisor of a local prison farm. Later, when an investigator from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) began looking into the Woodard incident, local African Americans privately expressed fear of the Shull family, citing incidents of excessive force by Chief Shull against black citizens and abusive actions by his father while running the prison farm.

Blackwell found Chief Shull with a younger officer, Elliot Long, sitting nearby in the town’s one patrol car. He reported that he had two soldiers, one black and one white, who were drunk and disorderly and he wanted them off his bus. The driver then climbed back onto his bus and informed Woodard he had someone who wanted to speak to him. Woodard complied, and as he exited the bus, the driver told Chief Shull that “this soldier has been making a disturbance on the bus.” As Woodard later recounted, he tried to explain to Shull his exchange with the bus driver, in which he was cursed by the driver and told to return to his seat when he asked for the opportunity to relieve himself. Before he could complete his explanation, Woodard stated, Shull removed a baton from a side pocket, struck him across his head, and told him to “shut up.” A black soldier sitting on the bus, Lincoln Miller, later gave the FBI an affidavit stating that he observed an officer “pull a black jack out of his pocket and hit Woodard over the head with it.” A white soldier, Jennings Stroud, told the FBI he saw a policeman “hit the colored fellow a fairly good lick which did not knock him down, but seemed to show the colored fellow [his] authority.”

Shull’s statements and testimony about when he first struck Woodard with his blackjack were inconsistent and would become a focus of attention at later criminal and civil trials. In Shull’s initial interview with FBI agents, he stated he first struck Woodard with his police-issued blackjack after walking a considerable distance from the bus stop and in response to the soldier’s allegedly refusing to continue walking with him to the city jail. Later, he changed his story and admitted that he “may have” struck Woodard with his blackjack at or near the bus stop, as observed by the two soldiers interviewed by the FBI.

Law-enforcement officers during this era routinely carried blackjacks, which were baton-type weapons, generally leather, with shotgun pellets or other metal packed into the head and with a coiled-spring handle. These devices were so common that most police uniforms came with a “blackjack pocket” along the pants leg. A leather strap at the base of the blackjack allowed an officer to secure the device to his wrist. The coiled-spring handle produced tremendous energy and a whipping force in the head of the device, which from time to time resulted in devastating injuries or death when an officer struck a citizen in the face or head. In an early 1990s federal appellate court decision, the court quoted expert testimony indicating that a blow from a blackjack to the head was “potentially lethal and … universally prohibited.” Shull’s blackjack strike to Woodard’s head near the bus stop that February evening—variously described as a “tap,” a “punch,” and a “good lick”—immediately quieted Woodard’s efforts to explain himself.

After striking Woodard in the head, Shull placed the sergeant under arrest and began escorting him to the town jail several blocks away. To secure him, Shull twisted Woodard’s arm behind his back and pushed him down one of Batesburg’s main streets, Railroad Avenue, and then right onto Granite Street to the jail. Shull left his other officer, Elliot Long, to question the supposedly drunk and disorderly white passenger, whom the driver was never able to reliably identify.

As the police chief and the soldier proceeded toward the town jail and out of sight, Woodard reported that Shull asked him whether he was discharged from the army. Woodard said that when he replied “yes,” Shull immediately struck him again on the head with the blackjack. The correct answer, Shull informed the soldier, was “yes, sir.” Woodard responded by grabbing the blackjack from Shull and wrenching it away. At that moment, in Woodard’s telling, Officer Long appeared with his gun drawn. Drop your weapon, he told Woodard—or “I will drop you.”

Woodard reported that when he complied with Long’s directive and allowed the blackjack to fall to the ground, Shull retrieved it and began to angrily beat him in the head and face. Woodard stated that he lost consciousness and lay on the ground for an unknown period of time. When he came to, Shull instructed him to stand up. As Woodard struggled to his feet, he reported, Shull struck him violently and repeatedly in one eye, and then the other, with the end of the blackjack, driving the baton “into my eyeballs.” The force used by Shull was so great that it broke his blackjack. Woodard stated he was then dragged into the town jail and placed in a cell, where he was the only prisoner present. Shortly thereafter, Shull and Long left for the evening, with Woodard in a semiconscious haze.

In his various statements and trial testimony, Shull denied beating Woodard repeatedly with his blackjack or driving the end of the weapon into his eyes but offered varied accounts regarding the number of times he struck him, the location where the strikes occurred, and the circumstances leading to the use of the blackjack. When first confronted about the incident by an Associated Press reporter, Shull stated that the soldier attempted to take his blackjack and he “cracked him across the head.” In his initial FBI interview, Shull claimed that he “bumped” Woodard with the baton after he refused to continue walking to the city jail. He claimed that after this “bump” with the blackjack, Woodard tried to wrench the weapon from his hand and, in self-defense, he struck Woodard a single time in the face with the blackjack. Later, Shull stated that while they were walking to the jail, Woodard “suddenly grabbed” the blackjack without any provocation, and he struck Woodard with the weapon once in self-defense. When confronted with these inconsistencies under cross-examination, Shull admitted he might have struck Woodard with his blackjack on three occasions: at the bus stop, while walking to the jail, and when Woodard attempted to take the blackjack from him.15

Shull denied that he beat Woodard into unconsciousness and left him dazed in the town jail overnight. Instead, he claimed that after striking Woodard with his blackjack one time outside the jail, he was able to move the soldier into a cell without further incident. He stated that Woodard voiced no complaints that evening about his eyes and was in good health when Shull left the jail. He also denied that Officer Long was present for any of his altercation with Woodard, which Long affirmed.16

When Woodard woke the next morning, he could not see. He had been awakened by Shull, who informed him he was due in city court that morning. This presented several practical problems. Woodard reported he was unable to see and needed assistance to move from one place to another. Further, the brutal beating of the night before had left his face covered with dried blood, which he could not see or remove without help. Shull led Woodard to the sink and cleaned him up for his court appearance. Then, said Woodard, Shull guided him to the city court to face a charge of drunk and disorderly conduct.

Woodard’s case was called by the Batesburg town judge, H. E. Quarles, who also served as the town’s mayor. Woodard attempted to explain to the judge the circumstances that had led to his conflict with the bus driver and with Chief Shull. Shull stepped in to inform Quarles that Woodard had attempted to take his blackjack on the way to the jail. Quarles responded by stating that “we don’t have that kind of stuff down here” and promptly found Woodard guilty. Woodard was given a fine of $50.00 or “30 days hard labor on the road.” He attempted to locate the money to pay the fine but had only $44.00 in cash and a check from the army for mustering-out pay of $694.73. According to Woodard, he wanted to endorse the check to pay the fine but was incapable of doing so because “I had never tried to sign my name without seeing.” The judge ultimately agreed to suspend the balance of the fine and accept payment of $44.00.17

Shull’s account of the morning differed. He denied that Woodard said he could not see, although one eye appeared “swelled practically shut” and the other was “puffed.” He claimed Woodard was able to negotiate himself over to the city court without assistance and could see sufficiently to count out the money in his pocket. According to Shull, when his case was called, Woodard stated he was guilty and “guessed he had too much to drink.” Judge Quarles would later testify that Woodard was able to see while in the city court that morning and that he pleaded guilty to the charge of drunk and disorderly conduct. Later medical evaluations of Woodard’s eye injuries made Shull’s and Quarles’s claims that Woodard could see that morning implausible if not medically impossible.18

With his court hearing completed and having paid the fine, Woodard was free to go. But according to Woodard, he was blind and incapable of navigating independently. He returned to the jail to lie down on a cot, telling Shull he felt ill. Shull attempted to locate the town physician, W. W. King, to see Woodard but was told the doctor was on a house call. Confronted with a prisoner who claimed he could not see as a result of traumatic injuries, and unable to obtain the assistance of a physician, Shull seemed at a loss for what to do next. One account had him repeatedly pouring water on Woodard’s eyes and asking after each application, “Can you see yet?” Shull testified he went to the town pharmacist for advice and was told to apply eyewash and warm towels until King arrived. He followed this advice, but Woodard did not improve.19

King showed up later that afternoon. He found both of Woodard’s eyes “badly swollen,” and when he opened the lids, “there was an escape of bloody fluid.” Although he prepared no medical record of his examination, he later testified that Woodard’s injuries were confined exclusively to his eyes, with swelling only over the eyelids and nose. He concluded that Woodard “had serious damage to both eyes” and “was badly in need of a specialist.” He recommended that Shull immediately transport Woodard to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Columbia, some thirty miles away. In compliance with King’s instructions, Shull loaded Woodard into the town’s police vehicle and drove him to the VA Hospital, telling the on-call physician that evening that Woodard had suffered his injuries as a result of an encounter with a police officer after being arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct.

Woodard was initially evaluated by the medical officer on duty, Major Albert Eaddy, who had trained as a psychiatrist. Eaddy immediately appreciated that Woodard’s condition was wholly beyond his expertise. Because the VA Hospital had no eye specialist, he summoned the ear, nose, and throat specialist, Captain Arthur Clancy, to Woodard’s bedside. Clancy observed that both of Woodard’s eyelids were black and blue and swollen, and there was massive hemorrhaging inside each eye. He was then able to determine that Woodard’s right cornea was lacerated. He did not note any other injuries that were visible in that initial examination. He would later diagnose Woodard with a rupture of his right globe and massive intraocular hemorrhaging to both eyes. He also indicated that Woodard’s remaining vision was “nil” and that there was no available treatment for his condition.

Woodard was seen the following morning, February 14, by Dr. Mortimer Burger, an internist, who conducted a full physical examination. Burger documented a history of Woodard’s having been beaten on the head by a police officer and knocked unconscious. He noted that Woodard’s eyelids were moderately swollen and tender, with a thick coat of pus and bloody material. When he pulled back the soldier’s eyelids, he observed hemorrhaging of the eyeballs. He also documented the presence of dried blood over Woodard’s right ear and swelling on the forehead and on the upper portions of his cheek. He noted that there was swelling over the nose but no gross deformities; a skull X-ray confirmed the absence of any fracture to the nose. Thus, Burger’s initial examination suggested that Woodard had suffered facial and head trauma greater than would be expected from a single strike by a blackjack. Because Woodard had bilateral blindness and lacked any fracture of the facial or nasal bones, a fair question was how Woodard could have been blinded in both eyes from a single strike of a blackjack.

Woodard remained at the VA Hospital for the next two months and was treated with antibiotics and other medications related to the traumatic injuries to his eyes. There was no treatment offered or recommended that would restore his vision. Upon his discharge on April 13, Woodard was diagnosed with bilateral phthisis bulbi “secondary to trauma,” which meant he had two shrunken, nonfunctioning eyes as a result of his encounter in Batesburg. The VA physicians determined that he was totally and permanently blind, unable to discern light sufficiently to tell when a 60-watt bulb was on or off. Woodard’s discharging doctors offered him no hope for future treatment and could only recommend that he attend a school for the blind.

While Woodard was hospitalized, VA staff applied for VA disability benefits on his behalf. But there was a major complication: Woodard had been discharged around 5:00 p.m. from Camp Gordon, Georgia, approximately five hours before suffering his disabling injury. Although he was still in uniform and had not yet reached home, VA rules at the time disqualified him from full benefits and limited him to partial disability benefits of $50 per month. (This denial of full pension benefits would later become highly controversial but would not be rectified for more than fifteen years, when Congress finally amended the law to allow full service-related disability for a soldier who suffered a disabling injury while traveling home after discharge from the military.)

As Woodard convalesced in the VA Hospital, his wife, Rosa, then living in Winnsboro, showed little interest in continuing their relationship. According to a Woodard family member, Rosa did not look forward to a future life with a disabled husband. Like many southern black families, Woodard’s parents and siblings had moved north during the war in search of greater economic opportunities, and the entire family now resided together in New York City. When Woodard was finally discharged from the hospital, two of his sisters traveled to South Carolina to gather up their blinded brother and bring him to the new family home at 1100 Franklin Avenue in the Bronx.

Life was a struggle for Woodard. He complained to his mother, “My head feels like it’s going to burst [and] my eyes ache.” He fumbled around the home, having no training for independent living as a blind person. His mother prayed nightly for some relief for her son, lamenting that a loss of a leg or arm would have been less devastating than the loss of sight.

The Woodard family resolved to seek specialized evaluation and treatment in the newly emerging field of ophthalmology to determine if there was any potential treatment for Isaac. Dr. Chester Chinn, America’s first African American ophthalmologist, examined Woodard in his Manhattan office on April 25, 1946. He determined that the structural injuries to Woodard’s eyes were more extensive than diagnosed by the VA physicians, finding that Woodard had suffered traumatic ruptures of both globes. This made any prospect for recovery essentially nonexistent. Chinn also diagnosed Woodard with “bilateral phthisis bulbi of traumatic origin” and rated his prognosis “hopeless.” For Sergeant Isaac Woodard, now twenty-seven, blinded, unemployed, abandoned by his wife, and limited to a VA pension below subsistence level, “hopeless” might have seemed an apt prognosis of his life ahead.

Excerpted from UNEXAMPLED COURAGE: The Blinding of Sgt. Isaac Woodard and the Awakening of President Harry S. Truman and Judge J. Waties Waring by Richard Gergel. Published by Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2019 by Richard Gergel. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on March 08, 2019.

This segment aired on March 8, 2019.