Advertisement

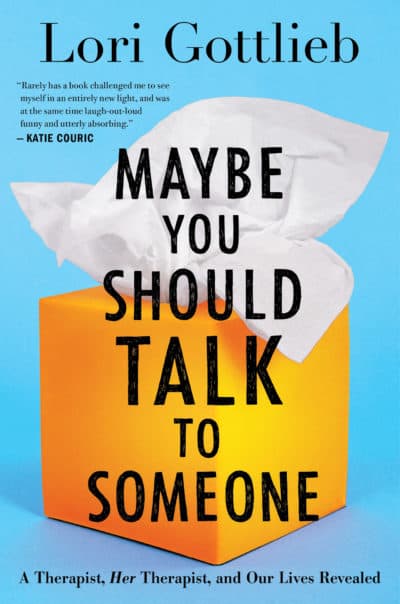

'Maybe You Should Talk To Someone': A Therapist In Therapy Shares Reflections In New Book

Resume

"Aren't therapists supposed to keep their personal lives private? Aren't they supposed to ... refrain from calling their patients names — even in their heads? Aren't therapists, of all people, supposed to have their lives together?"

Those questions are posed by psychotherapist Lori Gottlieb, who, as it happens, doesn't always have it together.

In her new book, “Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed,” Gottlieb tells the story of her patients' crises--and her own--to ask fundamental questions about therapy: what is, and what it isn't, and why it matters.

Gottlieb will be speaking at Brookline Booksmith in Brookline at 7 p.m. on Friday.

Guest

Lori Gottlieb, psychotherapist, writer for The Atlantic's "Dear Therapist" column, and author of “Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed." She tweets @LoriGottlieb1.

Book Excerpt: Maybe You

1

Chart note, John:

Patient reports feeling “stressed out” and states that he is having difficulty

sleeping and getting along with his wife. Expresses annoyance with others

and seeks help “managing the idiots.”Have compassion.

Deep breath.

Have compassion, have compassion, have compassion . . .

I’m repeating this phrase in my head like a mantra as the forty-yearold

man sitting across from me is telling me about all of the people in his

life who are “idiots.” Why, he wants to know, is the world filled with so

many idiots? Are they born this way? Do they become this way? Maybe,

he muses, it has something to do with all the artificial chemicals that are

added to the food we eat nowadays.

“That’s why I try to eat organic,” he says. “So I don’t become an idiot

like everyone else.”

I’m losing track of which idiot he’s talking about: the dental hygienist

who asks too many questions (“None of them rhetorical”), the coworker

who only asks questions (“He never makes statements, because that would

imply that he had something to say”), the driver in front of him who stopped at a yellow light (“No sense of urgency! ”), the Apple technician at

the Genius Bar who couldn’t fix his laptop (“Some genius!”).

“John,” I begin, but he’s starting to tell a rambling story about his wife.

I can’t get a word in edgewise, even though he has come to me for help.

I, by the way, am his new therapist. (His previous therapist, who lasted

just three sessions, was “nice, but an idiot.”)

“And then Margo gets angry — can you believe it?” he’s saying. “But

she doesn’t tell me she’s angry. She just acts angry, and I’m supposed to ask

her what’s wrong. But I know if I ask, she’ll say, ‘Nothing,’ the first three

times, and then maybe the fourth or fifth time she’ll say, ‘You know what’s

wrong,’ and I’ll say, ‘No, I don’t, or I wouldn’t be asking! ’ ”

He smiles. It’s a huge smile. I try to work with the smile — anything to

change his monologue into a dialogue and make contact with him.

“I’m curious about your smile just now,” I say. “Because you’re talking

about being frustrated by many people, including Margo, and yet you’re

smiling.”

His smile gets bigger. He has the whitest teeth I’ve ever seen. They’re

gleaming like diamonds. “I’m smiling, Sherlock, because I know exactly

what’s bothering my wife!”

“Ah!” I reply. “So —”

“Wait, wait. I’m getting to the best part,” he interrupts. “So, like I said,

I really do know what’s wrong, but I’m not that interested in hearing another

complaint. So this time, instead of asking, I decide I’m going to —”

He stops and peers at the clock on the bookshelf behind me.

I want to use this opportunity to help John slow down. I could comment

on the glance at the clock (does he feel rushed in here?) or the fact

that he just called me Sherlock (was he irritated with me?). Or I could stay

more on the surface in what we call “the content” — the narrative he’s telling

— and try to understand more about why he equates Margo’s feelings

with a complaint. But if I stay in the content, we won’t connect at all this

session, and John, I’m learning, is somebody who has trouble making contact

with the people in his life.

“John,” I try again. “I wonder if we can go back to what just happened —”

“Oh, good,” he says, cutting me off. “I still have twenty minutes left.”

And then he’s back to his story.

I sense a yawn coming on, a strong one, and it takes what feels like superhuman

strength to keep my jaw clenched tight. I can feel my muscles

resisting, twisting my face into odd expressions, but thankfully the yawn

stays inside. Unfortunately, what comes out instead is a burp. A loud one.

As though I’m drunk. (I’m not. I’m a lot of unpleasant things in this moment,

but drunk isn’t one of them.)

Because of the burp, my mouth starts to pop open again. I squeeze my

lips together so hard that my eyes begin to tear.

Of course, John doesn’t seem to notice. He’s still going on about Margo.

Margo did this. Margo did that. I said this. She said that. So then I said —

During my training, a supervisor once told me, “There’s something likable

in everyone,” and to my great surprise, I found that she was right. It’s

impossible to get to know people deeply and not come to like them. We

should take the world’s enemies, get them in a room to share their histories

and formative experiences, their fears and their struggles, and global adversaries

would suddenly get along. I’ve found something likable in literally

everyone I’ve seen as a therapist, including the guy who attempted murder.

(Beneath his rage, he turned out to be a real sweetheart.)

I didn’t even mind the week before, at our first session, when John explained

that he’d come to me because I was a “nobody” here in Los Angeles,

which meant that he wouldn’t run into any of his television-industry

colleagues when coming for treatment. (His colleagues, he suspected, went

to “well-known, experienced therapists.”) I simply tagged that for future

use, when he’d be more open to engaging with me. Nor did I flinch at the

end of that session when he handed me a wad of cash and explained that

he preferred to pay this way because he didn’t want his wife to know he

was seeing a therapist.

“You’ll be like my mistress,” he’d suggested. “Or, actually, more like my

hooker. No offense, but you’re not the kind of woman I’d choose as a mistress

. . . if you know what I mean.”

I didn’t know what he meant (someone blonder? Younger? With whiter, more sparkly teeth?), but I figured that this comment was just one of John’s

defenses against getting close to anybody or acknowledging his need for

another human being.

“Ha-ha, my hooker!” he said, pausing at the door. “I’ll just come here

each week, release all my pent-up frustration, and nobody has to know!

Isn’t that funny?”

Oh, yeah, I wanted to say, super-funny.

Still, as I heard him laugh his way down the hall, I felt confident that

I could grow to like John. Underneath his off-putting presentation, something

likable — even beautiful — was sure to emerge.

But that was last week.

Today he just seems like an asshole. An asshole with spectacular teeth.

Have compassion, have compassion, have compassion. I repeat my silent

mantra then refocus on John.

Excerpted from MAYBE YOU SHOULD TALK TO SOMEONE: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed by Lori Gottlieb. Copyright © 2019 by Lori Gottlieb. Published and reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on April 05, 2019.

This segment aired on April 5, 2019.