Advertisement

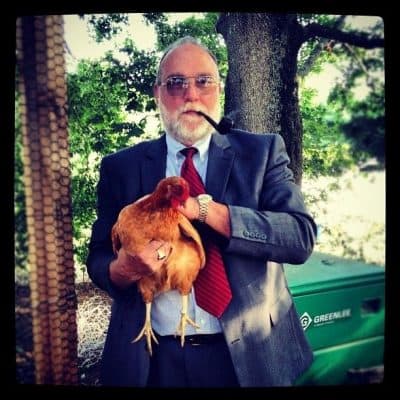

This Vietnam Vet From Brockton 'Just Didn't Like A Bully'

ResumeGreg Offringa talked fluently, with zest, on almost any topic: fixing a garage door opener, single-malt scotch, Buddhism. But unlike talkers who care most for their own company, he was also fluent at listening. People wanted to talk to him.

Any form of prejudice went against his bones. Greg was that way growing up in Brockton, where he became the de facto bodyguard for a vulnerable best friend. And he was that way when he volunteered at 18 years old to enlist in the Vietnam War. Communists, as he saw them, represented the worst of prejudice and persecution.

He explained it simply to his wife, Barbara Offringa.

"He just didn’t like a bully," Barbara said. "Never did."

Greg remained a committed humanist after returning from a tour as a helicopter gunner, but trauma had unnerved him. Long before the diagnosis became familiar, he struggled with nightmares and sky-high blood pressure. Rotting smells repulsed him. And for the rest of his life, he faced outwards in restaurants.

But his fluency for talking and listening hadn’t disappeared — nor had his belief in the goodness of people. This led to Greg's next career: clinical psychologist, treating others with trauma. Mostly he saw vets. Those from Vietnam had returned to a hostile, uncomprehending homeland, and Greg countered the judgment they met with absolute acceptance.

"You were fighting, a), to stay alive, and, b), to help the person next to you stay alive," Barbara explained. "There’s a camaraderie I don’t think you can understand unless you’ve been there."

In camaraderie, Greg once rode his motorcycle cross-country for a Disabled American Veterans fundraiser. But he didn’t tell Barbara many stories about combat.

"He told me, 'If our son is going to volunteer, it would be over his dead body,' " Barbara said. "He would not let our son go near anything militaristic, and that included the Boy Scouts."

The joys of life as a civilian took over: raising two children with Barbara, a monthly poker game that stretched over 30 years, making friends on the commuter rail to Boston.

But the war followed him. Growths in his larynx from Agent Orange required multiple surgeries. Eventually, his vocal cords were so damaged he had to buy a microphone to be understood by one hard-of-hearing patient.

The war followed him in another way, too.

"When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer," Barbara said. "We were driving home after the diagnosis and he said to me, 'I think I’m gonna just face this cancer the way I faced combat: you go in, you do your job, you don’t think about whether you’re gonna die or live, you just do your job.' "

Chemotherapy was just the job. The people in his life were the purpose. It was as if, during his time in combat, he hadn’t expected to survive long enough to find them. When he did, he wasn’t about to let them go.

To suggest a loved one for remembrance, email remember@wbur.org.

This segment aired on August 17, 2016.