Advertisement

With Homeless Shelters Already Full, Boston And State Collaborate On Winter Plan

Resume

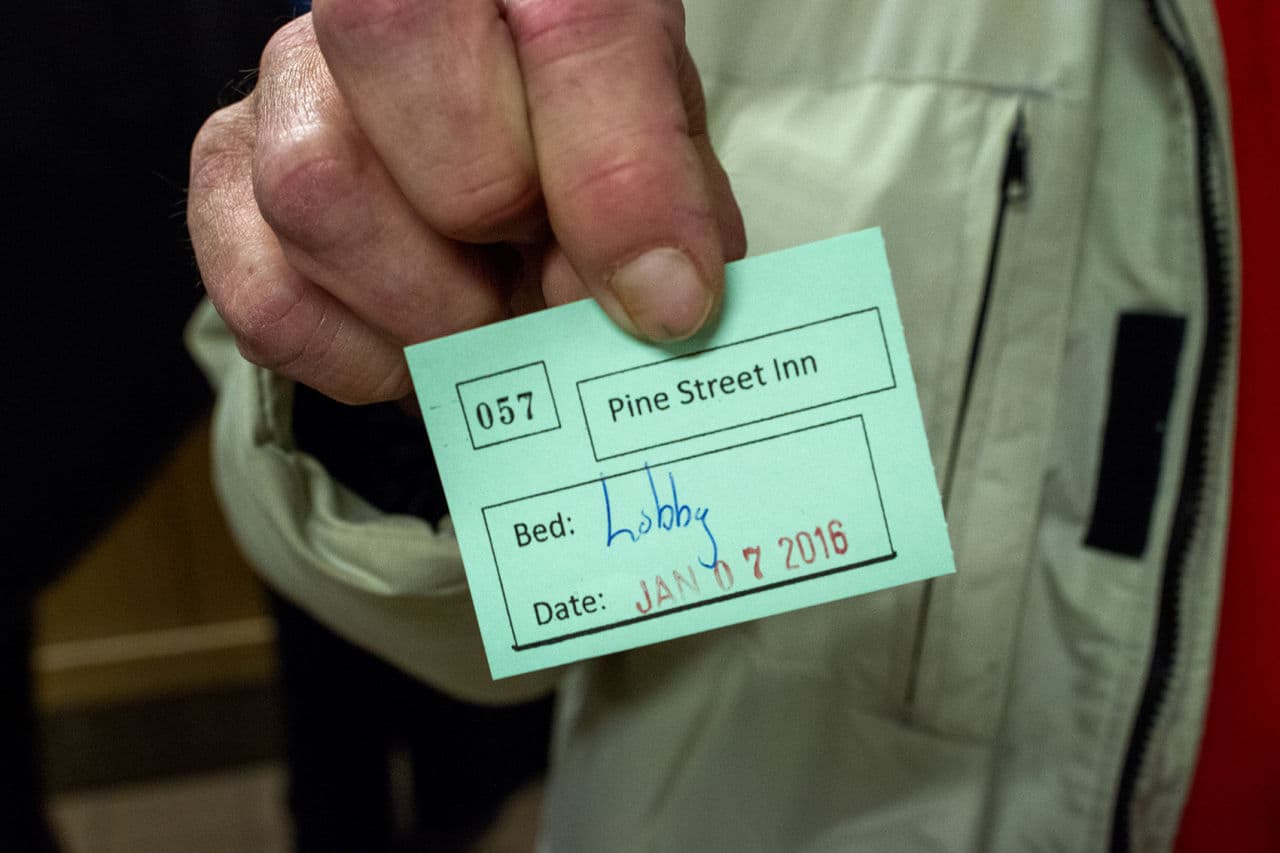

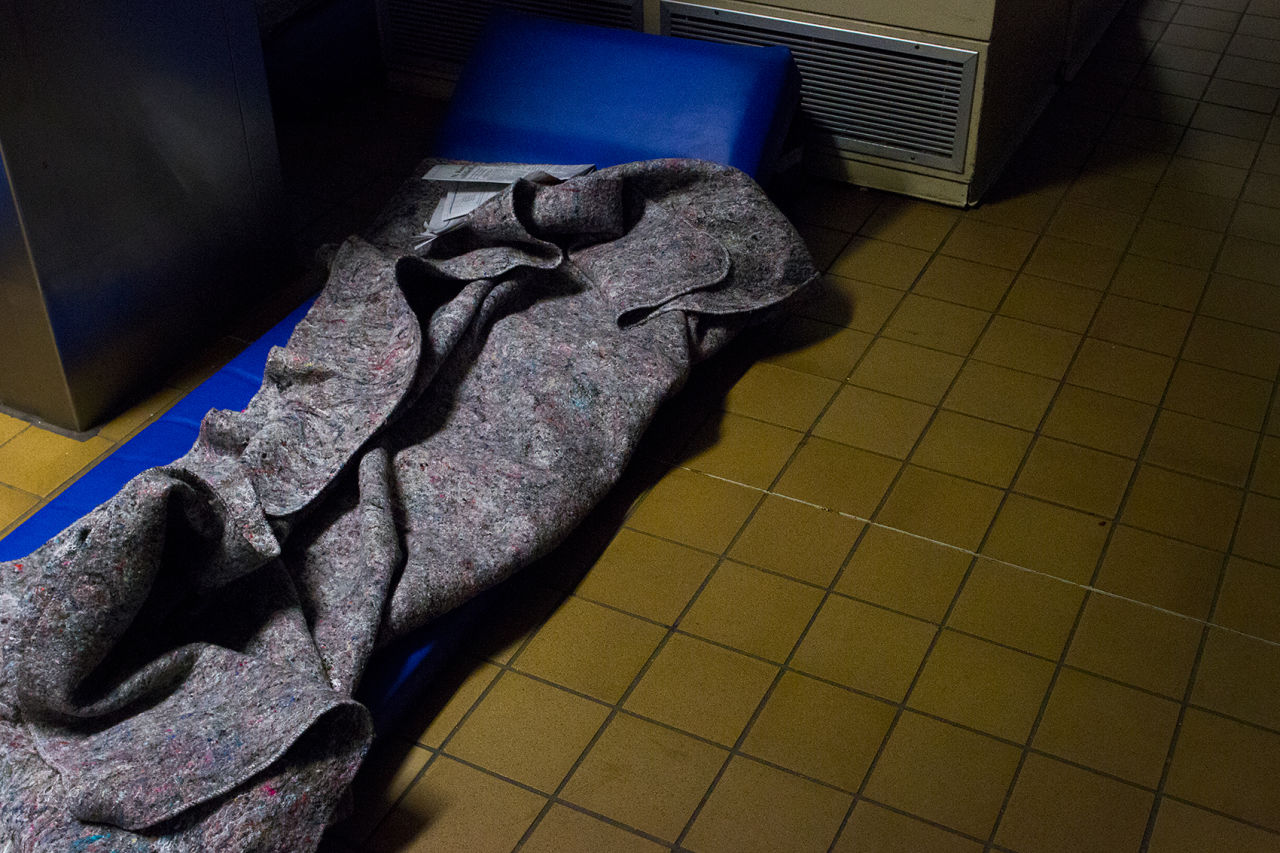

It's 9:30 p.m. The weather has been warmer than usual, but on this night Boston is expecting a freeze. All 390 beds in Pine Street Inn's towering shelter were full by 5. Staff have distributed 87 passes for the lobby, where up to 100 men can roll out blue padded 25-inch-wide mats.

But first, members of the 3-to-11 shift will turn off TVs in the lobby, shut down card games, and persuade tired souls to move into the hall so staff can fold up tables and store away chairs.

"Guys, go, everyone into the cafe until we clean up the lobby, just hang out in the cafe for a few minutes," shouts case manager Naomi Ramos, waving both arms toward a hallway.

Ramos and colleagues sort the men into two groups: those who’ve secured a lobby pass and those who'd rather go to St. Francis House, a day program that started staying open for the overflow from Pine Street Inn just last week. There are no beds at St. Francis but there is more space.

“I prefer to be right here in the lobby,” says Richard, who doesn’t want to give his last name. He’s a 74-year-old former Boston public school teacher who walks with a cane. “If there’s a fire, with the cane and the smoke — no, I’m very nervous and panicky about that, so this is where I prefer to be.”

Eight men line up to wait for a van. This system, of shuttling men about a mile from Pine Street Inn to St. Francis House, is part of a three-month, $1.1 million winter plan created by the city of Boston and the Baker administration to cope with shelter overcrowding.

Baker’s secretary for health and human services, Marylou Sudders, says demand for shelter has been increasing since the late summer.

[sidebar title="Winter Plan: Draft Summary Of 3-Month Funding Needs" width="300" align="left"]

For 18- To 24-Year-Olds:

- Bridge Over Troubled Waters: $250,000

For The Chronically Homeless:

- Boston shelter capacity: $627,000

- Capacity elsewhere in Mass.: $307,000

[/sidebar]

"We don’t know exactly why, but there seem to be two cohorts of the fastest growing individuals," Sudders says. "One is the 18- to 24-year-olds. We do believe that is absolutely tied to opioid epidemic in the commonwealth. And then there’s a group of 50- to 60-year-olds who seem to have had some connection to criminal justice, but we really need to understand that more."

The state and the city of Boston are sharing the expense of creating room for about 250 people -- about half in Boston and half elsewhere -- at a cost of $20 per person per night. The winter plan includes 24 detox beds to help patients move into treatment, and relieve some of the pressure on shelters.

The expanded shelter space is in Boston and in communities across the state, including Worcester, Haverhill, Lawrence, Quincy and several towns in western Massachusetts. Sudders says the state is trying to "mitigate the impact [of rising homeless numbers] on Boston."

The city's housing chief, Sheila Dillon, says about 40 percent of the men and women in Boston shelters are from outside the city.

"They’re coming for medical resources, social services, help with drug and alcohol addictions and housing. While we want to help everyone who arrives, Boston just doesn’t have endless amount of resources," she says.

Dillon and Sudders say they will make sure there is shelter for everyone who needs it this winter, but they are looking beyond the winter as well.

Dillon says Boston expects construction to begin on more than 1,000 new affordable housing units this year, and she’s hopeful that the city’s increased affordability requirement for new developments will add still more apartments for low-income residents.

"Really, our eye is on housing for people [who] have been in shelter for long periods of time and getting shelter to act more like emergency shelter, like it used to," Dillon says.

"You have to be committed to ending homelessness, that’s got to be the goal," Sudders says.

Sudders calls the working relationship the state is building with Dillon and city's housing team unprecedented. It's part of a larger winter planning collaboration between members of Gov. Charlie Baker's cabinet and Boston Mayor Marty Walsh’s top managers who met in late December to discuss transportation, social services and emergency response.

Shelter directors are encouraged, but still worried.

At Pine Street Inn, director Lyndia Downie says winter demand is up more than 20 percent in two years, and her guests are getting older and sicker.

"We’ve left the people with the fewest resources and the least ability to deal with it, we’ve left them to their own devices on the streets and in some cases in shelter," Downie says. "We've got it backwards. We should be giving those people maximum support and trying to get them stable."

And across the state, men and women are staying longer in shelters, becoming what’s known as chronically homeless. A survey from the Massachusetts Housing and Shelter Alliance found that 85 percent of these people have a persistent mental health problem.

MHSA director Joe Finn says the longer-term guests are using shelters are permanent housing. “Because of the inability to move people out of the existing shelter system, now we’re starting to see the crush in demand."

The Pine Street Inn's Downie says she has a proven model for moving disabled, long term homeless men and women into small units, with support so they can be stable. But she’s out of money to expand it.

So for now, Pine Street Inn is stepping up efforts to keep people out of shelter by helping people pay for a professional license so they can get a job, buy a bus ticket so they can go stay with family members, or make a deposit on an apartment. Anything to avoid the last-ditch option if the winter plan doesn't work -- opening a state office building so people can at least sleep on a warm floor.

This segment aired on January 12, 2016.