Advertisement

Cambridge 'Innovation School' Teaches Hands-On Creativity With A Twist Of Social Justice

In Cambridge's Central Square, there's a school of sorts where the tools of the classroom aren't textbooks or iPads.

Students are using laser cutters, sewing machines, drills, soldering irons, 3-D printers and good old-fashioned scissors and glue.

The place is called NuVu Studio. It's big and bright with high ceilings, and it's busy. Its goal is to get kids out of traditional classrooms and stretch their brains through hands-on creation. Some of the things the students create are meant to help people deal with weighty problems, such as being homeless.

"The problem of homelessness is not just that someone doesn't have a home. ... For individuals, the problems are deep ... and the understanding of those issues, I think, has really helped to build some empathy with the students," says Rosa Weinberg, one of NuVu's instructors, or "coaches."

The people who run NuVu call it an innovation school. Middle school and high school students attend the program full-time for three or four months. Some are public school or home school students. Many come from private schools. A majority are from affluent homes.

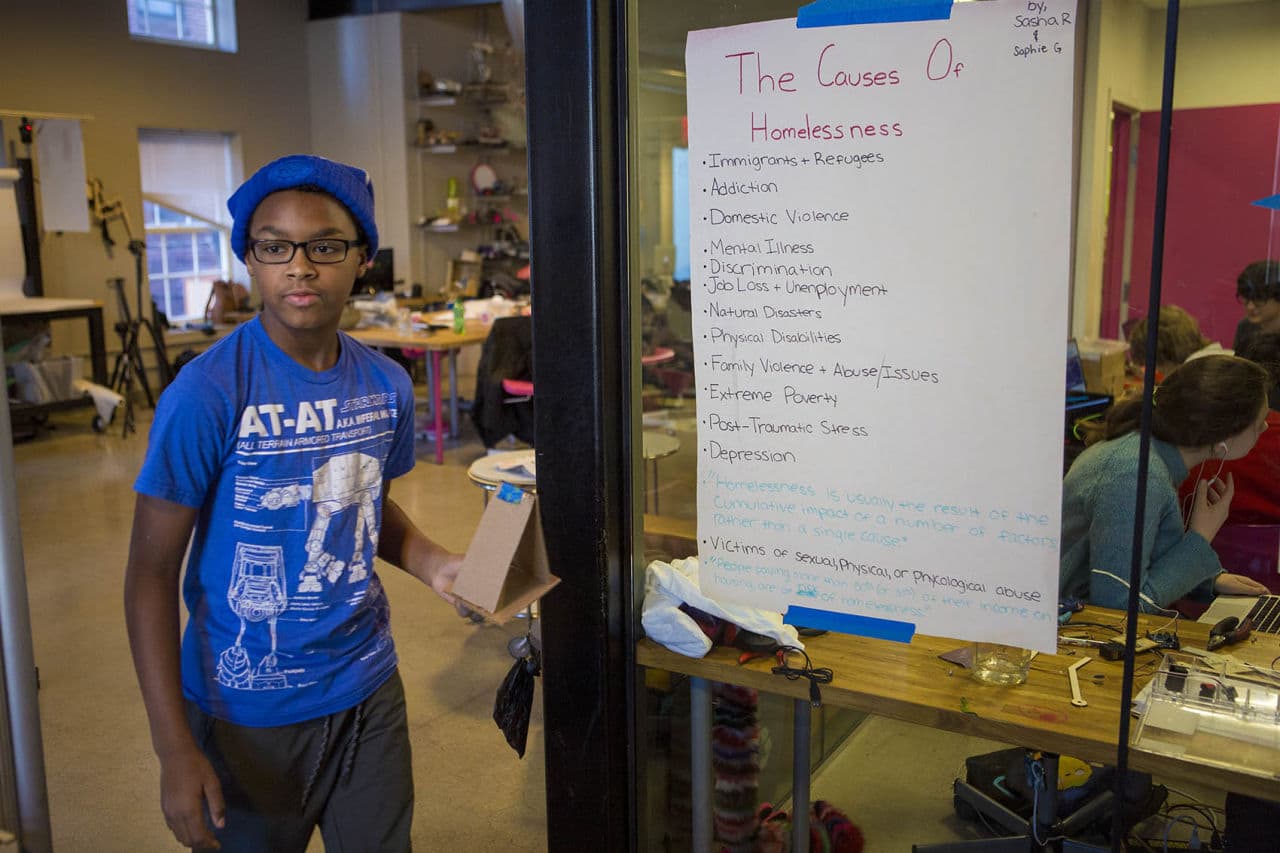

When we visit, the kids are about two-thirds of the way through their latest class, or studio. And this session is focused on homelessness. In just three weeks the kids have to research the issue and design objects that could help people who have no home. And they have to build the items, too. Students work individually or in small teams.

'We Want Them To Have An Open-Ended Problem'

Weinberg, a licensed architect, wants students to work through multiple iterations of their creations — just as in the architectural design process.

"We want them to have an open-ended problem," she says. "We want them to be in this slightly uncomfortable situation where they don't know what they're going to build, but they know what they want it to accomplish."

Aram Soultanian is 17. The table he's working at is covered with wires, glue sticks, plastic spools made on the 3-D printer and other supplies. Aram and his class partner, 17-year-old Noah Zakarian, are designing a portable cellphone charger from scratch.

They came up with the idea after their class went to see some homeless shelters in Cambridge. The kids discovered many people staying in the shelters have cellphones — and really need them.

"They have to call in [to the shelter] every day," Aram explains.

"They're on, like, a lottery system to get a bed for the night or however long they're staying there," Noah adds. "And they don't always have accessibility to charging their phones or other small handheld devices. I think it really shed a whole new light on homelessness for me, because it's really an aspect of homelessness that I didn't really see and I really learned so much."

The clip-on charger the boys are making harnesses kinetic energy from a person's footsteps or other movement. Inside the little box are several gears hooked up to an AC generator.

Advertisement

"So that's what creates the power when you step and when it's rotating," Aram says. "And then that's converted into DC power, which is required to charge phones."

Half of the 40 kids at NuVu are from Beaver Country Day School in Chestnut Hill -- NuVu's founding partner school. Tuition is steep, $13,000 a semester. NuVu does give some scholarships, and program leaders say they're hoping to expand the scholarship program to more schools.

Working Through Design Roadblocks

Some other recent studios at NuVu have focused on robotics and furniture making. In another, students designed and built prosthetics for musicians who are missing limbs.

In the homelessness studio, 19-year-old Alexia Duarte and her class partner, 18-year-old Simone Alexander, are adjusting a swath of black fabric across the torso of a mannequin.

"The problem is that there aren't many places for homeless people to sleep," Alexander says. "And what we're doing is we're making a wearable hammock for them to use."

The mock-up of the wearable hammock has shoulder pads made of cardboard.

"Basically the idea is to be able to have the hammock to come out of the shoulder pads, and they would be able to tie the top part of the hammock to the tree," Alexander explains.

It's actually kind of stylish by design. Alexander and Duarte want people who are homeless to get to wear something trendy.

Inevitably, students run into roadblocks — such as how to tuck all that hammock fabric inside the outfit.

On the day we visit, students are presenting the latest mock-ups of their projects to the group.

Steve Sterling is 11. He's making a massage tool to help people who live on the streets alleviate back pain. It features rotating balls and rollers that can be mounted to a pole near where homeless individuals sleep.

"They will move their back up and down or left and right, causing their backs to, like, smooth, to be smoothing out," Steve says as he explains the project to his classmates.

'More Invested And More Empathic'

There's a visitor on this day. Dr. Avik Chatterjee from Boston Health Care for the Homeless has come in to give the young designers feedback.

"This is a great project because one of the most common things we see in our clinic is pain, and joint pain and back pain in particular," Chatterjee says of Steve's massage tool. "And a lot of it has to do with the fact that people have to carry around all of their stuff, as you guys probably saw."

That kind of positive feedback, along with constructive criticism, help kids develop creative confidence, says NuVu's dean of students, Adam Steinberg, who co-"coached" the students in the homelessness studio.

"For me, what I hope for our students is that they feel that their ideas are valuable, whether they work or not, and that they have a sense of agency and accountability in the world that they live in when they leave here," Steinberg reflects. "If we can send students away from here feeling more invested and more empathic, then we've done our job."

In fact, in one of the next sessions at NuVu, students will be designing and building electronic devices meant to help people develop empathy for endangered animals.

This segment aired on March 10, 2016.