Advertisement

Japanese-American Sons Fought And Died In WWII As U.S. Detained Their Family

Monday is the official holiday that recognizes the men and women killed in the course of U.S. military service. But for a Medford mother and daughter, every day is Memorial Day. Summer and Miki Akimoto are committed to keeping the memory of their family's sacrifice during World War II from fading away.

Their sacrifice was unique to Japanese-American families. On December 7, 1941, everything changed — for America and for them. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor turned not only Japan into a U.S. enemy, but Japanese-Americans too — no matter how established they were here.

Raised To Be Americans

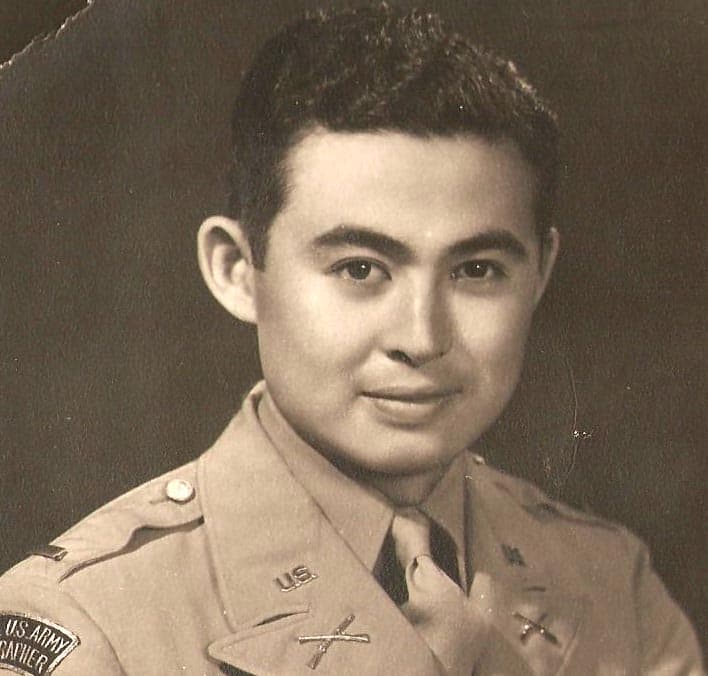

"Dad really always felt very American. His father in particular loved America. And the children were raised to be Americans," says 51-year-old Miki Akimoto. Her father was Ted Akimoto. "Dad was named after Theodore Roosevelt."

Miki and Summer, who is Caucasian, live in Medford. Summer and Ted were married for more than 50 years. Ted died five years ago.

Ted and his brothers and sisters were raised in Los Angeles. Their parents had immigrated from Japan, but the family lived a typical American life. Ted never even learned Japanese.

But when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor their lives were upended. Ted’s older brother, Victor, volunteered for military service the next day. His brothers would later join him.

"They felt it imperative to prove that they were loyal Americans — that this was an obligation that they had both to defend America, which was the country that they loved and that they belonged to, but also to prove that the Japanese-Americans could be trusted," Miki explains. "So it was really this dual purpose from the very beginning."

'Greeted By A Machine-Gun-Mounted Jeep'

After Victor signed up for the U.S. Army, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the army to round up tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans along the West Coast. The fear was that Japanese-Americans would collaborate with Japan.

The Akimotos were taken from their home.

"I remember Ted's remarking the horror of walking out, carrying only what they could carry including their bedding, to find them greeted by a machine-gun-mounted jeep, waiting, pointing the guns at them, waiting for them to get on the buses." recounts Ted's widow, Summer.

Advertisement

"I remember Ted's remarking the horror of walking out, carrying only what they could carry including their bedding, to find them greeted by a machine-gun-mounted jeep."

Summer Akimoto

The buses took Ted’s family to an "assembly center." It was actually a horse stable at a race track, a kind of holding pen.

"[The children] were all born in America, American citizens, and suddenly they were sleeping in horse stalls. Both of [their] parents were highly educated," Summer says.

The family had to clean the stables. The Akimotos then found work on a sugar beet farm in Idaho. That work was allowed because it was considered essential to the war effort. It was intense labor, and the family had to fend off anti-Japanese slurs and threats.

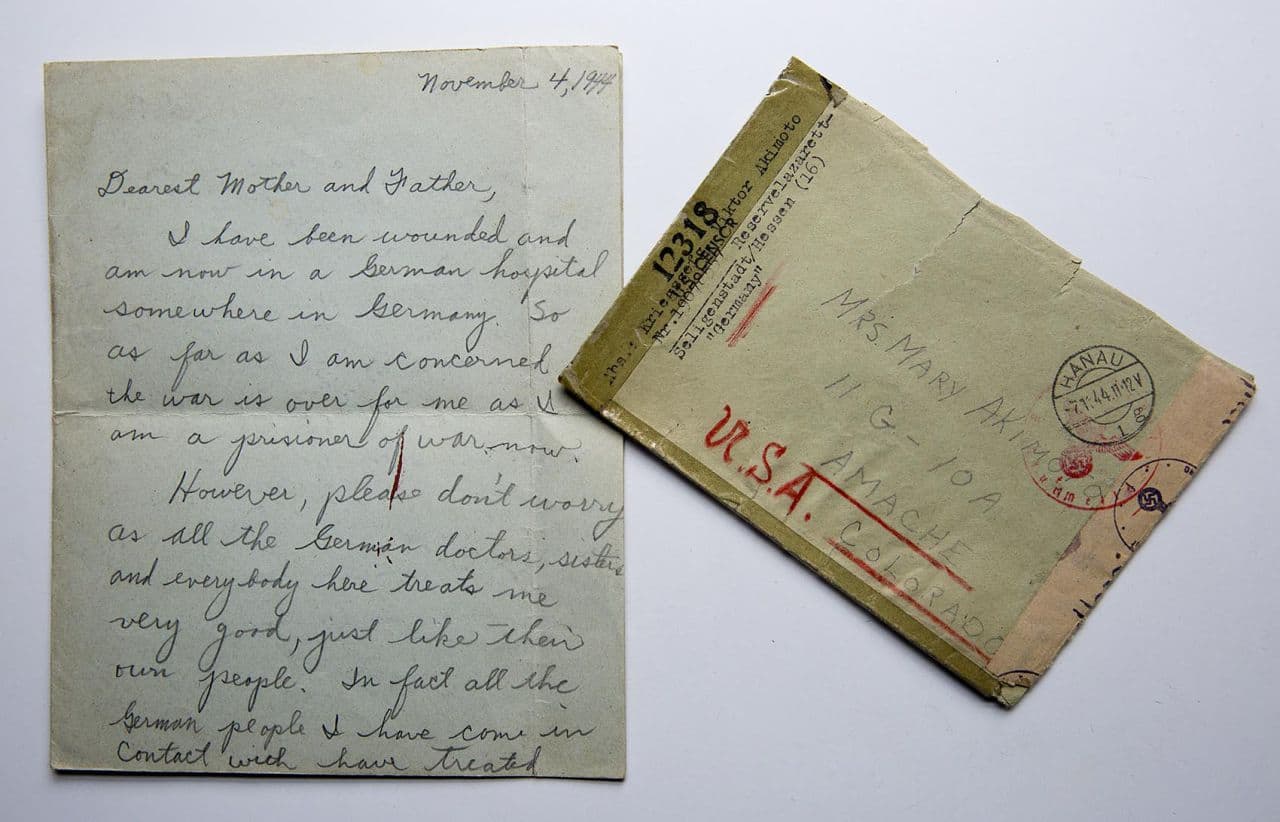

In mid-1943, the Akimoto family reported to the Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado, known commonly as Camp Amache. They’d become part of one of the most shameful chapters of U.S. history: the detainment of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans.

The family had no money, had lost their home and possessions, and had no choice.

The Akimotos described the camp as dusty, windy, desolate and very cold in winter. People were housed in long, drafty, tar-paper-covered wooden barracks.

Because Washington feared all things Japanese, young Japanese-Americans were barred from joining the military -- they were classified as enemy aliens. When the government reversed course, Ted and his younger brother Johnny volunteered for the Army.

The Sons Of Japanese Immigrants Defend America

The Akimoto boys became a part of U.S. history few Americans know: the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a military unit made up entirely of the children of Japanese immigrants who volunteered for service.

The three Akimoto brothers who fought for America in the 442nd had very different fates.

Johnny contracted hepatitis and died in Italy. Victor was shot in the leg while members of his all-Japanese unit rescued a unit from Texas, surrounded by German troops in the mountains of northern France.

"In the evacuation out, the group that Victor was in was captured by the Germans, so Victor ended up in a prisoner war camp of the Germans with this badly injured leg, which then became infected. He developed sepsis and ultimately the leg had to be amputated," Miki says.

The Akimoto family didn't know about Victor's shooting and amputation until a teacher named Matthew Elms researched and wrote a book for the American Battle Monuments Commission. It's called "When the Akimotos Went to War."

"The German camp records, which the researcher was able to locate, indicated that after Victor's leg was amputated he asked not to be fed any further, and that he died," Miki explains.

Before that, Victor wrote to his parents at the Colorado internment camp:

November 4, 1944

Dearest Mother And father,

I have been wounded and am now in a German hospital somewhere in Germany. So as far as I am concerned the war is over for me as I am a prisoner of war now.

However, please don't worry as all the German doctors, sisters and everybody here treats me very good, just like their own people ... Please give my love to everybody, for I certainly do miss you all.

God Bless you,

Victor

"For me, that letter is the great horrible irony and paradox of the 442nd, of these boys over there losing their lives while their parents were locked up," Miki reflects. "It's one of those stories that I'm afraid is dying out. I know that there are organizations that are trying to keep this story alive. But I find on the East Coast, anyway, so many people don't know about the 442nd, and sometimes don't even know about the Japanese-American internment."

The 442nd became the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in U.S. military history.

Miki's father Ted wanted to join his brothers fighting in Europe but never did. Victor had pleaded with the unit chaplain to see to it that Ted would be protected, and it worked. He remained stateside.

After the war, Ted was an official photographer for Gen. Douglas MacArthur. He was sent to Japan to document life there. He was one of the first people to photograph the devastation in Hiroshima. His photos are now part of military archives.

Ted went on to teach photography and art for 30 years at a high school on a U.S. military base in Germany.

Miki recalls how her father would speak in history classes at her school about the U.S. internment of Japanese-Americans. It was a part of U.S. history left out of history books at that time. In Massachusetts, state education guidelines call for the subject to be taught.

Never Bitter

Ted's widow Summer says despite the internment of and discrimination against Japanese-Americans, Ted and other Japanese families the couple knew were never bitter.

"Ted explained to me that their acceptance into general society had come much faster than it ever would for the African-Americans," Summer recalls. "He said it was a very hard passage, but we got here much faster and it will be a long time before African-Americans enjoy this degree of [acceptance], and right he was. I mean, he told me that 50 years ago."

The couple's daughter sometimes feels angry.

"I think what I am resentful about is that we do not seem capable of learning this lesson, that we are still creating classes of others," Miki says. "And one of the things that always struck me is right after 9/11, when it became clear that this was a terrorist attack originating in a Muslim country and Muslims were randomly targeted, the Japanese American Citizens League was one of the first groups to stand up and say, 'We must stop this. Haven't we learned this lesson?' And that this lesson continues to not be learned."

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which authorized reparations to surviving Japanese-Americans who had been interned by the U.S. during World War II.

Ted Akimoto and his wife Summer used that money to travel the world, before settling in Medford.

Before he died of a heart attack five years ago at the age of 89, Ted made clear he wanted to be buried in the Massachusetts National Cemetery, the armed forces cemetery in Bourne.

His brothers Victor and Johnny are buried side by side in a U.S. military cemetery in France.

Miki Akimoto says her generation of the family has taken on the duty of ensuring that on important dates throughout the year, there are flowers placed at each of those graves.

The music used at the end of the audio version of this story is "Go for Broke," composed by Jake Shimabukuro. "Go for Broke" was the motto of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

This segment aired on May 27, 2016.