Advertisement

‘A Safe Space’: Therapy, Support Groups Help Those Grieving After Homicide

Resume

For one family in Boston, one date — June 8 — may always bring pain. That's the date 17-year-old Raekwon Brown was fatally shot last week outside his high school in Dorchester.

Family and friends gathered Thursday for Raekwon's funeral.

Those who mourn a death by homicide endure a particular kind of grief — with its own burdens and emotional scars.

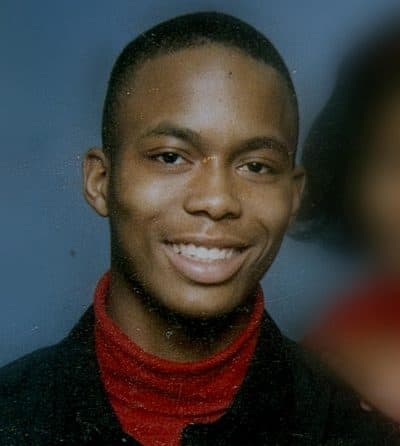

Cassandra Worrell is one of them. Her son, Anthony Worrell, was murdered on Aug. 31, 2011, in Charlestown. The 28-year-old was shot once in the torso. His mother says she still feels her own wound from the grief.

"You don't have the closure, where if he was ill, I could have spent time and let him know how much he meant to me and loved me, and I loved him," Worrell says. "It's just, 'Bam!' Your son is dead. And what you do is you go and view the body, and you can say there, 'I love you.' It's not the same."

"Tony" was a young man full of joy, who loved to make her laugh, Worrell says. He liked computers and kids. But his mother learned quickly that not everyone wanted to hear her talk about his death.

"I was feeling, like, withdrawn and alone," she recalls.

The violence of her son's death — and the depth of her pain — made people pull back. She says efforts to talk about him were met with silence or a simple, "I understand."

So she found something that helps. She meets weekly with social worker Cynthia Kennedy, who specializes in treating people grieving after a homicide. Kennedy is clinical coordinator of the Homicide Support Services Project at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

"So often people feel like they have to take care of others when they talk about a loss due to homicide — take care of other people's reactions or feelings — because it can be stigmatizing," Kennedy explains. "Having a safe space, they don't have to worry about anyone else's reaction, they don't have to worry about taking care of anybody else. They can just bring what they need to bring."

Sometimes they bring emotions that are foreign and frightening.

"Intense rage, or intense anger, desire for revenge," Kennedy says. "People can often experience post-traumatic stress reactions. They could have nightmares, they could have increased fear or hyper-vigilance."

The talk therapy helps people tamp down those reactions. Kennedy also teaches them techniques such as guided meditation and breathing exercises to give the mind a rest.

Finding Solace Through Shared Grief

A few miles away from Beth Israel, grief from homicide is dealt with in a different way — through peer support. People gather at the public library in Dorchester's Grove Hall neighborhood to talk, pray and sing.

Janet Connors leads the gathering, called a "peace circle." It's organized by the group Legacy Lives On. Most of the dozen people who've shown up here on a Saturday afternoon lost a son to homicide. That includes Connors. Another woman's grandson was murdered.

The participants sit in a circle. They take turns talking about their highs and lows from the week. And they talk about principles of peace, such as unity, love and justice.

There's a lot of talk here of anniversaries — but not the happy kind.

"I've been feeling down, because my son's anniversary is coming in July and it usually starts hitting me in May," says Ramona Jones, whose son, Anthony Weeks, was shot to death in 2002 when he was 16. "All I want to do is sleep now. That's all I want to do. It's hard for me to get out of the bed."

But she does, and she finds ways to cope.

"I buy coloring books and I just sit and color," Jones tells the group. "I use the colors that Anthony liked. He liked blue and black. And I just sit there, and I just say, 'Anthony, I'm coloring this for you.' "

Leean Taylor is mourning her son Daniel. He was murdered in 2014 at the age of 23.

"When I'm feeling down I light a candle and I talk to him, and the aroma from the candle makes me feel like he's with me," Taylor says.

It's music that brings Charmise Galloway closer to her son Da-Keem. He was murdered when he was 14, in 2004.

"When I think of my Da-Keem, I have all his favorite artists on my iPod, so I'll be probably rapping to 50 Cent or a whole lot of Nelly," Galloway shares. "God, he loved Nelly."

The nine other women and two men respond with yeses and laughter. That lightens the shared pain.

The people here say the group's a lifeline. When they're not meeting, they're texting or messaging each other. Seraphina Taylor is approaching the 15th anniversary of her son Carl's murder.

"When I say that my heart beats every day for every last one of you, even if I don't call you, I go on Facebook," an emotional Taylor says. "My kids say to me, 'Don't do Facebook, Mom, because it hurts you. You're always taking on someone else's pain.' "

There is no escaping grief.

Lola Alexander still calls herself a mother of six. "I only have three left now," she says.

She lost a daughter to brain cancer. A decade later, one of her sons was murdered, in June 2001. A couple months later, so was another son.

"Every time somebody else's child gets murdered on the street, we ball up in positions like [a] fetus. It hurts! We don't even have to know them. They're just a part of us," Alexander says. "We are here to build a format for those that are coming behind us. We got to strengthen ourselves. But this pain for murder, it'll never leave."

For some people, the image of what their loved ones' final moments might have been like never leaves.

Worrell, who's getting counseling at Beth Israel, says the pain is compounded because no one's been arrested in the killing of her son, Tony. And she says detectives haven't been in touch for a few years. So she's perpetually wondering what happened.

Social worker Kennedy says it can become like a mental movie.

"So your mind can just play and replay the scenarios, both in dreams and during the daytime, over and over, as you try to grapple with and make sense of this tragic loss," she says.

It's a lifelong process. Kennedy doesn't like to use words such as "closure." She talks about people reengaging with life.

Worrell is doing that. She left her job as a daycare administrator after her son's death. But she later started her own cleaning company, a job that gives her flexibility to take days off and go visit family out of state. That gives her a measure of peace.

"What keeps me going is that knowing that Tony wouldn't want me to be curled up somewhere, sad. So that keeps me going. That fuels my day," she reflects. "And I won't allow the perpetrator to steal my whole life. He might have taken my child, but he can't have me."

Beth Israel's homicide bereavement therapy is free to any survivor of homicide loss. It's part of the hospital's Center for Violence Prevention and Recovery, and it's a collaboration with the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute in Dorchester. The program is funded by grants from the Massachusetts Office of Victim Assistance.

This segment aired on June 16, 2016.