Advertisement

Through Grief, Children Of 9/11 Victims Gained 'Strength And Life Perspective'

More than 3,000 children lost a parent in the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Most of the children are adults now. But some were so young back then they have little or no memory of the parent they lost.

Jackson Fyfe is 16 now. He still feels the loss of his father. Relief from the grief comes in the form of a big hunk of clay.

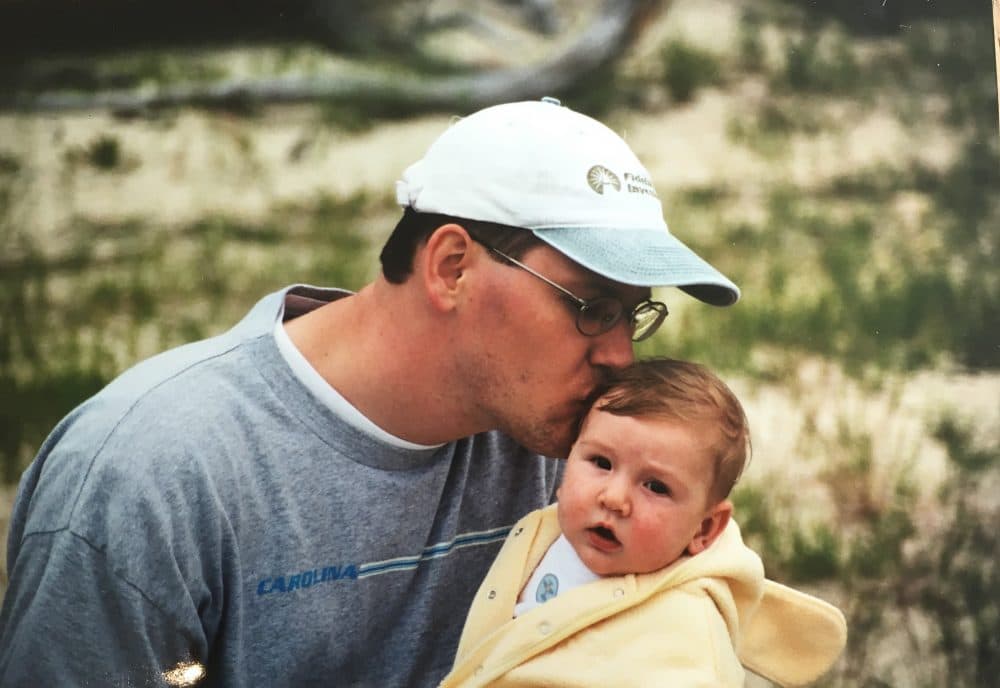

Words haven't always come easily for Jackson — especially words about his dad. Karleton Fyfe was a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11 out of Logan Airport. That was the first flight terrorists flew into the World Trade Center. Jackson was 18 months old.

Now he's a junior at Newton South High School. We met him in his favorite place: in front of a pottery wheel in the school's art room, where he started making a vase.

"I like the fact that I can take something from earth and I can turn it into a piece of art," Jackson said. Asked if there's a link between his loss on Sept. 11 and his art, he said it helps him deal with stress and anxiety.

"When you're on the wheel, you really can't think about anything else other than what you're making," he explained. "If you're sad or anxious or anything, you just tend to forget about it and you're able to channel your emotions into a piece of art."

'Fiery Feelings'

Jackson's mom, Haven Fyfe Kiernan, remembers how her son — even as a toddler — knew something was wrong on 9/11 and after.

"Because he was pre-verbal and didn't have any language to express how he was feeling about, 'Where's my dad? What happened to my dad? Why are you crying? Why are there so many people in the house?' it came out as behavior," Fyfe Kiernan recalled. "And it came out as a lot of tantrums, night terrors, inability to be left with strangers — so, overnight changes."

The day before her husband died on Flight 11, Fyfe Kiernan found out she was pregnant. When the baby was born, that meant even more adjustment for Jackson.

Grief is part of Fyfe Kiernan's professional life. She's a social worker, and even before 9/11 she specialized in grief and trauma after loss. Now she runs a counseling center in Newton, as well as expressive therapy programs that use music, dance, yoga and art.

For years she worried Jackson wasn't talking about his loss. He was depressed and anxious. Talk therapy wasn't his thing. But they found out creating art was.

Advertisement

"Jackson started with glass, which involves really hot fire, and he had a lot of fiery feelings growing up," Fyfe Kiernan said. "And the heat of the glass was a great way for him to channel into the fire of the emotions and then make something beautiful out of it."

Fyfe Kiernan has counseled several children of 9/11 victims, and she knows others socially through the 9/11 community. She says she's seen them thrive.

"It has been amazing to watch these kids grow up and flourish into unbelievable people, unbelievable adults," Fyfe Kiernan reflected. "And there is something to be said about having endured a trauma or a loss at an early age and really what that can manifest into — in terms of strengths and life perspective, and patience and creativity, and following a dream."

'Great Things Can Come Out Of It'

Eighteen-year-old Carly Gordenstein of Sudbury and 20-year-old Anna Sweeney, from Boxborough, are two of those young adults. Both lost their mothers, who were on American Airlines Flight 11 — the same flight as Jackson's father.

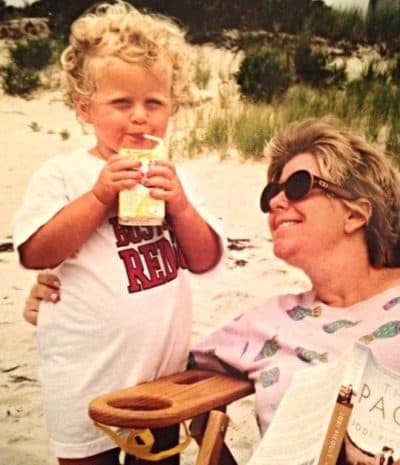

Anna's mother was flight attendant Madeline "Amy" Sweeney. She was one of the two crew members who calmly phoned airline workers on the ground to tell them about the men who forced their way into the cockpit to commandeer the plane.

Anna was 5 years old then.

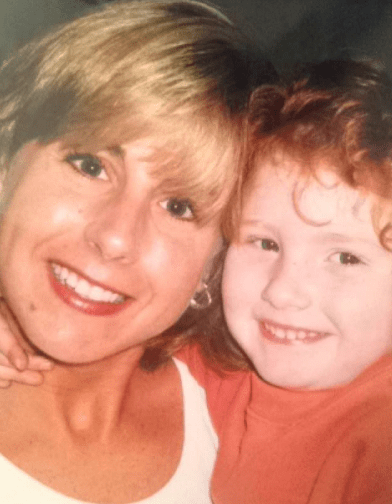

Carly's mother, Lisa Gordenstein, was a passenger on the jet. Carly was 3.

"I don't have many memories [of her]. I think I have, like, one," Carly said. "My mom used to travel to Hong Kong a lot for work. She came back with a giant cookie..."

Carly and Anna formed a bond as kids. They used to attend a camp for one week each summer in western Massachusetts. It was for children who had lost a parent on 9/11.

"It's just that weird feeling of you have so much pain and grief over someone that you can barely remember, and we kind of all have that same experience ... It's not like we have this lifetime of memories with this person," Carly said.

"I have memories, but obviously I was only 5, so they're not, like, very detailed memories," Anna said. "They're just short little things that I remember that I just, like, carry with me still. But obviously if I was older I'd be able to process that more, I think."

Carly adds that her "best friends in the world" are others who lost a parent on 9/11.

"Some of the best times that I've had are with them. And [there's] just that sense of great things can come out of it," she said.

We spoke with Carly and Anna at Anna's family home in Boxborough. They say in high school and before they felt bombarded by the images of 9/11, especially around the anniversary.

"So then you feel like you need to be thinking about it and talking about it, even if it's not what you want to be doing," Anna said.

They would talk about it in history and current events classes. Carly remembers the other kids would turn to look at her. She says it helps for her to think of the tragedy of 9/11 as one event, and the death of her mom as another.

"I try to view it a little bit more analytically or intellectually, rather than my mom dying," Carly explained. "I try to separate that from 9/11 — as in her life, and then the event that kind of ended it that was two minutes of her life. So it doesn't really register to me as emotional, as something else might."

As for Anna, for many years she didn't want to know exactly what happened to her mother on Flight 11.

There's an award for civilian bravery given in her mom's name every year at the State House, and Anna speaks at the ceremony.

It wasn't until Anna turned 12 or 13 that she started to read the old newspaper clippings.

"When I was talking to my dad about it a few years ago, and other people in my family, they said that what she did isn't out of character for who she was ... and just putting others before herself was just something she always did."

Carly says 9/11 has shaped her plans for what she wants to do with her life.

"I'm studying political science and Arabic, because I want to go into some sort of homeland security or counter-defense," she explained.

As she begins those studies at UMass Amherst, she says her personal loss on 9/11 has given her perspective.

"It's just kind of given me more empathy for other people who are going through the same things in different regions of the world," she said. "It kind of connects you in that way, and just gives me a stronger resolve to want to do something."

Carly even went to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in July with her father, to observe pre-trial proceedings for the men accused of plotting the 9/11 attack.

"I was staring at Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who's the mastermind of 9/11, and seeing them — they were laughing and talking with each other — it was a very strange experience."

Anna also hopes to get her chance to go and watch.

It's all part of the evolution. Carly's father remarried and she calls that woman mom.

"I've gained a great family — and it's never been a divided thing, in my mind, at least," she reflected.

Anna is starting her third year at Northeastern University. Like Carly, she's studying political science, along with criminal justice. And she has a sense of adventure. She likes to pick up and travel around the world — just like her mom, the flight attendant, did.

"It just made me a very independent person, and it's obviously shaped who I am now," Anna said of 9/11.

Letting Go And Starting Over

Jackson Fyfe has a dad now, too. His mom, Haven Fyfe Kiernan, got remarried to a man who adopted Jackson.

Jackson's pottery is his meditation and joy. He even sells his wares online. He says he likes seeing how his ceramics are an extension of what he's feeling.

"If my pieces come out really thick, that can be a time when I was shaking and anxious about something," Jackson said. "But other times being anxious is a good thing, because you can get cool patterns from your body shaking."

He dreams of having his own studio and gallery some day.

During our visit, he noticed the vase he was almost done working on had a gaping hole.

He laughed it off, kneaded it back into a glob of clay and calmly started fresh.

His mom says it's all part of letting go and starting over.

This segment aired on September 9, 2016.