Advertisement

Matthew Aucoin’s 'Crossing' Fails To Reach Its Potential, But Gets An A For Effort

There’s a compelling plot idea at the core of Matthew Aucoin’s "Crossing," which the American Repertory Theater just spent a million dollars developing for its world premiere at the Shubert Theatre (remaining performances June 2, 4, 5 and 6). Inspired by Walt Whitman’s Civil War diaries, the story is about the poet’s volunteering in a Union hospital. He wants to help nurse the wounded soldiers back to health or at least offer some comfort for those too weak to survive. But his worthy motives might be compromised by his sexual attraction to the young war victims. Along comes a wounded Confederate soldier in disguise, who detects Whitman’s attraction to him, sleeps with him (decorously, of course), and gets him to write for him a letter to his family which is really in code and could lead to the Confederate army destroying the hospital. Fortunately, the war ends before this catastrophe can take place. The soldier confronts Whitman and tests his capacity for universal love, then dies. Nice, tight story. Poignant, gripping, with a homoerotic twist. Could make a powerful short opera, like Puccini’s "Il tabarro," say, 40 minutes tops.

But this is only 25-year-old Aucoin’s second opera, and he evidently wanted to get as much meaning into it as he could. He crammed his libretto, which he wrote himself (he was an English major at Harvard, class of 2012), with unidiomatic diction, long quotations from Whitman and other poets, and even references to the "Divine Comedy." Extended oratorio-like choral passages stop the action for periodic injections of Significance. There’s even a flashback ballet — three soldiers lifting and twirling their long-haired girl back home — that seems right out of the dream ballet in "Carousel" (I don’t know if this idea was actually Aucoin’s or stage director Diane Paulus’s or choreographer Jill Johnson’s, but it was an embarrassment). Paulus couldn’t do much with such melodramatic touches in the libretto as the Confederate, John Wormley, telling Whitman “You’re sick" and calling him a pervert or turning to the audience to confess his villainy. (Or could she?)

So instead of a devastating short opera, we get an inflated one that goes on for nearly two hours without an intermission and its numerous climaxes during the long home stretch make it seem as if it were never going to end. The final chorus quotes Wallace Stevens: “Nothing is final. No man shall see the end,” and I was beginning to fear this might prove prophetic.

Aucoin has been described, perhaps too often for his own good, as a Wunderkind. I hope that for all his many gifts he doesn’t take this too seriously. He an assistant conductor at the Met, and as an apprentice with the Chicago Symphony he filled in for no less a luminary than the ailing Pierre Boulez. He was composer in residence at the Peabody Essex Museum and has opera commissions from the Met and Chicago Lyric Opera. A very busy young man. But I hope he is given time to grow. "Crossing" was the first music by him that I’ve heard, and I’m happy to report that he’s a dazzling orchestrator. The endlessly colorful score glints and sparkles and glows in the dark. Textures and rhythms are continuously metamorphosing. And as a conductor, especially with an orchestra as scintillating as the usually conductorless A Far Cry, he is capable of bringing out all these sonic nuances.

And yet the score seemed to have no personal profile. The writing for orchestra, just as most of the writing for voice, seemed generic, with obvious changes of mood from scene to scene. So here was this libretto, very literary, rather clumsy (“I am alone,” the Confederate soldier kept telling us as if we didn’t already know this and he couldn’t think of any other way to put it), but desperate to articulate ideas, combined with music that seemed to have no revealing ideas or character or dramatic necessity. Musical interludes used to build tension or suspense were almost invariably mimimalistic repetitions. It’s a cliché that has by now sifted down to TV shows. One aria, a kind of visionary folk song or spiritual (in rhymed quatrains) for an escaped slave who is now a Union soldier, was especially haunting, and one of the few places in the entire opera when a singer (here, the eloquent young bass-baritone Davone Tines, another Harvard grad) wasn’t belting at the top of his lungs.

Advertisement

Not that the singing wasn’t good. Baritone Rod Gilfrey was a strong and earnest yet vulnerable Whitman, tenor Alexander Lewis the seductive and sinister John Wormley (made up to look rather vampire-like), and the chorus included such stellar Boston-based artists as tenor Frank Kelley and baritone David Kravitz, who almost effortlessly seemed to make individuals out of the too generically conceived wounded.

There were some klutzy scene changes I wish Paulus had put more thought into, and I would rather not have seen the chorus lining up at the edge of the stage. Paulus undercut the powerful confrontation scene between Whitman and the dying Wormley near the end by placing them far apart on the stage and not looking at each other.

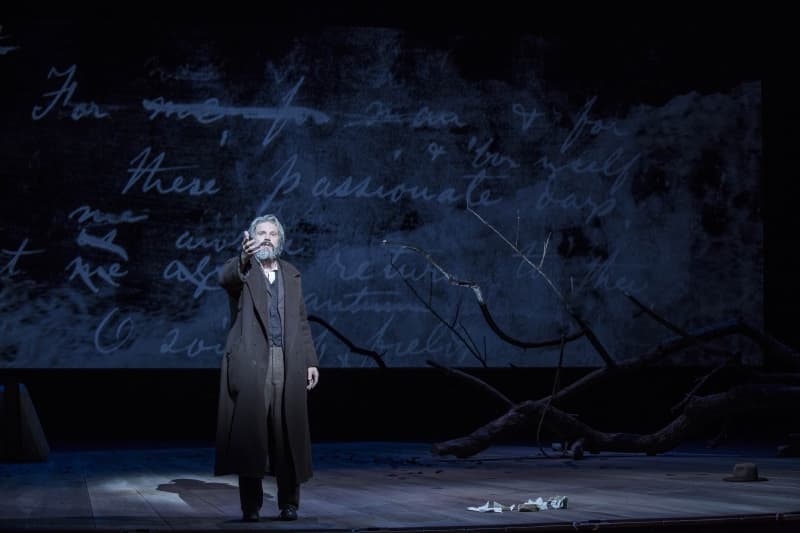

Tom Pye’s hospital room was appropriately spare and unrelievedly gray, with large walls for Finn Ross’s projections. A battlefield had a fallen tree. Jennifer Tipton, the celebrated lighting designer, created effective if obvious shifts in mood.

At the second performance, May 31 (Whitman’s birthday), the Shubert was just about full, and there was a warm ovation at the end. It’s good to see big money spent on a worthwhile project, though I didn’t think this one had achieved full maturity. I grew impatient and finally bored by its high-mindedness. I suspect that Aucoin is going to be subjected to a lot of comparisons with Nico Muhly, another successful young composer being cultivated by the Met, whose slick and implausible "Two Boys," with a sado-masochistic gay theme, was something of a hit in New York. But Aucoin has more on his side. I didn’t much like "Crossing," but it still makes me root for him to succeed.

Lloyd Schwartz is a music critic for NPR’s Fresh Air and Senior Editor of Classical Music for New York Arts. Longtime Classical Music Editor of The Boston Phoenix, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 1994. He is the Frederick S. Troy Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Follow him on Twitter @LloydSchwartz.