Advertisement

At The MIT List Center, 'Safe Passages' Takes Up The Theme Of Race, Power And Surveillance

In colonial America, “lantern laws” required that all slaves move about the streets at night bearing lit candles. The dancing flames served to track and control a population that might otherwise escape or rebel.

Today in the United States, we’ve dispensed with candles. Some would argue stop-and-frisk laws, racial profiling and overly aggressive police tactics are now the effective means of controlling people of color.

Paris-based artist Kapwani Kiwanga reflects on the history of surveillance and monitoring, and in particular racialized surveillance, in “Safe Passages,” on view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center through April 21.

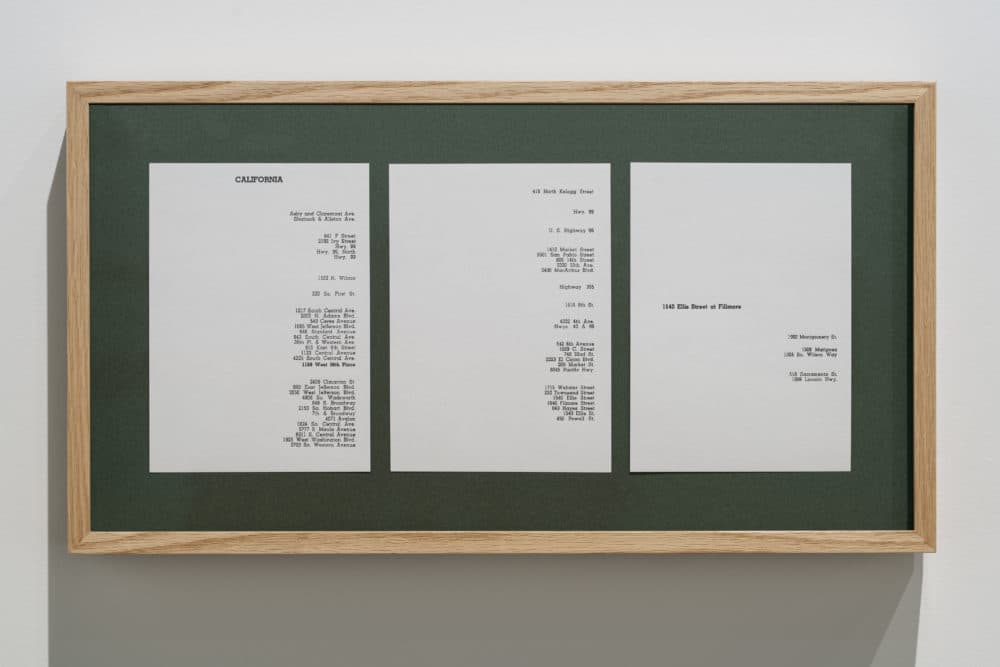

Walking through the show of cool and quiet objects, at first glance, you might think you’d been transported to an exhibit of minimalist sculpture by the likes of Dan Flavin, Donald Judd or Dan Graham. These are simple forms — four pillar-like objects, a mirrored screen, three partitions fashioned of a screen-like textile. In the back room there are a series of cryptic prints consisting of just addresses.

It's not what you might expect of an exhibit touching on such painful and provocative issues as race, colonialism and the lopsided dynamics between those with power and those without it.

One sculpture, entitled “Jalousie,” (2018), is simply a four-panel glass screen in which some segments are made of louvered glass (or jalousie) while other sections are solid glass. This glass, is not normal transparent glass, though. These panels are made of the two-way mirrors. As you move around the panels, you notice that sometimes you can see through to the other side and observe anyone who may be standing there. Other times, you can’t, although perhaps someone on the other side can see us.

“That piece is just so seductive,” says Yuri Stone, assistant curator at the List and organizer of the show. “It pulls you in and then you circumnavigate and slowly recognize the shift that happens in power dynamics from one side to the other.”

As with so much in life, what’s visible and invisible depends on where you stand.

Its angled slats recall the domestic windows and shutters found in homes all the way from the Caribbean up to New England. It is therefore a statement on the global aspect of shifting power dynamics. It is also a juxtaposition of technology. Slatted windows are a low-tech way of creating privacy while providing ventilation and the ability to observe. Mirrored glass found in police interrogation rooms, corporate observational rooms and on security cameras, is a higher-tech way of doing the same thing. Kiwanga says she intentionally linked “two different technologies that sprung from the same ethos or way of thinking or seeing, so that one can be hidden but also have this power to look on.”

And there is another level to this work, too. In adopting the language of minimalism, Kiwanga manages to fit her work into a historical context that both co-opts minimalism while simultaneously celebrating it.

“I think some people are so great at using maximal ways of working,” she says. “It's never been my way. I think there are lots of layers in my work, always. There's lots in it, but it's pared down.”

The group of sculptures, entitled “Glow” (2019) are those based specifically on the lantern laws that were first passed in New York in the 1700s and which were later adopted around New England. They feature four black forms covered in textured stucco with LED lights. On two of the forms, the lights are spherical, on two of the others, they are linear. Kiwanga keeps these shapes on a human scale, at the level at which a human might hold a lantern.

Also in the room is her piece “Tripartite” (2019), consisting of three partitions (technically four but two are welded together) created from shade cloth, an agricultural textile used in greenhouses and large-scale industrial farming around the world. The material can filter light to increase the yield of a crop according to environmental conditions. In Kiwanga’s piece, the material alludes to how agriculture has factored into colonization while also speaking to the specific action of filtering.

“It’s allowing light to come in, but it's also blocking out some of that, and of course that's what we're talking about, filtering people through surveillance,” she says.

Depending on where you stand in the room, the partitions also filter the light from “Glow” while the forms of “Tripartite” are reflected in “Jalousie.” Each form, therefore, is in dialogue with the other, providing a sort of continuum alluding to the passage of time.

In the second half of the exhibit, Kiwanga presents a suite of 21 prints, sourcing material from the 1961 issue of “The Traveler’s Green Book” (also the subject of the recent movie “Green Book”). The Green Book was the annual state-by-state listing printed from 1936 to 1966, listing restaurants, service stations, and lodging safe and open to African-Americans during the Jim Crow era. For this exhibit, Kiwanga chooses the 1961 edition with a specific intent --- that was the year a group of civil rights activists of mixed races rode interstate buses into the south to challenge segregation. “The Freedom Riders” were arrested for unlawful assembly and for violating state and local Jim Crow laws, but not before white mobs were allowed to viciously attack them as police stood by. It is Kiwanga’s poignant statement of how race has determined who has enjoyed freedom of movement in the U.S., and who hasn’t. By eliminating most of the text that appeared in the original version, we are left with only the state name and addresses, geographically dispersed from Maine to California. Laid bare, the prints illustrate simply and powerfully the pervasive nature of discrimination found in every corner of the United States.

The racism, discrimination and inequities that is so much a feature of American life is not limited to America, however.

“This is not just in the United States but all over the world in different degrees and different populations,” says Kiwanga. “The structures vary but they have similar underpinnings.”

The List exhibit is not Kiwanga’s first show in the United States, although it is her first in an American museum. In 2018, her piece “Shady,” an earlier rendition of “Tripartite,” was shown outdoors at Frieze New York. In 2017, she showed at the Logan Center at the University of Chicago. Although she is Canadian by birth, she is perhaps better known in Europe for pieces that can diverge in style but are always research-based and observation-oriented and which often deal with marginalized or forgotten histories.

Her work reflects her training in anthropology, comparative religion, and her background as a woman of color growing up in Ontario, Canada. It is, she says, informed by “being in the world myself and seeing other people in the world.” Her father is from Tanzania and as a child, she spent time in Africa. In Canada, she lived in close proximity to the Six Nations of the Grand River, the largest First Nation reserve in the country. Those experiences have given her the opportunity to examine, close-up, themes around colonialism, race and power.

“I think all my travels and places where I've lived have shown me that there's often power at play and that the power is asymmetrical.”

What’s important, however, is to not become mired in discussing inequities believing they can be found in just one place or time, says Kiwanga. Power imbalances happen everywhere, and they constantly shift. At one moment, an individual can hold power over others, and in the next, others can hold power over that individual.

“It's not excusing or trying to downplay the importance of a particular history,” she says. “But it’s trying to put it into conversation.”

“Safe Passages” is on view at the MIT List Center for the Visual Arts through April 21.