Advertisement

MASS MoCA Continues To Wear Many Hats As It Turns 20

Three exhibitions are opening at MASS MoCA this weekend: an experimental foray into installation art by singer Annie Lennox, a survey of artist and filmmaker Cauleen Smith’s work imagining black liberation, and a group exhibition of hot young artists whose title is taken from a Kanye West lyric (“Suffering from Realness”). There’s a talk by local historian and author Joe Manning highlighting the history, community and architectural setting in which the museum operates. A family-friendly block party with games like arty corn hole and a concert by NPR Tiny Desk Contest winners Tank and the Bangas will round out the schedule.

That’s how this world-class contemporary art museum located in the Western Massachusetts city of North Adams is celebrating its 20th anniversary.

The jam-packed schedule sheds light on how the institution sees itself: as a center of advanced art and performance by nationally and internationally known artists, an incubator of new talent and experimental ideas, and an institution that is very much part of a local community.

MASS MoCA is touted as the largest of its kind in the world, and boasts a total of 250,000 square feet of exhibition space. It was the brainchild of local business leaders and Thomas Krens, then-director of the Williams College Museum of Art who would go on to lead the Guggenheim Museum in its global expansion. A team led by one of Krens' acolytes, Joe Thompson, brought it into fruition. The original idea was to take a set of industrial buildings, recently vacated with the shuttering of the city’s largest employer, and turn it into an economic and cultural motor to drive the region toward prosperity.

The conception was not new, exactly. Before there was MASS MoCA, there was PS1 in Long Island City (now MoMA PS1), a school building repurposed as a contemporary art space. And since its founding, other spaces, inspired in part by MASS MoCA’s success, have been appearing on the national landscape, including the ICA Watershed in Boston, and the Momentary, a new venture in adaptive reuse by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

But MASS MoCA remains unique, according to Paul Ha, director of the List Visual Arts Center at MIT, for staying true to its roots. “I love the fact that even after 20 years, it's still not a standard ‘white cube’ experience. It still has that very much alternative space feel to it, sort of bootstrap.”

But its physical plant is not the only thing that makes it stand out. The fact that the museum has so much space at its disposal means that it’s been able to become something quite unique: namely, an incubator for the arts, a place where artists of all stripes could come not only to show work, but also to imagine and realize new projects and experiment with new ideas.

“I think the most impactful thing we've really done … is we have these residencies for people or artists who are in any stage from, ‘We're just coming in to think about something,’ to, ‘We're opening at the Next Wave next week, and we need the last tech rehearsal before we go on international tour,’ and kind of everywhere in between,” says Rachel Chanoff, curator of Performing Arts and Film at the museum.

This is precisely what brought William Kentridge, the celebrated South African artist, to the museum. In the fall of 2018 he worked with collaborators to develop a multimedia performance, “The Head & The Load,” that has gone on to tour worldwide. Jon Hamm, the actor most famous for his role as Don Draper in “Mad Men,” was also in residence this past spring to workshop a multidisciplinary project called “Fishing.”

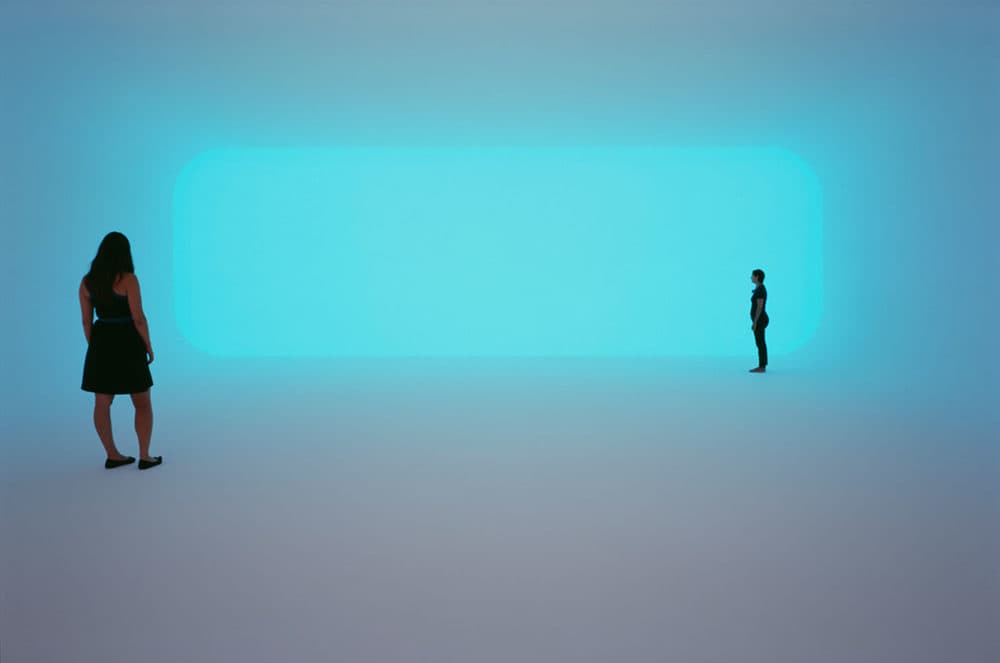

In addition to these residencies, a small number of artists, including James Turrell and Laurie Anderson, have been given space to use for long-term exhibitions of their work. And even for the rotating schedule of curated art shows, artists are encouraged to create new pieces on site.

Denise Markonish, senior curator and managing director of exhibitions at MASS MoCA, says that while bringing the best international artists working today to the museum is part of its core mission, it has the added benefit of bolstering a local arts community. “One of the best ways I've always thought of building a regional art scene is to put local artists in an international perspective, side by side with artists from elsewhere,” she says. Markonish notes that residents of the region including Mary Lum, Sarah Braman, Michael Oatman, Jeffrey Gibson and Mark Swanson have all found their way into the museum’s shows. The museum has also worked with local groups, such as the art collective Common Folk who launched a North Adams grassroots festival called O+ this past spring.

Markonish also draws attention to a museum-sponsored program, Assets for Artists, which is luring more and more creative types to move to North Adams with resources and incentives to live and work in the community. The program offers professional development workshops, capital grants, short-term artists residencies, and financial help to those interested in relocating.

At the same time, notes Michelle Daly — an artist and curator, and former director of the Berkshire Cultural Resource Center at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts — there is room for improvement in the museum’s outreach to local artists. She cites, as comparison, the increasingly common practice of contemporary museums curating shows focused specifically on local artists. These include big city institutions like the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis, and also those in smaller communities, such as the Portland Art Museum and Lincoln's deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum.

While Markonish sees a much greater diversity among the visitors in recent years as programming has changed to include black, indigenous and other artists of color in both visual and performing arts, my own frequent visits to the galleries suggest that it still skews very white. It also skews affluent, hip and mostly from far away — only about 30% of the museum’s visitors come from within 75 miles of the museum, with the rest traveling from New York, Boston, and internationally, according to the museum’s director of communications, Jodi Joseph.

The dissonance between who visits the museum and the local community, past and present, is not lost on those looking at the cultural impact of MASS MoCA on the region. Maurice Berger, research professor at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, and a part-time resident of the Hudson Valley, notes: “With each visit to its campus, I am struck by how little it reflects the story of the printers, electrical and mill workers and other working class people who constituted an important part of the area's history and present. Like so many projects like this, ‘high art’ serves an excuse and a justification for gentrification, and its resulting influx of affluent and largely white constituents. I wish I felt more of the actual constituent communities of Western Massachusetts and far less of the ‘art world’ in the museum's programming and sensibilities.”

Allana Clarke, an artist who moved to North Adams from New York recently to take a position as visiting lecturer in art at Williams College, also worries about the specter of gentrification that seems to accompany so many cultural development efforts. While MASS MoCA has been a major part of her artistic life since moving here, and has allowed her to see art and interact with artists in ways that she was able to do in larger cities, she notes that the museum admission price of $20 means that most local residents simply cannot afford to go. (The museum offers few occasional free admission days, citing its small endowment and high operating costs as a reason on its website FAQ.)

When asked about the question of gentrification, MASS MoCA director Joe Thompson demurs, noting, “Real estate prices, happily, remain quite affordable in North Adams (and a fraction of the cost of many other towns in the Berkshires). In short, we are still a long, long ways from any real ‘gentrification’ worries.”

Still, the museum’s impact on the cultural landscape has been undeniable, says Daly. “It’s probably fair to say I moved to North Adams because of MASS MoCA. … At the same time, I think that there are ways, now that they are established, that they can think differently about how they relate to specifically to the creative community.” She hopes to see engagement that matches the museum’s well-regarded outreach to children, school groups and the general public.

The painter Josephine Halvorson, a recent transplant to southern Berkshire County who teaches art at Boston University and had work in the recent MASS MoCA exhibition “Lure of the Dark,” sees other ways to measure the success of the institution, which she regards as an immensely valuable presence.

“I think it gives residents, friends of mine who are not in the various art worlds, who live locally, a sense of pride in the area as well," she says. "It is a world-renowned institution. And people come from far and wide to go to MASS MoCA. It makes you feel connected to the world.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated when Dia:Beacon opened. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on May 24, 2019.