Advertisement

This Book Makes The Case For Boston's Place In Counterculture History

In 1968, hippies gathered on Boston Common to spread their message of peace and love. This romanticized, simplistic image is frequently associated with counterculture, but looking beyond the dreamy and hazy veneer, there was a lot of unrest and invention bubbling beneath the surface. People read alternative weekly newspapers; listened to emerging bands on WBCN; went out to folk, jazz, punk and rock shows; and fought for civil rights.

This counterculture wasn’t exclusive in Boston. Driven largely by young people, it was transformative and widely embraced. It defined the city’s entertainment and politics. It paved the path for gonzo journalism, album-oriented programming, and bands like The Cars.

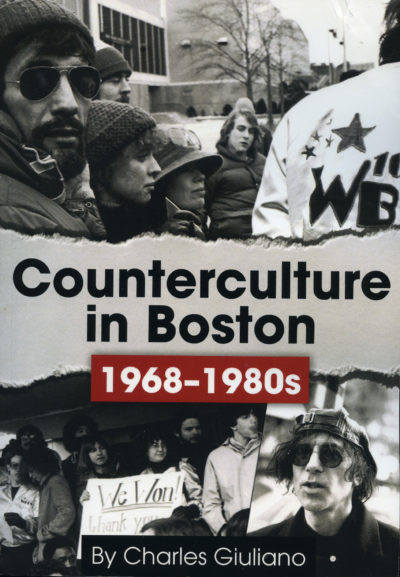

Charles Giuliano, a journalist who covered music for Boston Herald Traveler and alt-weekly newspapers, was on the frontlines of the local counterculture that began with hippies gathering on Boston Common in 1968 and sold out by the 1980s. He watched Boston’s counterculture unfold through the lens of his film camera, seeing bands like The Rolling Stones and The Grateful Dead, frequenting jazz clubs, hanging out with Miles Davis, and becoming acquainted with Fort Hill Community cult leader Mel Lyman. His new book “Counterculture in Boston: 1968–1980s” makes a case for Boston’s cultural revolution that impacted the nation during an idyllic but restless moment in time. The story is told through interviews with key figures in the scene and photos from Giuliano and the late Peter Simon and Jeff Albertson.

Giuliano’s book comes shortly after Bill Lichtenstein’s documentary “WBCN and The American Revolution” and Ryan Walsh’s book “Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968.” With these recent releases, Boston’s historic, untold counterculture commands national attention. Boston was an epicenter of this movement 50 years ago, blossoming with experimentation that had widespread impact, but lurked in the shadows of what came out of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district and New York City’s Greenwich Village. “All those incredible publications, radio stations, institutions ... had their time and passed away… That’s why so much of this has gone unpublicized, because those important institutions did not prove to be sustainable. So we’re doing archaeology,” Giuliano said.

This book comes out during a time of political divisiveness in America and a renewed emphasis on nationalism worldwide. “The era of Trump is having an impact on an emerging generation and the hope of this book is that it’s available to a young reader that might look to it, be inspired by what moved us at our time and that one would hope for a similar kind of movement of activism in the arts today,” he said. After all, political revolution is fueled by arts and culture. “Protest in those days wasn’t just showing up for a demonstration on Boston Common or calling a congressman. The whole culture played a role in the change,” Lichtenstein told Giuliano in an interview.

That culture was splashed across the papers. DigBoston is the only alt-weekly in Boston today, but back then, there were many to pick up off the streets: Avatar, Broadside, Boston After Dark, Boston Phoenix, Cambridge Phoenix, and The Real Paper, to name a few. With so many college students in Boston, alt-weeklies had no shortage of eager writers who joined upon graduating. The writing stood out from other newspapers — it was spunky, edgy, and writers’ distinct personalities shined. Harper Barnes, editor of the Cambridge Phoenix, called the paper a “hippie project” and a “personal newspaper” in his interview with Giuliano. As an editor, he struck a balance between reporting on serious political topics and maintaining a strong personality for the paper. “There was a lot of pride in experimentation that we felt that we were writing in a fresh new manner. It was the new journalism,” Giuliano said.

As bold political and arts coverage filled papers, new sounds also filled airwaves. Before the counterculture era, radio stations like WBCN played classical music. Convinced by entrepreneur Ray Riepen, WBCN founder T. Mitchell Hastings shifted programming from classical to all rock, 24 hours a day, with young DJs hired out of college. “Album-oriented rock meant a complete war on the Top 40 playlists. The record companies saw that they could break new bands,” Giuliano said.

Album-oriented programming was a novel way to promote emerging bands that played rock venues like The Boston Tea Party. Because of the natural collaboration between print media, radio, music promoters, and music venue managers, bands like Boston, J. Geils, The Cars, Aerosmith, and Nervous Eaters gained a following and planted roots in the Boston counterculture. Maxanne Sartori, one of the few women DJs, carved a legacy in developing new acts. “Maxanne relentlessly promoted a song called ‘Dream On’ by Aerosmith. Maxanne could well be credited for the fact that today Aerosmith is a super, super group globally,” Giuliano said.

Despite the feminist, LGBTQ+, and racial justice movements bubbling in Boston, there wasn’t much representation for women, queer people or people of color in radio. In fact, it was because of a protest against WBCN for not having women on air that they brought in Sartori and started “Bread and Roses,” a weekly one-hour slot for women. “It would be incorrect to say that feminism wasn’t very, very important in Boston. If it was well represented in the media or not, that’s a complex question,” Giuliano said. “There’s no question that [WBCN] was all kind of a boy’s club.”

Though the counterculture was rife with dynamic experimentation, psychedelic drugs, and carefree joy, there was always a darker undercurrent of conflict that threatened the dream. Publishers were at each other’s necks. Radio stations faced the threat of commercialization. By 1980, The Real Paper folded, WBCN lost its luster, and The Boston Tea Party was 10 years gone. “By the 1980s that radicalism got mainstreamed... All of the idealism that we represented got subverted into commercialism. It kind of filtered out and disappeared,” Giuliano said.

The city composition morphed from earth toned bricks into steel and glass. Throughout the years, Boston has become even more commercialized and gentrified as artists lose spaces to live, work, practice and play. While Boston’s rich counterculture seems like a distant memory, the socio-political unrest today feels ripe for a new manifestation. “Counterculture in Boston” proves Boston’s place in the nationwide counterculture movements five decades ago — and calls a new generation to action.