Advertisement

How CSI-Style Science Helped The Peabody Essex Museum Tell A Rare Female Form's Story

Resume

In 2005, Peabody Essex Museum curator Dan Finamore got a tip on a carving up for auction. It was a figurehead, one of those often full-length, female forms that decorated the bows of ships between the 16th and 20th centuries. But this lady appeared to be made by a famous artist.

“When we were first alerted to the existence of this figurehead, there were a couple of people who dared breathe sort of quietly 'maybe it’s William Rush,' sort of a consummate attribution of a great, early American sculptor who had a lot of followers, a lot of copyists,” said Finamore, the curator of maritime art and history.

Rush has been called the father of American sculpture. He’s known for his busts of prominent figures, along with public statues and building ornaments in his hometown of Philadelphia. But the artist also created figureheads for Naval frigates in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Finamore told me the one on the block was unusually elegant and compelling.

“It has seen the world, so to speak. It has been exposed to the worst of the worst,” the curator said. “It's amazing that anything survives in those instances, so for us to find one that's really still mostly solid wood and shows the artist’s chisel work — that's amazing.”

The figurehead’s draping, neoclassical dress led Finamore to suspect it was from the early 1800s. But confirming Rush’s handiwork was daunting. There was no signature, and the object was riddled with damage. A long crack ran from her throat almost to her knees.

Even so, Finamore took a leap and negotiated purchase of the mysterious object at Christie's Auction House. Then, after sailing the high seas to faraway ports, it ended up battered and broken on the PEM's 21st century lab table.

“We've been calling this sort of Rush CSI,” said the museum's Conservator of Objects Mimi Leveque with a laugh. “I mean, that is what conservation is in many ways because we are trying to get back to the original history of objects.”

Piecing together the story behind this beautiful victim of time required collaborative sleuthing and meticulous digging.

“She's like an archeological site, so we wanted to make sure that we preserved as much as we possibly could."

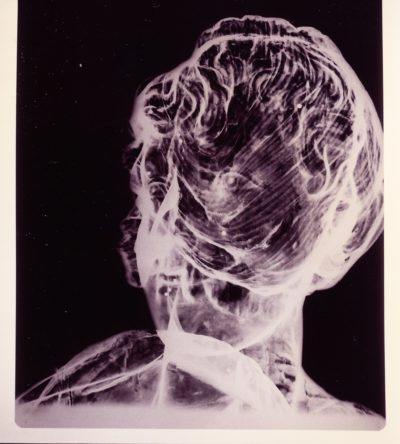

The conservation team turned to forensic imaging to help build the figurehead’s narrative.

“And the X-rays, first of all, showed an entire history of nails,” Leveque said as she pulled up a power point presentation documenting the lab's investigation. “And we found that there was buckshot in her.”

The shrapnel was a mystery, but those nails offered a clue to scholars the team consulted who know Rush’s technique. He used large spikes to connect hunks of wood he’d carve then paint over to make the amalgamation look whole.

The X-rays also revealed 30 layers of paint — the top 14 were white. To tell the figurehead’s story Leveque and the curator debated over how much to remove to try to reach its original colors.

“That's why it took 10 years,” Leveque said laughing again. “We carefully stripped every layer off, one layer at a time. We used a nontoxic stripping agent, and did it with scalpels.”

The process allowed them to look through time, each layer of color revealing clues. Around the mid-1800s, the figurehead's shawl was burgundy, a hue made fashionable by Queen Victoria.

Eventually conservators found the original color scheme for the sculpture’s attire. Her shawl was a robin’s egg blue. The dress peach pastel. They believe this was how she would have been seen on the water.

Finamore also remembers moving up to the carving’s face.

“The very first pink that we saw was on the lips,” he said. “And we thought, ‘Someone's just painted a face on here — isn't that gruesome?’ "

Soon they realized they’d hit the earliest coat of paint on those lips.

Then came another revelation.

“The eyes were the ‘ah ha’ moment for us,” Finamore continued, “because we knew that Rush always carved his pupils and then did a little deeply radiated line around for the iris. But with all that paint we could just stare down into the blank pit of the eyes.”

Beneath the paint they discovered what they believed to be Rush’s signature eyeballs. And the figurehead’s face looked a lot like a model named Louisa who famously sat for Rush. But Finamore says that’s not confirmed. Even so, he believes the evidence amassed over 10 years adds up.

“There are probably people who would say Rush didn’t sign this piece and therefore it's not by Rush,” Finamore mused. But then he said: “Show me that it's not by Rush, I think you’d be very hard pressed to find another carver who could have executed this.”

The curator and conservator feel they gave the figurehead what they refer to as an “honest treatment” for her long-awaited debut in the PEM’s just-opened expansion.

Back at the conservation lab, Leveque was satisfied, but also wistful, about her former constant companion.

“She lived on this table for 10 years, and the first day after she went up into the gallery it was like that empty nest syndrome,” the conservator recalled. “The whole lab just seemed so empty.”

Now the figurehead will have a lot of company hanging from her perch at ship bow height on the wall in the museum’s new maritime gallery. Her eyes stare off, looking like they’re lost in some long-ago horizon, as a soundtrack of waves crashes around her.

The massive torso crack is filled and her colors are alive. But one foot remains missing. The conservator and curator left it as they found it, deliberately, to help visitors understand her long, treacherous journey to Salem.

This segment aired on October 15, 2019.