Advertisement

In 'Walls Turned Sideways,' Artists Question The 'Justice' Of Our Justice System

Walls barricade, block, limit and impede, and when they’re part of a prisoner’s cell, they curb more than just physical movement. They limit social reintegration, employment opportunities and family relationships. They can become a means of social control and segregation, ultimately shredding the social fabric — especially with more than 2.3 million Americans living sequestered in prisons, more than any other country.

Yet, political activist and academic Angela Davis once famously suggested a glimmer of hope in the limiting nature of walls. “Walls turned sideways are bridges,” she said.

That phrase is the starting point for “Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System,” an exhibit at the Tufts Aidekman Arts Center. The show includes 51 works by 34 artists who in the past 40 years have examined aspects of a sprawling system that now imprisons nearly 25% of the world’s incarcerated, even while the country itself makes up only a scant 5% of the global population.

“The exhibition points to how vast the justice system is and how it touches us all differently, but significantly,” says Abigail Satinsky, organizer of the exhibition. “It brings the lived experience of people that are in the justice system to life in a different way.”

And most importantly, says Risa Puleo, an independent curator who organized the original exhibit when it first appeared at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in 2018, it allows artists to add their own unique perspectives on a system that seems close to broken.

Puleo writes in the extensive catalogue that accompanies the exhibit that artists are “capable of shifting perspectives on a problem in innovative ways, and as an agent in change-making itself.”

“Artists are approaching the problems of the criminal justice system, mass incarceration, and the prison-industrial complex from radically different perspectives than legislators, police officers, lawyers, and judges,” says Puleo. They work “in tandem with those directly and most often affected by this system to bring awareness to its abuses and prejudices.”

A lot of artistic practice, she says, culminates in direct community action that changes policies, lives, or at least minds.

Advertisement

“Artists are thinking about how to transform our understanding of that system,” adds Satinsky. “They're doing that through studio projects, working with communities, through direct collaboration, through documentation, through advocacy.”

The exhibit spans all mediums, including video, installation, photography and painting, and is organized into three thematic categories, “Ground,” “Figure” and “Bridges.” Works falling into the first two categories are on display in the gallery while “Bridges” is mostly left to critical essays that are part of the show catalogue as well as a two-day March symposium held in partnership with the Tufts University Prison Initiative, which offers associate degree programs and learning partnerships between the incarcerated and Tufts students.

Circulating through the exhibit, visitors find themselves also circulating through a sweeping “system” that begins with the act of profiling, then quickly moves to arrest, processing, incarceration and finally, reentry back into society. Interspersed among the works examining policing, the courts and prison life are pieces considering the stark setting of the prison itself. Prisons are compared to other “institutions of collection” including museums, libraries, asylums and zoos. These are the institutions, says Satinsky, that “manage knowledge, objects, possessions and bodies.”

In the “Ground” category, Andrea Fraser’s “Index” (2011) and “Index II” (2014) adroitly chart how prisons and museums have expanded simultaneously. As the top 1% of the population has accumulated wealth exceeding that of the bottom 80%, the art market surges, museums build fancy new wings and the bloated prison-industrial complex swells. The rich get richer, it seems, while far too many of the rest of us wind up in jail.

Ashley Hunt presents photographs of those jails in his series “Degrees of Visibility.” Between 2010 to present day, Hunt has visited 250 prisons, jails, penitentiaries and detention centers in all 50 states, snapping photographs from the nearest public roads. His landscape studies reveal an omnipresent prison industry, which, while ubiquitous, remains largely invisible, glimpsed only at a distance, behind overpasses, across fields and vast parking lots.

“It's just beyond our view,” says Satinsky, “but it's embedded in our everyday landscape.”

Maria Gaspar designed “Haunting Raises Specters” (2015), an installation reproducing an image of the entire north-facing wall of Chicago’s Cook County Jail printed on a sheer curtain. Standing before the diaphanous drape, viewers can move the drape back and forth, asking themselves on which side of the wall they really stand.

In the category of “Figure,” a series of potent works consider how the justice system leaves its indelible mark on individuals.

Suzanne Lacy, along with Julio Morales and Unique Holland, held performances addressing profiling in the 1990s. The video “Code 33: Emergency, Clear the Air!” (1997-1999) came out of a three-year project Lacy led with Oakland youth exploring ways to reduce police hostility toward young people who are often assumed to be troublemakers, even when they’re not.

Autumn Knight offers a video, “Do Not Leave Me” (2013), of a performance in which she reenacts an arrest. Knight is seen openly carrying a gun before lying prone on the floor with arms outstretched. The piece underscores the discriminatory nature of open carry laws in which the only people allowed to openly carry a firearm happen to be white.

Once individuals are incarcerated, they can face years of separation from family and friends. In “The Jumpsuit Project: After the Wake Up” (2017), Sherrill Roland explores the passage of time through the accumulation of marks on a cell wall. In this participatory installation, Roland, a former prisoner incarcerated for a crime he did not commit, recreates a battered cell wall. It was his job while in prison to paint over cells that were never cleaned or scraped in preparation for new inmates. In his piece, he invites gallery visitors to leave their own marks which will be regularly “erased” over the course of the exhibit with layers of fresh paint that never completely obscure marks left by earlier visitors.

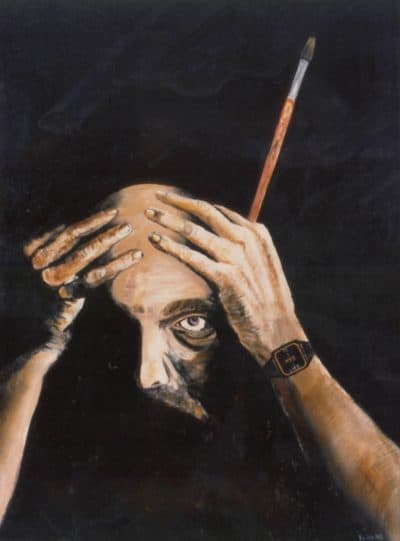

Once prisoners do their time, they do not necessarily experience freedom when it’s all over. And sometimes in order to get their freedom, they must rely on lucky breaks and serendipity. Anthony Papa was sentenced to 15 years to life in prison for a nonviolent drug offense in 1993. It was the same year that artist Mike Kelley happened to be looking for an artist in prison who was a murderer to show at the Whitney Museum in New York. Though Papa was no murderer, he submitted his painting “15 to Life” (1988) to the Whitney and his work got accepted. After showing at the museum, Papa was able to use the exhibit as leverage with the prison parole board who granted him release. Ever since, Papa has worked as an artist-advocate to fight for changes in legislation around drug-related crimes.

When prisoners don’t exit, they die. Death in prison may come of violence, illness or natural causes. And some prisoners, of course, are executed. Luis Camnitzer exhibits a powerful text-based work entitled “Last Words” (2008) that is a composite of the final words of men executed on Texas’ death row as transcribed by an official in the moment before they were administered a lethal dose of poison. What stands out most in the text is the simple word “love.”

Puleo says she chose the title of the show because the walls as bridges quote suggests that walls can be “tippable, moveable, and malleable.” And maybe that goes for prison walls too.

"Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System” runs at the Aidekman Art Center in Medford from Jan. 23 to April 19. An opening reception and public conversation with curator Risa Puleo and artist Autumn Knight will take place Jan. 23 from 6 to 8 p.m.