Advertisement

Commentary

What Tschabalala Self's 'Out of Body' at the ICA Taught Me About My Own Body

Like many other black girls, I developed early. Which meant, from an early age, my body dictated how others treated me.

By the time I was 11 years old, my mother and I were cruising stores at the mall for DDD cup bras. The summer after my seventeenth birthday, I was going under the knife to reduce the size of my chest. From the men leering at me on the street to the school nurse who swore I was promiscuous because of my chest size, society dictated that I was a (sexually active) woman before I even knew what it meant to be one.

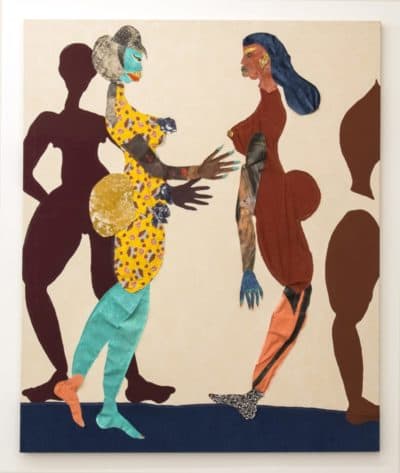

Many of these memories welled to the surface as I walked through Tschabalala Self’s “Out of Body” exhibit at the ICA. Self is undoubtedly a darling of the fine art world, known for her graphic, abstract pieces created through sewing, assemblage and painting. Self’s process includes the deconstruction and reconstruction of fabrics, materials and form. This tradition was passed down to her from her mother. “She used to sew a lot of things in the house,” Self tells me as we walk through “Out of Body.” “Our curtains, our special outfits. It was a lot of re-purposing of old things into new things.”

In many ways, Self’s pieces are imbued with this practice of transformation. Much of her work requires breaking down of figure into its simplest parts and reassembling it together again, some into what she calls “avatars.” It’s an experiment of sorts, Self tells me, to see how abstraction impacts the gendering and racializing of a figure. I think back to the days I walked home in my oversized jackets, trying to hide my chest from voyeurs. As abstracted my breasts must’ve seemed beneath a bright orange, shapeless windbreaker, I was still consistently and repeatedly treated as a woman, and more than that, as a black woman who wanted the attention.

“It’s more about how a body is felt or seen as opposed to how it exists in reality,” Self elaborates. This explains the exaggeration of body parts in her work. “When you’re looking or interacting with a person, you’re not focusing on their entire form....you’re focusing on the body part you interact with the most.” The abstraction is a way for Self to “abandon the framework of realism,” she tells me. “So that now, we can begin to have conversations about identity, history or spirituality.”

Historically, the bodies (and body parts) of black people, specifically Black women, have been the subject of scientific and anthropological criticism, scrutiny and myth making. We can recall the case of Saartje Baartman, whose servitude as a European circus attraction was propelled by a fascination with her large buttocks and vulva, though her backside was considered normal in her culture. Or we can discuss the “Mandingo” archetype and how it mirrors a cultural obsession (rooted in racism) with the sexual prowess (and reproductive organs) of black men. Everywhere, the “exaggeration” of the black form is exoticized, fetishized or demonized and myths or stereotypes inevitably follow.

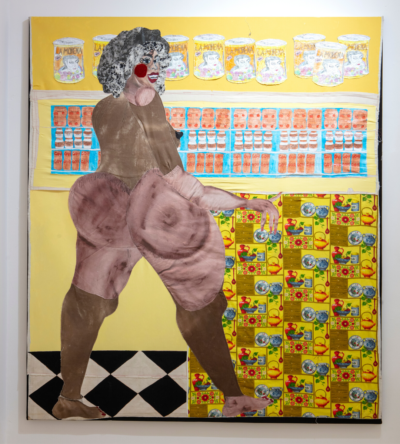

So as much as Self’s pieces may appear “abstract” or “exaggerated,” they’re very much rooted in black reality. As I peer up at “Ol'Bay,” I think of myself and the black femmes in my life who have similar body types. I recall my aunts wearing baggy trousers to work, afraid of being seen as unprofessional because of their hips and buttocks. I recall my cousins being hit on by adult men because the men said “they look grown.” Black women are no strangers to our body parts being hyperbolized, hyper sexualized and then censored by voyeurs. But in “Out of Body,” Self hands us back the agency and autonomy Western culture has pilfered.

Self’s pieces intentionally embrace and eschew these exaggerations and myths to upend the established canon when it comes to the bodies of black people. Self points out that, “If you’re living life in a body that others identify as feminine or masculine, there may be parts of your body that you focus on more yourself as well.” Body parts like lips, buttocks and thighs can seem larger than life in Self’s work, but in reality, many of us with bodies that are scrutinized at the intersection of race and gender already relate to the “exaggeration.” For us, exaggeration is simply another aspect of our reality.

What Self gives us in “Out of Body” is a blueprint of what it looks like to both create and exist outside of a politicized context. It’s inaccurate to say that there are no political underpinnings in her work, simply because whoever views the work will bring those political or cultural connotations with them. But in “Out of Body,” the figures exist beyond the realm of voyeurism.

Self's figures aren’t concerned with your opinions on their exposed or covered body parts. They’re not bothered by your thoughts on their thick thighs, exposed penis, generous buttocks or spread vulva. Moreover, many of these figures are engaged in everyday activities, like perusing a bodega, reclining on a bed or walking down the street. They’re striking back at policing and censorship by simply existing.

The reality is that black people and black women aren’t required to live our lives as objects “of a political state,” Self pointed out in an interview with I Weigh Magazine. Our lives and bodies are not props for conversation or debate, nor are we obligated to dismantle tropes about black womanhood through our behavior or dress. As surely as Self sews her pieces together, she’s also steadily unraveling the stitching of a tangled discourse about black womanhood.

Being a black woman can mean already feeling hyper visible, invisible, hyper-sexualized and dehumanized simultaneously. There are so few spaces where we can just be. But “Out of Body” reminded me that my power lies in just that. That by simply being, I am an avatar of my own making, autonomous and nuanced.

Perhaps that’s where revolution truly, truly begins.

“Tschabalala Self: Out of Body” runs through July 5 at the ICA.