Advertisement

19th-Century Dressmaker, Who Bought Her Freedom, Showcased At PEM

The business of fashion has been dominated by men for centuries. But a new exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem is celebrating pioneering women who've influenced the industry's evolution. Among the more than 100 female designers represented is Elizabeth Keckly, a former enslaved person who — against a myriad of odds — went on to become Mary Todd Lincoln's dressmaker.

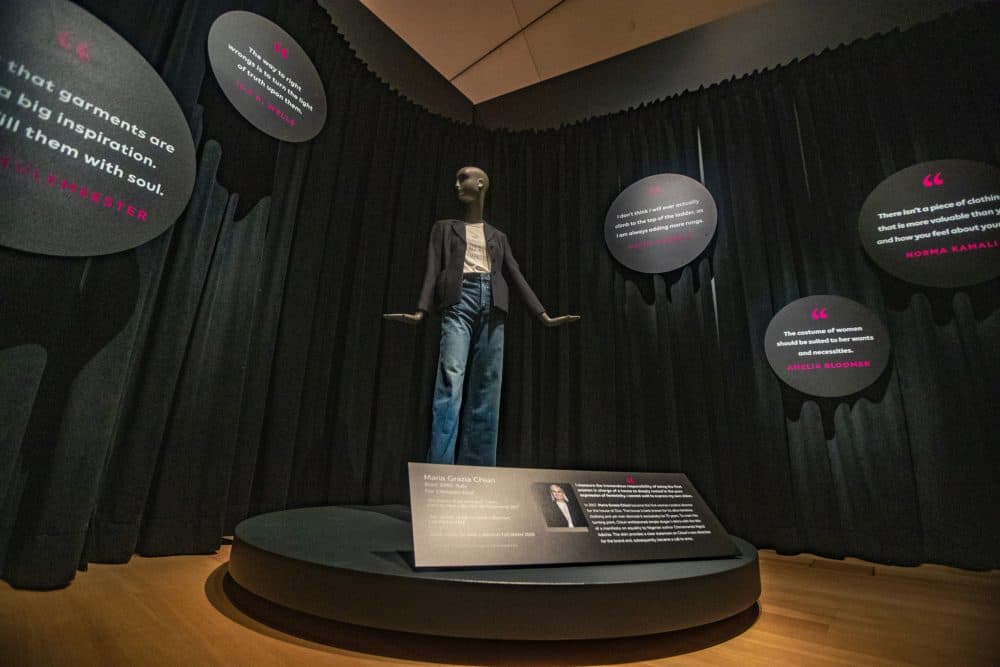

“Made It: The Women Who Revolutionized Fashion,” is populated by an army of impeccably-dressed mannequins. The show was organized to celebrate the 100th anniversary of women winning the right to vote. The first ensemble visitors see is contemporary — blue jeans, black blazer, white T-shirt with the slogan “We Should All Be Feminists” across the chest. It was designed by Maria Grazia Chiuri, the first female head of Christian Dior.

Steps away shimmering, poofy gowns represent women who challenged the male-run European guild system in 1675 by creating their own.

Then a black-and-white buffalo plaid dress comes into view. The Victorian-era creation, on loan from the Chicago History Museum, is attributed to Elizabeth Keckly.

“It is purported to have been owned by Mary Todd Lincoln, who was probably one of her most famous and supportive customers,” Petra Slinkard said.

Slinkard is the museum's curator of fashion and textiles. She said this dress — and the woman credited with making it — embody the exhibition's narrative thread of female fortitude and ingenuity. “Their stories intersect with the history of women's ongoing struggle for equality.”

Keckly was born into slavery in the United States in 1818. Her mother taught her how to sew when she was a child. Keckly helped mend and make clothes for the family that owned them both, “and she became an extremely well-versed and skilled dressmaker,” Slinkard said.

Keckly's needle skills would help her escape a life of servitude.

Before dying, her mother revealed that their owner, Armistead Burwell, was Keckly's biological father. While growing up with his family in Virginia she endured whippings and other abuse. As a young woman, Keckly was raped and gave birth to her only son, George.

Eventually, the talented seamstress moved to Missouri with her owners, who were struggling financially. She supported them – while making her own money – by making dresses for St. Louis socialites. Then, in 1855, Keckly asked to purchase her and her son's freedom.

“Her owner at the time thought that he was going to propose an amount that would have been very hard to achieve for a Black woman in the early 1800s, which was $1200 dollars,” Slinkard said.

Keckly proved him wrong and made her way to Washington D.C. where she opened her own shop. “She wanted to keep pushing, she wanted to be successful,” Slinkard said, “and she knew that she had the skill set to do it.”

Advertisement

Soon Keckly became the go-to dressmaker for the social and political elite. Look closely at Mary Todd Lincoln's dress with cape, Slinkard said, and we can see why customers — including Jefferson Davis's wife Varina — sought out Keckly's eye. The curator pointed to the large row of black buttons running down its front and the piping along the cuff of the sleeve.

“But also the swing to the cape that is worn above the very large cage, crinoline circular skirt really speaks to her skills as a dressmaker, but also as an artist,” Slinkard said, adding Keckly had an innate understanding of proportion which worked well for Mary Todd Lincoln because she was petite.

Keckly was more than the First Lady's dressmaker – she was also her confidante. Slinkard said they bonded, in part, because they'd both lost sons to the Civil War. But their relationship would come to an end a few years after President Lincoln was assassinated. In 1868 Keckley published a memoir titled, “Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House.”

“She was trying to portray Mrs. Lincoln as a real person who struggled emotionally and had been through some severe hardships,” Slinkard said. “And because of the time, because of her position, because of her race, the publication was not well received.”

According to author Jennifer Fleischner, Keckly's revealing book crossed boundaries for a lot of people, especially the First Lady.

“Mary expressed a sense of betrayal, particularly that letters that Mary Lincoln had written to Keckley were published in an appendix,” she said, “and that her private life — scenes in the White House with her husband, with her children – were now out there for the world to see.”

Fleischner, who's an English professor at Adelphi University in New York, explored the two women's complicated relationship in her own book, “Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave.” (She says while the seamstress's name has an “e” in her memoir, the historically correct spelling is Keckly.)

Fleischner said wide reaction to Keckly's memoir was damning because people – both white and Black – saw it as an audacious example of a servant peeking through keyholes. “Keckly became the 'angry Negro servant' and the target of incredibly vicious attacks,” Fleischner explained. “She lost clients from her business, and even other Black people were angry at her for stepping out, and felt perhaps targeted now or endangered somehow.”

Keckly was fully aware that her words would likely offend. In the preface to her book, she defended her “secret history” as a compassionate act of truth telling that would contextualize, for the world, Mary Todd Lincoln's life.

“It may be charged that I have written too freely on some questions, especially in regard to Mrs. Lincoln. I do not think so,” Keckly wrote.

Fleischner studies the narratives of enslaved people and said Keckly's use of the word “freely” is powerful. “She's not writing as a slave, or someone who's running as a fugitive, or as someone who was emancipated,” she said. “She's writing as someone who bought herself. And she's a woman, of course.”

Today historians value Keckly's memoir as a primary source that offers a rare glimpse inside her remarkable life, inside the White House and inside the nation's capital at a fraught time in U.S. history.

Keckly earned her power as a fashion maker in the nation's capital where white women wore what she told them to. “She was not just a dressmaker,” Fleischner explained, “she had the title of 'mantua-maker,' and that was a kind of bodice that not everybody could make. It was like glued to your body.”

After the memoir was published in 1868 Mary Todd Lincoln and Keckly never spoke again. The designer went on to lead the dress department at Wilberforce University, the nation's first college established and owned by Black educators. She was also a social activist who helped raise money for Civil War veterans and newly freed people. Keckly ultimately ran into financial troubles herself. She died of a stroke in 1907 in Washington D.C., at the Home for Destitute Women and Children, which she helped create.

More than a century later, Fleischner is delighted to know the dressmaker is included in an exhibition about female fashion pioneers and said, “She deserves it.”

This segment aired on January 29, 2021.