Advertisement

Advocates Strive Once More To Make Mass. Film Tax Credit Permanent

According to advocates of the Massachusetts’ film tax credit, a series of reforms recommended by the state Senate as part of the 2022 budget will destroy the commonwealth’s film industry just as it gets back on track from the pandemic and stands on the cusp of significant growth.

The House unanimously passed its budget, which includes language to keep the current film tax credit and remove its 2023 expiration. (A detailed summary of the credit can be found on the Massachusetts Film Office website.) But for its budget, the Senate Ways and Means Committee outlined four changes to the program, which on average accounts for between $60 and $80 million per year:

- Move the sunset date from Jan. 1, 2023 to Jan. 1, 2027

- Increase the minimum amount of in-state spending or in-state principal photography days from 50% to 75%

- Cap salaries eligible for the credit at $1 million

- Eliminate transferability of credits

Tinkering with an already successful credit makes no sense to the owner of Rule Boston Camera in Newton. John Rule says that making any one of the proposed changes may seem reasonable but could drop Massachusetts way down the list of locations that compete for major film projects. A 2019 report by Michael Thom ranks Massachusetts fifth in film tax credit spending behind New York, Louisiana, Georgia and Connecticut.

“Don’t be deceived by what sounds like minor modifications. They are not,” says Rule, who has more than 40 years of experience selling and renting professional camera packages for the kinds of projects that claim the credit. Without it, he says his current business would probably drop by at least 30%.

That would be an added blow since he had to lay off more than half of his staff during the pandemic. Yet he remains optimistic about the potential to rebuild. “I’ve never seen an environment more dynamic and successful and growing than what I’m seeing right now,” says Rule. Most recently, his company outfitted “The Tender Bar,” directed by George Clooney, starring Ben Affleck, and shot in Massachusetts earlier this year.

If his business could see a steady stream of movies similar in scope, Rule says he could replenish his ranks and even expand. “That would give me incentive to increase inventory and payroll to compete with larger companies around the country,” he says. But, in his opinion, that can only happen if the current film tax credit remains intact, ideally with the sunset removed.

That’s what the House voted to do 160-0 and what Senate budget amendment #846 filed by Sen. Michael Moore also endorses. The Senate expects to begin its budget debate on Tuesday, May 25. That morning, advocates for the credit plan to gather on the State House steps to express their concerns.

David Hartman, executive director of the Massachusetts Production Coalition, the group organizing the rally, says that four or five major movies will start shooting in Massachusetts in early June, making it one of the busiest seasons on record. Given what he calls “a perfect storm of business opportunity,” he thinks the choice is clear: Either actualize the infrastructure and ecosystem that’s been built in Massachusetts or say no to it.

The film tax credit has been hotly debated on and off since its 2005 adoption. In that time, other states have initiated, refined and, in some instances, repealed similar programs. Proponents often say that film production is about the bottom line and incentive programs attract business that would otherwise not exist. Critics, meanwhile, might oppose tax credits across the board, regardless of the industry, oppose favoring one industry over another or question the cost-benefit ratio of a particular credit.

A 2019 opinion released by the Pioneer Institute laid out an argument against film tax credits in Massachusetts, citing low job creation (3,000) and high cost per job created ($109,000). The Tax Foundation released similar findings in 2015.

Senate Ways and Means Committee Chair Michael Rodrigues told the State House News Service that the proposed reforms are based on the recommendations of the Tax Expenditure Review Commission (TERC). “We want to see more of the benefit be realized by Massachusetts residents and Massachusetts companies,” he said. In the comments section, the TERC noted, “Film credit has had no discernable impact beyond its one-time spending. Further, much of the initial spending that qualifies for the film credit occurs outside of Massachusetts, providing no benefit at all.”

Yet, film tax credit advocates believe that the data does not fully capture the depth of the credit’s impact and lacks proper analysis. For one, there’s always a lag time in numbers collected by the Department of Revenue. (A production shot in 2018 might not file until 2019 or 2020, for example.)

Irene Wachsler, who owns a Burlington accounting firm that has prepared more than 200 requests for the credit, ticks off receipts she sees for clothing stores, supermarkets, gas stations, fast food chains and other businesses that she thinks have no idea they benefit from film production. “I don’t think anyone has studied how many times that dollar has turned,” she says about the uncounted economic multipliers. She explains that when a film crew member tips a server at a restaurant, then that server gets a haircut and so on, those dollars keep getting spent in the state.

Securing long term success with the partially nomadic film industry is a “chicken, egg kind of thing,” according to Rule. A state needs what he calls a “permanently favorable environment” with a skilled workforce, enough infrastructure and a credit that can be counted on many years out, since projects need several years lead time to raise funds and book talent. He believes Massachusetts is almost there.

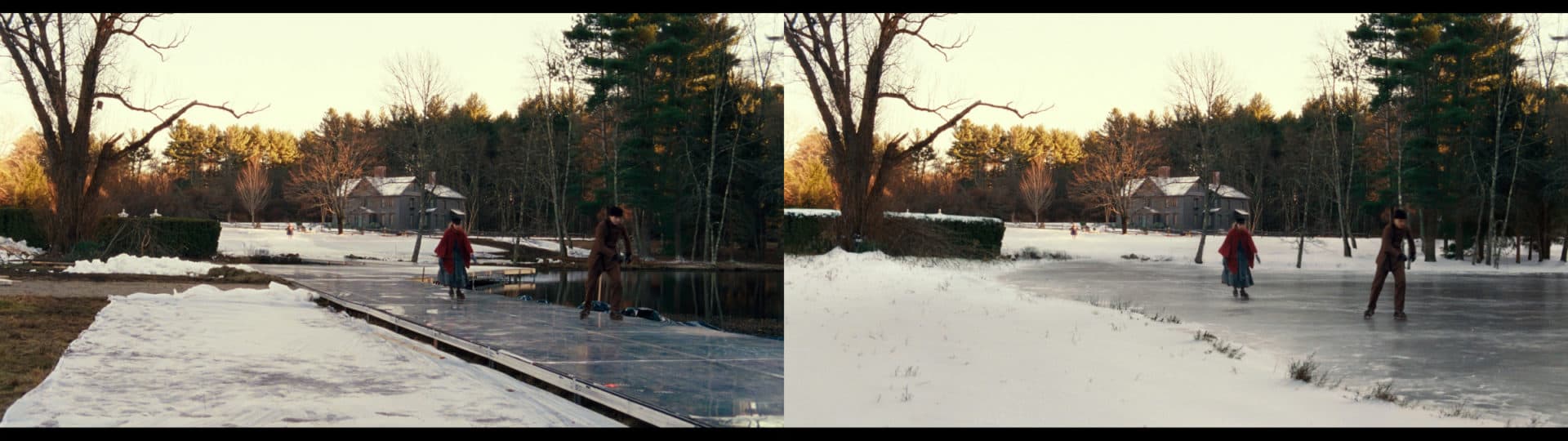

In 2010, Brian Drewes started Zero VFX in Boston, which handles special effects — like creating a skating pond for “Little Women” — in part because the credit existed. Now with about 50 employees, Drewes says the credit “allowed us to be entrepreneurs” and take more risks. In 2014, he spun off part of his business, Zync, which employed 80 software developers, and sold it to Google.

Drewes points out that in some states and Canada, the work he does has its own dedicated tax credit. Even without that, if Massachusetts can maintain its current momentum, he says, “We are actually looking to make even more investments. That’s why it’s kind of important that this stuff gets stabilized.”

He says he worries that changing the credit would put thousands of Massachusetts residents out of work. “If you look around a film set, it’s filled with normal people, literally your neighbors. Very few Hollywood elites.” To Drewes, the Senate’s plan “is poorly conceived and it would absolutely kill a lot of the industry.”