Advertisement

Seeing Red

How A Nationwide Cancer Scare Nearly Sank The Cranberry Industry

Resume

This story is Part 2 in a series on the rise and fall of U.S. cranberry sales in China. Part 1 is here. The stories aired in four parts. To hear the stories that aired Tuesday and Wednesday, click the given links or the audio players found in the post below.

It was an early November day when Arthur Flemming got some distressing news.

Flemming, who was the secretary of health, education and welfare under President Dwight Eisenhower, had just learned that samples of cranberries collected in Oregon and Washington were found to contain traces of aminotriazole — a herbicide which, according to some lab tests, could cause thyroid cancer in rats.

“Carcinogens had been banned for agricultural use the previous year, and so he said, 'We have a problem,' ” explained Robert Cox, head of special collections at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and author of the book "Massachusetts Cranberry Culture: A History from Bog to Table."

In a couple of weeks, cranberries would be hitting the Thanksgiving tables of millions of Americans. On Nov. 9, 1959, Flemming issued a statement warning the public of the contamination and the potential cancer risk.

According to news reports at the time, Flemming added that if a “housewife” is unable to determine the origin and crop year of their cranberries, whether fresh or canned, she should avoid them “to be on the safe side.”

“And people, almost overnight, stopped buying," Cox said.

Within hours, groceries stores around the country pulled cranberry products from their shelves. Cranberry sales were banned in Ohio, Chicago and San Francisco. Days later, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) seized a shipment of cranberry sauce from Massachusetts, and a band called Robert Williams and The Groovers even wrote a song called "Cranberry Blues" to capture the moment.

“My reaction at the beginning was, ‘Oh my god. It's over. This cannot be my career,’ ” said John Decas, co-owner of Decas Cranberry Products in Carver.

At the time of Flemming's announcement, Decas was in his mid-20s and had just started working full-time for the family business.

“We had 40 trailer loads of cranberries canceled within one hour after that announcement,” Decas said, and for the rest of that year, they didn’t sell a single berry.

It didn’t help that, a few days before Thanksgiving, LIFE magazine devoted a full page to recommending substitutes for cranberry sauce (including currant jelly, sour cherry preserves and pickled watermelon rind). And the White House, for its Thanksgiving dinner, replaced cranberry sauce with applesauce.

“That was another punch in the gut,” Decas said.

At the time, there was pushback from people in the cranberry industry, some politicians and some members of the scientific and medical community.

According to Cox, one professor of medicine at Tufts University was quoted as claiming, “If you ate 2,200 pounds of cranberries labeled as ‘badly contaminated’ every day of your life, the effect would be the same as if you had eaten one turnip daily, and neither would cause cancer.”

Nevertheless, the industry agreed to cooperate with the government, holding back tons of fresh cranberries and cranberry products until lab tests could show they were free from contamination.

By Thanksgiving, the FDA had cleared about 16.6 million pounds of fruit as free of aminotriazole, and traces of the chemical were found in only about 1% of the fruit inspected. A few years later, in 1962, Congress paid growers about $8.5 million to compensate them for lost revenue.

Still, the damage was done. At nearly 1.25 million barrels, the 1959 cranberry crop was the largest in history, according to The New York Times. And much of that fruit — valued at $45-50 million — would remain unsold, even after it was declared safe. For the next few years, sales slumped.

“Now that you put cancer in the mind of the consumer, how long is it going to take to deal with that and get back to normal?” Decas recalled thinking.

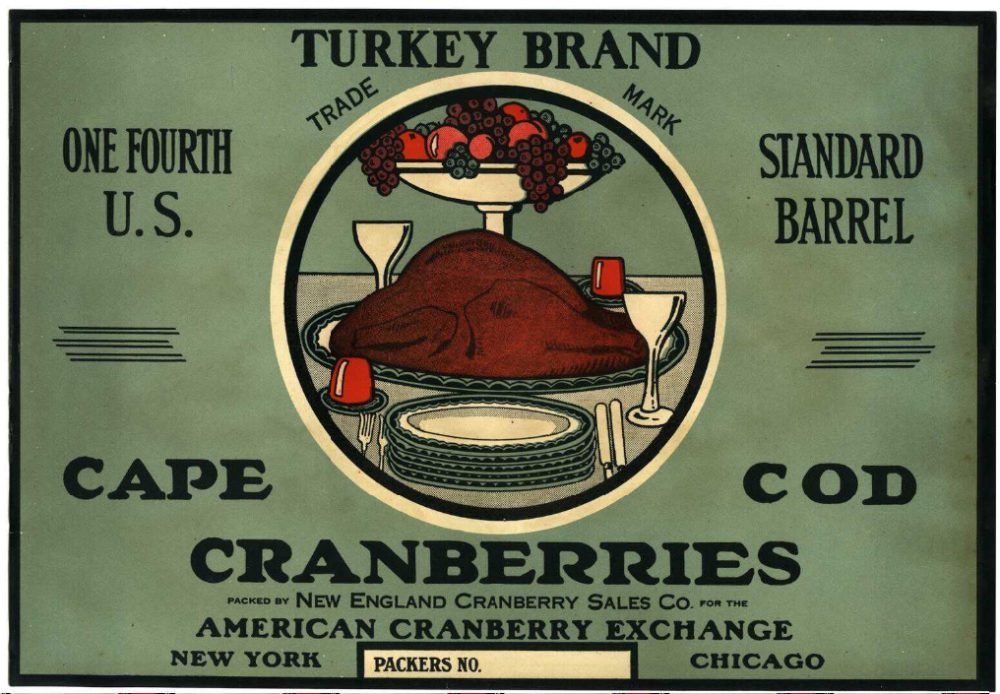

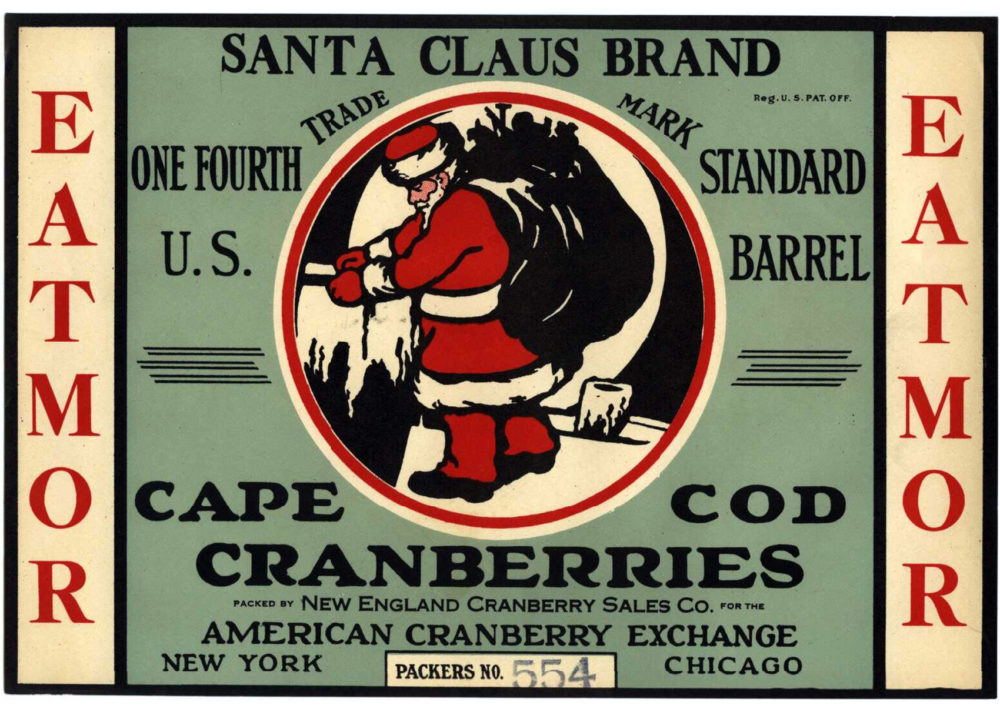

Part of what made the Cranberry Scare of 1959 so hard on producers like Decas was timing. Back then, almost all cranberries were sold around Thanksgiving or Christmas. As a result, the Cranberry Scare was a wake up call for the industry: If it was going to survive another unexpected crisis, it needed to spread out the risk by getting consumers to buy cranberries year-round.

In terms of difficulty, said Cox, trying to sell cranberries out of season was something like the Christmas tree industry attempting to sell Christmas trees year-round.

“You’re going against the cultural default,” he said.

But in the early 1960s, Massachusetts-based Ocean Spray brought on a new CEO, Edward Gelsthorpe, who would try to do just that. In search of a product with all-seasons appeal, the company started tinkering with one of its niche products: Cranberry Juice Cocktail. At the time, it was sold only in New England, and there was a good reason for that.

“It had actually been formulated to meet the taste of cranberry growers,” Gelsthorpe explained in a 1988 documentary by the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers' Association. “You’ve seen cranberry growers. They can pick up a handful of cranberries off the vine and eat them, and that was about the way cranberry juice cocktail tasted. So we did the not-so-brilliant thing of putting more water and more sugar in it, and it then became a very palatable drink.”

The new formulation was rolled out nationwide, accompanied by ads challenging consumers to “Drink Different.” Before long, sales of Cranberry Juice Cocktail took off, followed by juice blends such as Cran-apple and other new products.

Some of these experiments, such as “Dip ‘n ‘Bake,” a cranberry-based glaze for baked meats, which came in flavors like barbecue and Italian, didn't exactly fly off the shelves.

But the growth of the juice category was enough to take cranberries from being a once-a-year food to something you could consume in any season. Some marketing even suggested replacing your morning glass of orange juice with Cranberry Juice Cocktail because of its superior “food energy.” (Turns out that “food energy” was merely ad-speak for calories. In 1972, the company was forced to retract that phrase after the Federal Trade Commission called it misleading.)

Juice-for-the-masses was an innovation that changed the cranberry industry, but it wasn’t the first or the last.

In 1912, Marcus Urann, an attorney and cranberry grower, began selling canned cranberry sauce under the name Ocean Spray Preserving Company.

“As modest as this seems, Urann’s maneuver was revolutionary,” writes Cox in "Massachusetts Cranberry Culture." "For a fruit that had been marketed almost exclusively as a fresh product, it was a radical proposal to cook and can.”

In the 1980s, when the cost of bottling and canning rose, Ocean Spray became the first American company to put its beverages in aseptic packages, or what most people today call juice boxes. At the time, the company touted the new packaging as “paper bottles.”

Then, in the late 1990s, when a glut of cranberries sent prices sinking, companies like Ocean Spray and Decas threw their marketing muscle behind a product made from the cranberry skins that were leftover after juicing: sweetened dried cranberries. In the years that followed, sales of the little shriveled, sugary nubs soared.

“Dried cranberries are in such demand now that the juice has almost become the byproduct of the industry,” said Brian Wick, executive director of the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers’ Association.

Nowadays, with most cranberry growers swimming in surplus fruit, prices falling and a trade war pinching international sales, Wick said he hopes the industry can come up with another hit.

It’s worth noting that the industry’s drive to come up with new products has not only been spurred by market shocks like the Cranberry Scare. It has also been necessitated by Ocean Spray’s structure as a grower-owned cooperative. That means the company, which claims to control about two-thirds of the world’s cranberry supply, is obligated to buy all of the fruit its members grow in a given season. Those hundreds of millions of tons of fruit have to go somewhere, or they weigh down the market price.

“The dried cranberry product was the big development of the 2000s,” Wick said. “Well, it's been almost 20 years now. We need something else.”

On that score, there are some newer concoctions out there, aimed at consumers who are not into juice or dried fruit. Cranberry-infused water, anyone? Or how about a chewable cranberry health supplement? Maybe these products will catch on over time. Maybe they won’t.

But if the industry succeeds in getting folks to consume cranberries in a whole new way, it wouldn’t be the first time.

This segment aired on September 19, 2019.