Advertisement

Holiday Hustle: Riding Along With An Amazon Flex Driver

This holiday season, millions of people are buying gifts online. And those orders aren’t just fulfilled by the U.S. Postal Service or companies like UPS and FedEx. In the case of Amazon, they’re also being delivered by an army of part-time gig workers commissioned through an app called Amazon Flex.

Launched in 2015, Amazon Flex allows people to sign up as independent contractors to make deliveries for Amazon, Amazon Fresh and Whole Foods. Many of those who join the platform are drawn by the flexibility of the job and the low barrier to entry. Basically, all you need is a driver’s license and a background check, then you watch some training videos, and you're good to go.

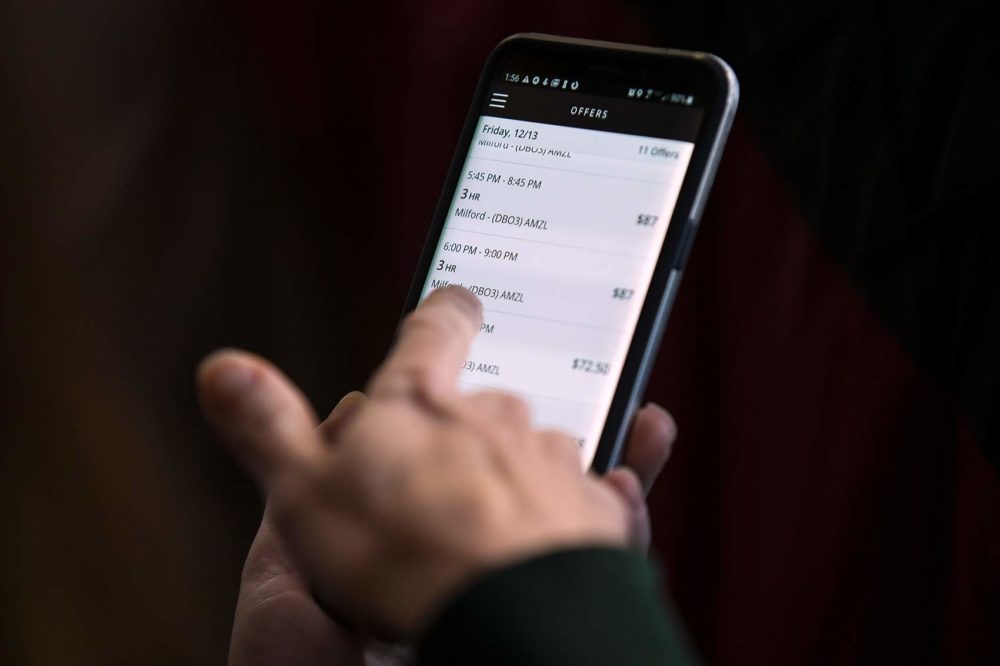

Once signed up, Flexers, as the drivers often refer to themselves, use the app to view available "blocks" — their term for shifts — usually two to four hours each. According to the Amazon Flex website, the rate for a block typically runs between $18-25 per hour.

But the rate for any particular block can change based on a variety of factors, so it helps to employ a bit of strategy.

"The closer you get to that starting time, the rates will start to raise," said Lynne, who is one of hundreds of Flex drivers in Massachusetts. Lynne asked to be identified by first name only because she worried that speaking to a reporter could jeopardize her work with Amazon, which is her primary source of income.

"It’s kind of like a game to see how high you can get it before that block disappears on you," she said.

In other words, grab a block too soon and you might leave money on the table. But wait too long to claim a block and someone else could take it. Finding the sweet spot requires vigilance, explained Lynne, who said she has been doing Flex work full time for almost two years.

"Swipe down on the app, it refreshes. And you basically have to do that constantly throughout the day to see what’s available for work." she said.

Lynne described the feeling of catching a block as addictive, almost like gambling. On good days, the job can pay as much as $30 an hour, which is more than she used to make as an administrative assistant.

On a recent afternoon, Lynne signed up for a 3.5-hour block worth $95. In her blue sedan, she drove to a large warehouse in Milford, one of about 150 “Amazon Delivery Stations” in the country, according to the company.

As she reached the outside of the warehouse, the Flex app prompted her to stop and take a selfie — a security measure implemented recently to deter drivers from using another Flexer's account.

Advertisement

Once inside the facility, Lynne drove slowly past a network of conveyor belts and chutes moving packages around the building. In the loading area, a shelf full of boxes and envelopes was waiting for her. After scanning the code printed on the packing list, she learned she had 18 packages to deliver, all in the Worcester area.

The next challenge: getting all of the boxes into her car. Lynne hoisted packages into the trunk and backseat, rearranging them until they fit, in a sort of real-life game of Tetris. Some of the larger items included a fancy pressure cooker, a child's car seat and a fish aquarium.

In the process of trying to wedge the car seat into her trunk, Lynne tore her thumb nail.

"I break a lot of nails doing this job," she said.

Eventually, the car was loaded up, and Lynne was back on the road. For the rest of the afternoon, her shift went something like this: punch in an address, drive to a house, grab a package, traverse an icy walkway, drop the package on the porch, scan the label to let Amazon know the delivery is complete, then jump back in the car and do it again.

By the end of her block, Lynne said this was a relatively easy shift. Still, she said, this job has its hazards: bad roads, lousy weather, scary dogs and slip-and-falls.

She recalled a time this past summer when she slipped on a customer’s wet stone walkway.

"My feet went straight out from under me and I landed straight on my back, and my teeth like clinked together," she said. "And I think the guy inside must have heard me because he peered out the door and said, 'Are you OK?' And I said, 'I think so,' and he said, 'All right,' and he shut the door and didn’t even help me up!"

Stories like this are among the reasons some labor policy experts are critical of Amazon Flex.

"The way that those people are being asked to do the work has exposed them to a level of risk that’s very different than a traditional [employee]," said David Weil, dean of the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University. "The mail deliverer who came to your house to deliver a package or the UPS driver was an employee of those companies, and they would be protected by a whole set of workplace laws."

For example, such employees are eligible for workers compensation if they’re injured, they are protected by anti-discrimination laws, and many are part of a union.

But not Amazon Flex drivers because they’re considered independent contractors.

"It's really a fiction that these jobs are somehow independent contractor jobs," said Weil, who has previously criticized companies such as Uber and Lyft for insisting that their drivers are not employees. "A real independent contractor … the key word there is 'independent.'"

Through the Amazon Flex app, Weil pointed out that the company exerts a lot of control over when work can be done, how much it pays, and what opportunities are available. The app also allows the company to track drivers' performance and punish those who fail to meet the standards set by Amazon.

All of these features make Flex more like a traditional manager-employee relationship, said Weill, just without many of the benefits of one.

In response to Weil’s criticisms, Amazon said in a statement that “the vast majority of deliveries make it to customers without issue.” The company added, “If delivery partners have any concerns or questions about their participation, they can always contact support through the Amazon Flex app for help.”

Amazon declined to provide exact number of registered Flex users in the U.S. or in Massachusetts. However, a Reddit group for Amazon Flex drivers has approximately 8,600 members, and a private Facebook group for Flex drivers in Massachusetts has over 800 members.

For some Flex drivers, the lack of benefits is less important than the ability to choose whether to work or not.

"I need my flexibility. To me, that's part of the trade off," said Dan Crea, a musician in Boston who spends part of the year touring. "I don't see why Amazon would give benefits to someone who might literally never work another day for them."

Crea said Flex work is a convenient way to supplement his income when he is home between gigs.

"I have no obligation to them other than the current shift I have today," he said.

Yet, among drivers who seek to make a living on the platform, the feeling that Amazon is ultimately in control is widespread.

In a Facebook group for Flex drivers in Massachusetts, many posters have commented that this year’s holiday shipping period seemed to offer fewer blocks than last year. Some believe this is because Amazon has increased its use of Delivery Service Partners, or DSPs, third-party private companies that contract for last-mile delivery — perhaps you’ve seen those boxy cargo vans, often adorned with the Amazon logo, coming down your street.

Others hypothesize that the algorithm that controls what blocks drivers can bid for has been tweaked to favor less experienced workers, reducing opportunities for those more skilled at using the app to maximize their pay.

According to Amazon, the blocks that Flex drivers see depend on “a variety of factors including a driver’s location, availability and meeting our service standards for delighting customers."

Whatever the reason, Lynne has noticed a drop off in available blocks, noting that she used to be able to get morning shifts. Now, the only blocks she sees are in the afternoon and evening, forcing her to do more deliveries after dark.

Despite this, she plans to stick with it. Although she hasn’t calculated how much she earns on an hourly basis, she estimates that she nets about $1,000 every few weeks after rent, groceries and other expenses.

"As long as I don’t go into the negatives each month, I consider myself good to go," she said.

Still, Lynne said, it feels like she works more now than she did when she was an administrative assistant. She's on the road seven days a week, for a total of about 35 hours—more if you count the time she spends on her phone swiping and trying to get a block.

"My day is taken up between looking for work, doing work, and then squeezing in a bite to eat here and there, which can be difficult," she said.

As a result, her schedule doesn’t leave much time for socializing or shopping.

Although when it comes to shopping, Lynne has found a solution that works for her: if there’s ever something she needs to buy, she said, she can usually order it on Amazon.

This segment aired on December 20, 2019.