Advertisement

Losing Touch With The Old Ways Of Finding Our Way

My mother was always a good navigator, which surprised me, since even as a kid I sensed that her relationship with the physical world was ambivalent at best. But as my father drove, she would confidently issue instructions based on the filigree of solid and dashed black lines and narrow, disjointed green ones on the map. I’d worry when she directed him to break away from the map’s straight, bold red lines into the lacey brush of rural routes and post roads. But invariably, just by following some symbols on a page with her lanolin-scented finger, she’d successfully steer us to somewhere we’d never been before.

As a child, I thought she was practicing magic. Now, of course, I recognize that she was doing one of the things that humans do best — translating an abstract representation into a literal guide, synthesizing simple rules of navigation with the power of imagination.

The analogue clock isn’t just a device; it’s a paradigm. It not only orients us in the physical world, but is a wellspring of analogies and guideposts.

So about 20 years ago, I was alarmed to realize that a swath of my daughter’s generation didn’t know how to tell time on an analogue device, only a digital one. It’s not that I think the former is inherently superior (though I confess that I find the sweep of hands more graceful and soothing than the click of digits). Instead, what worried me was the prospect that with the passing of old fashioned clocks, an entire generation would lose a powerful means of both visualizing and comprehending the world. After all, our understanding of fractions — of quarters and halves, of sixths and tenths — is based on how we segment the hour. Our recognition that the same moment can be expressed as minutes after one hour or as minutes before the next is informed by the subtle placement of two wands in a circle. And we use the array of numbers bordering that circle to describe not just time, but position in space (as in, “Do you see that UFO?” “Where?” “At 10 o’clock!”)

The analogue clock isn’t just a device; it’s a paradigm. It not only orients us in the physical world, but is a wellspring of analogies and guideposts.

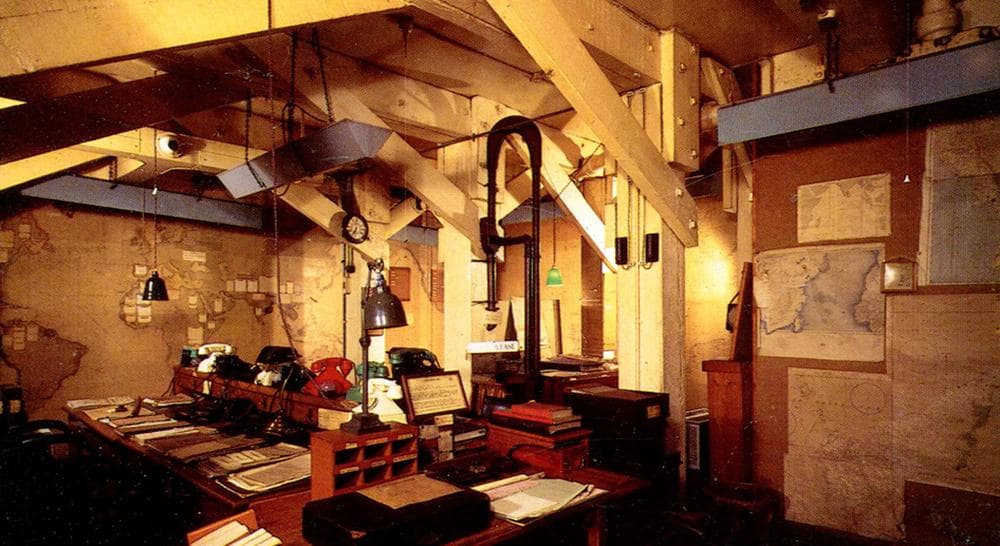

The same is true of maps, an insight that struck me with surprising emotional force as I recently wandered through Churchill War Rooms in London. A warren of dimly lit spaces in a Whitehall basement, this bunker served as a World War II military intelligence center and emergency meeting facility for Winston Churchill and his cabinet. The color-coded rotary telephones, the giant switchboard in a sound-proofed Transatlantic Telephone room for private conversations between Churchill and FDR, and the exhibits of laboriously written to-do lists for D-Day are all touching reminders of how fast and far technology has come in transforming our lives (and ability to inflict death) on a massive scale.

But it was the Map Room that suggested something more. Enormous maps of every continent and ocean covered the walls, each veined with delicate lines denoting supply convoys and battle fronts. Here, round the clock, representatives from the Army, Navy, and Air Force would continuously receive new information on the movements of troops and ships and update the maps’ jagged garlands. Next to each map, a large wooden case held small wooden boxes filled with the yarn and push pins used to create the lines. They looked like the raw materials for a school crafts project, like not-yet-assembled friendship bracelets and string art.

GPS systems allow us to arrive somewhere without knowing how we got there.

Today, the GPS systems installed in our cars and smart phones tell us where we’ve been and where to go. A female voice — usually strict, bordering on hectoring — tells us where to turn and how far to proceed before the next change in direction. The Garmin or Google Map may show us a rendered representation of where we are, but the picture is just color commentary. It’s the synthetic voice — not our own senses or sense of ourselves in space — that we obey. I’m okay with that. If this technology helps us feel freer to explore, then it’s worth the trade-off.

But just as digital clocks enabled my daughter and her friends to tell the time without understanding how it passes, GPS systems allow us to arrive somewhere without knowing how we got there. In the dim quiet of the Map Room, I was moved by the relics of a visual imagination linked by bits of yarn to an empathetic one. Fraying, their cheerful colors muted by the windowless light, those fragile lines represented tens of thousands of human beings connected by mud, bullet casings, and blood. And the people in that room knew it.

Related: No Detours, No Surprises, No Fun: What I Lost When I Stopped Getting Lost

This program aired on October 30, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.