Advertisement

The Anti-Donald Sterling: Remembering The Boston Celtics' Own Walter Brown

In the recent wake of Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling’s outrageous comments about people of color, it is perhaps heartening to remember that Boston once had an NBA owner who raised a different kind of national controversy when it came to matters of race.

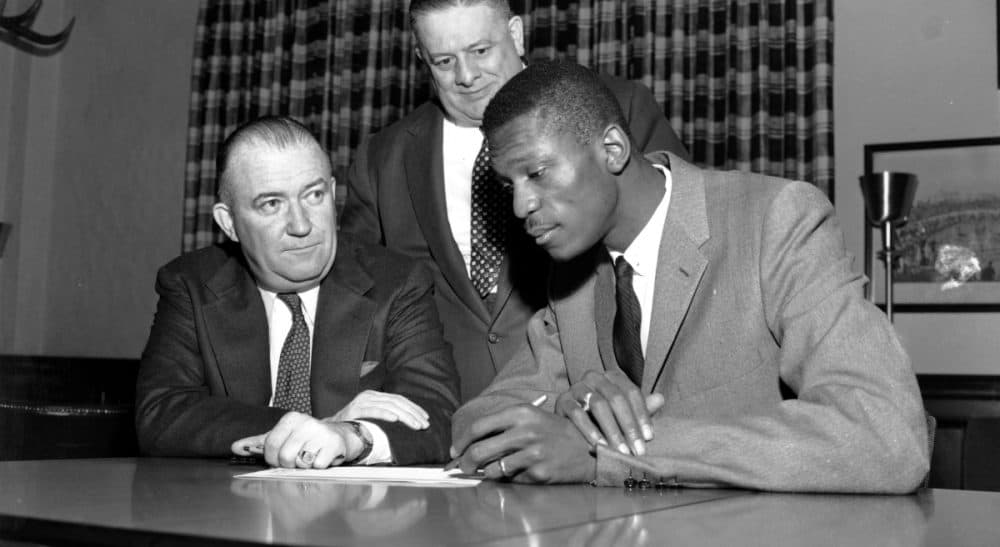

In 1950 Walter Brown shocked the professional sporting world when his Boston Celtics became the first team in NBA history to draft an African-American, 6-foot-6 All-American forward Chuck Cooper from Duquesne. Brown did this despite being condescendingly reminded by a fellow basketball mogul that Cooper was “a Negro” and therefore ineligible for consideration due to the league’s longstanding bar against athletes of color. In response, Brown famously maintained that he would have selected Cooper even if the latter had sprouted polka dots. “All I know is the kid can play basketball and we want him on the Boston Celtics,” he explained. For this strong vote of confidence, Cooper was eternally grateful. “THANK YOU FOR HAVING THE COURAGE TO OFFER ME A CHANCE IN PRO BASKETBALL,” he telegrammed Brown upon hearing the news. “I HOPE I’LL NEVER GIVE YOU CAUSE TO REGRET IT.”

Brown famously maintained that he would have selected Cooper even if the latter had sprouted polka dots.

Brown never did as Cooper became a highly regarded defensive specialist who scored 2,725 points in his seven-year pro playing career. More importantly, Brown’s bold move paved the way for other NBA teams to broaden their rosters to include blacks and other minority athletes, thereby opening the pro game up to a true national and international audience. “I am convinced that no team would have made the move on blacks then if the Celtics had not drafted me early,” Cooper later contended. Legendary Celtics coach and general manager Arnold “Red’ Auerbach, who passed away at the age of 89 in 2006, agreed. “There were a lot of things I learned from Walter,” he told the writer Joe Fitzgerald, “but I think the biggest thing he taught me — and this was by example — is that a man is a man is a man, the old Gertrude Stein crap. He told me, ‘Take a man for what he is and what he does, and forget everything else you’ve heard about him.’ Walter really believed that. He never gave a damn about a person’s color, religion, nationality or anything else. He simply cared about the man.”

In the years ahead the Celtics continued to garner a reputation for tolerance while pushing the envelope when it came to integrating the game. They were the first pro team, for example, to have five blacks on the floor at the same time. “The key to being a true Celtic, if there is one thing, is you have to be a man and accept responsibility for your actions,” Boston center Bill Russell once related. “That’s the way Walter Brown was.”

A person of many talents, Brown also founded a popular professional ice skating show called the Ice Capades and served as president of Boston Garden from 1941 until his untimely death by a heart attack in 1964. But what Brown is most remembered for today is his stewardship over the Celtics, which became one of the greatest dynasties in all of professional sports under his watch, winning the first seven of the franchise’s 17 NBA championships. These were the team’s glory days when Hall of Fame talents like Russell, Bob Cousy, Tommy Heinsohn, Bill Sharman, Sam Jones and John Havlicek graced the parquet floor in the old Garden with their hoop magic. “Brown impressed me immediately as a down-to-earth guy,” wrote Havlicek in his 1977 autobiography “Hondo: Celtic Man in Motion” with Bob Ryan. “He didn’t go around waving a diamond ring in people’s faces, or anything like that. He had a reputation as an individual who never went back on his word. He liked to do business with a handshake.”

Brown was able to accomplish all this despite lacking substantial financial means. He instead opted to rely on his own wits, creative talents and good character to keep the Celtics afloat even if this meant taking out a second mortgage on his house when the team looked like it was heading for bankruptcy in the late 1940s. “He was prepared to put everything he had into the Celtics because he believed in them,” his wife Marjorie remembered.

'The key to being a true Celtic, if there is one thing, is you have to be a man and accept responsibility for your actions,' Boston center Bill Russell once related. 'That’s the way Walter Brown was.'

Brown was by no means perfect. His temper could get the best of him at times but such ire was usually short-lived and easily forgiven. A case in point was 11-time champion Bill Russell’s rookie year when Brown grew particularly incensed after a close regular season loss to the Syracuse Nationals, the forerunner to today’s Philadelphia 76ers. “You bunch of chokers!” he yelled at his team. “I’ll never come into this dressing room again.” The next day a visibly contrite Brown addressed his players as they were getting ready for practice. “I’m sorry,” he said as he absent-mindedly kicked the floor with his foot. “I’m just a fan, and I was so scared we were going to lose again that I got frustrated. I didn’t mean what I said. I was upset. I apologize.”

Russell, for one, came away impressed by the entire episode. “[Brown] owned the team,” he said. “He didn’t have to say that. But that’s the way he was, a decent human being, and he’ll always have the hearts of the guys who played for him.”

The same cannot be said of Donald Sterling.

Related: