Advertisement

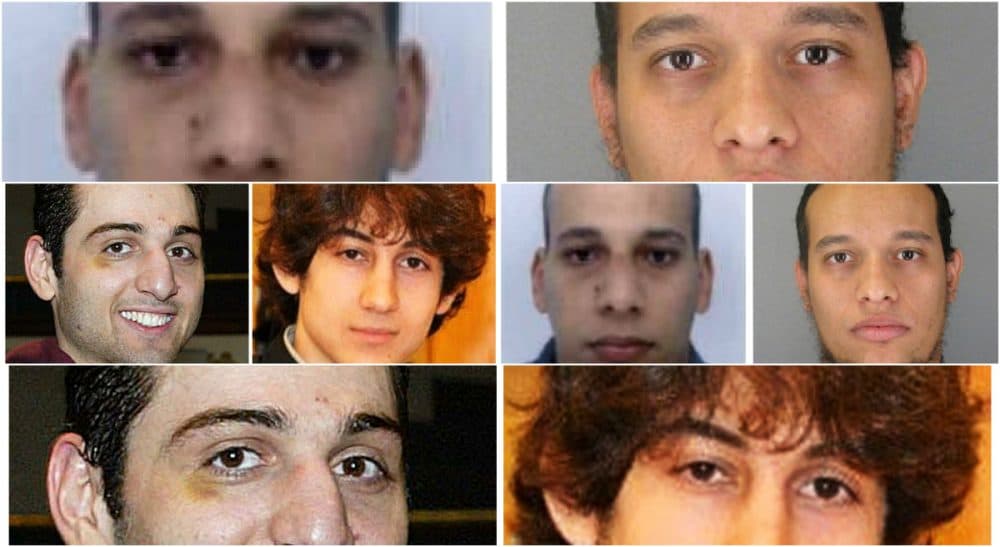

Children Of Conflict: The Alleged Terrorism Of The Brothers Tsarnaev And Kouachi

Experts say the people who join Islamist terrorist organizations such as al Qaeda long to be part of something greater than themselves, fulfilling what they believe to be the wishes of the prophet Mohammed. A precise profile of individual terrorists is harder to draw. Some are college graduates, others are high school dropouts, some are true believers, others are sociopaths. Comparing the backgrounds of the brothers Tsarnaev in Boston and the brothers Kouachi in Paris provides insight into intergenerational trauma, which is not to excuse their alleged violence, but to explore its many layers.

Said and Cherif Kouachi were born in Paris, in 1980 and 1982, to parents from Algeria who likely experienced firsthand their country’s war of independence from France between 1954 and 1962. It was a bitter conflict between the mostly Muslim population and the French military, which led to independence, but divided the country and left more than a million people dead.

Comparing [their] backgrounds ... provides insight into intergenerational trauma, which is not to excuse their alleged violence, but to explore its many layers.

Ethnic Chechens Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were born in 1986 and 1993, far outside of Chechnya. Alice LoCicero, a psychologist and author of a recent book, “Why ‘Good Kids’ Turn into Deadly Terrorists,” believes the Tsarnaev family trauma began in 1944 when the grandfather was forced to leave Chechnya after Stalin took over the country and deported 400,000 Chechens, with as many as half dying within the first year. In 1991, the failed First Chechen War for independence began as the Soviet Union disintegrated. Even in their adopted home of Kyrgyzstan, Anzor, the Tsarnaev brothers' father, was forced out of his job for being Chechen, and some accounts indicate that both he and Tamerlan were beaten on the street. The Tsarnaev’s family dog was beheaded as a warning that the family was not wanted there when Dzhokhar was 6-years-old. The family moved to the Republic of Dagestan, but the Second Chechen War followed them.

British psychologist Ed Cairns, who researched the effects of war on children in Northern Ireland, described political violence as one group using violence to influence power over another group. Children, he suggested, can absorb and interpret the trauma suffered by their parents. "The trauma of political violence experienced in one generation can ‘pass’ to another that did not directly experience it,” wrote Kaethe Weingarten, Ph.D., an associate clinical professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, in a 2004 journal article.

Psychologists have seen trauma manifested in the children of Vietnam veterans, Holocaust survivors and the descendants of African American slaves. Children witness the emotional disturbances, regret, worry, shame and humiliation of their elders through stories, behavior and even, silence. Some children may be unaware of how they have internalized the trauma. Others may feel the need to set things right by supporting various causes, becoming politically active or joining a military organization. Certainly, few resort to terrorism.

Many would argue that the U.S. and French governments did what they could to support the fragile Tsarnaev and Kouachi families. Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s father received asylum in the U.S. and the family benefited from state assistance as the parents established themselves and adjusted to their new country. The parents of the Kouachi brothers died when the boys were 12 and 14, the teens were raised in a government-funded children's home in central France. Despite such safety nets, both bands of brothers lost parental support and guidance as they were establishing mature identities. The Tsarnaevs’ parents split up and left the United States. French social services released the Kouachi boys from care when they became adults.

Both sets of brothers lived together as young adults when, according to reports, the older brothers, Said Kouachi and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, became increasingly interested in jihad and shared their convictions with their younger brothers. Three years apart, the Tsarnaev brothers in Boston and the Kouachi brothers in Paris allegedly planned their respective missions and procured or made their weapons, relying upon one another to perform acts of murder and hostage taking before seeking escape; they acted as family cells.

In this technological age, these brothers demonstrate how the personal is political and the political personal.

The Kouachi brothers were more militarized, having spent time with al Qaeda in Iraq and Yemen. In a telephone call with a French journalist during the siege, Cherif Kouachi said he targeted Westerners “who are killing children in Iraq, Afghanistan and in Syria.” His comment suggests that he may have been more emotionally motivated by the West’s “collateral damage” — the unintentional death of innocents — than by the political goals of the organization that he said sent him, al Qaeda in Yemen.

His justification echoes a note allegedly left in the boat where Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was found hiding from police after the Boston Marathon bombing, which said, “The US Government is killing our innocent civilians.” Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has pleaded not guilty to all charges against him.

In this technological age, these brothers demonstrate how the personal is political and the political personal. They may have experienced the West’s air strikes as an unbearable reminder of the deep humiliation and suffering felt by their loved ones in different countries decades earlier. Although these bands of brothers have allegedly maimed, killed and psychologically hurt countless people, they have also warned us to pay close attention to the children of conflict. Although wars seem to end, their legacy may linger in generations to come.