Advertisement

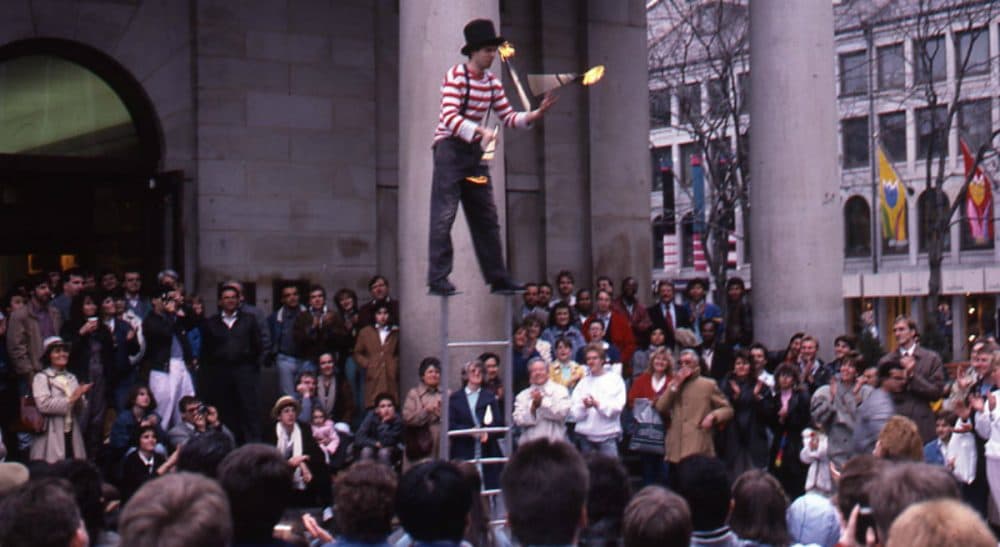

Soaking The Buskers Of Faneuil Hall

We will never hear “The Lighthouse Tragedy.” According to the poem’s author, this is probably for the best. Benjamin Franklin was only 12 or 13 years old when he penned his lament for the drowning of a lighthouse keeper and his daughters on Beacon Island, now Little Brewster Island, in the outer reaches of Boston Harbor. “It was wretched stuff, in the Grub-street-ballad style,” he wrote in his "Autobiography," but he performed the piece in the streets of the city, where prints of the text nonetheless “sold wonderfully.”

The elder Franklin didn’t see much future in busking, though. “Verse-makers were generally beggars,” father supposedly told son.

Times must have changed because today the directors of a $10 billion real estate giant, Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp., insist that Boston’s street performers are in a position to give back.

To suggest that buskers, whose hard work ensures much of Faneuil Hall’s appeal, are freeloading is not just wrong but insulting.

The company, which manages the Faneuil Hall Marketplace, is demanding that artists there pay between $500 and $2,500 for the privilege of earning tips and vending small wares. The artists are not happy. It is the latest sign of tensions between Ashkenazy and the buskers, who are vetted in auditions and already follow rules regulating noise and location. Last summer, the company attempted to ban variety acts using amplification, leading to an acrimonious response from performers and eventual compromise. And, speaking on background, one busker told me that off-season meetings between performers and the property manager have ceased.

Given the apparent lack of communication between the company and performers, the justifications it has offered are unsurprisingly spare and confusing.

The company claims “there are significant costs associated with hosting an entertainment program including administration, promotion, scheduling, and security,” but two performers who spoke on background told me they had little contact with administration. One said the company was demanding payment to offset the cost of security guards and social media promotions performers had not requested. While the company suggests that it and its predecessors — Ashkenazy took over the Faneuil Hall lease in 2011 — have always paid these costs, another performer said he detected no increase in security personnel that might necessitate greater outlays.

And promotion hardly seems valuable to the performers. Faneuil Hall is the world’s seventh-most popular tourist attraction, garnering some 18 million visitors each year. With that much foot traffic, what good is a tweet?

Advertisement

But the decision is not only hard to grasp. It also comes wrapped in a, frankly, oblivious appeal, suggesting that management has failed to understand the operations of the very business it runs. “For the past 39 years, Faneuil Hall Marketplace has supported the program in its entirety and paid all the costs without any contributions from performers,” management asserts. Hardly.

Performers contribute almost everything that makes entertainment at Faneuil Hall possible. They contribute their time, equipment and skilled labor in exchange for tips. Neither management nor tenant businesses compensate them, yet both benefit from the customers buskers draw. These customers shop in tenants’ stores, furnishing rent checks for the property manager. To suggest that buskers, whose hard work ensures much of Faneuil Hall’s appeal, are freeloading is not just wrong but insulting.

Such ill treatment is hardly novel for Boston-area street artists, who have put up with a lot over the years, from confusing permitting rules to unlawful evictions to official distractions, such as Christmas music played in subway lines. In 1989, Gov. Michael Dukakis, who had started the first subway music program in 1977, acknowledged that hardship, which he described as a “mistake.”

At times, businesses, municipalities and the MBTA have supported the buskers. At other times, they have thumbed their noses, enacting severe restrictions on performance without performer input. This despite apparent community interest. For instance, in 2003, the T attempted to impose new rules without consulting artists licensed to perform, leading to protests, arrests, a petition whose organizers claimed 16,000 signatures, and eventual compromise. The pattern repeats. Officials change the agreed-upon rules by fiat, failing to recognize artists’ legitimate concerns, only to find those artists responding with reasonable proposals that enjoy public backing.

And yet, over time, busking opponents seem to have the upper hand. Harvard Square — which once thrived on street music, puppetry, dance, clowning, juggling, painting and other talents — has gone tame, with designer stores and restaurants catering to the happily domesticated and almost nothing out of doors for the weirdos or your average family with kids. Such activities now come occasionally and fully disciplined, behind the metal barricades assembled for sanctioned street fairs.

Buskers are hardly unified in their opinions on these matters. Some chafe at any official restriction on what they see as free expression in public. Others appreciate a public interest in some control — beyond their internal etiquette — but want to be consulted and speak their minds when outsiders seek new limits.

the effect of such extreme fees ... will be to dissolve the wit and spontaneity performers bring to a historic, communal place, solidifying its metamorphosis into yet another consumer citadel, indistinguishable from the rest.

At Faneuil Hall, those limits are primed to expand. That a $10 billion company wants to soak performers for a few grand a year suggests the plan has less to do with money — at least, today’s money — than with a longer-term vision of the marketplace’s character, especially of who is to populate it. Perhaps the management wants a tidy mall, free of those street people.

Or perhaps there is no grand plan. Maybe it’s simple malice. Or incompetence. Or something else entirely. Ashkenazy’s statements, again, are inscrutable. Whatever the motive, the effect of such extreme fees — Cambridge charges only $40 per year for its permits — will be to dissolve the wit and spontaneity performers bring to a historic, communal place, solidifying its metamorphosis into yet another consumer citadel, indistinguishable from the rest.

But if the past is a guide, the performers of Faneuil Hall will get organized. They will make a strong case. And they just may secure the compromise that should have been offered from the start.