Advertisement

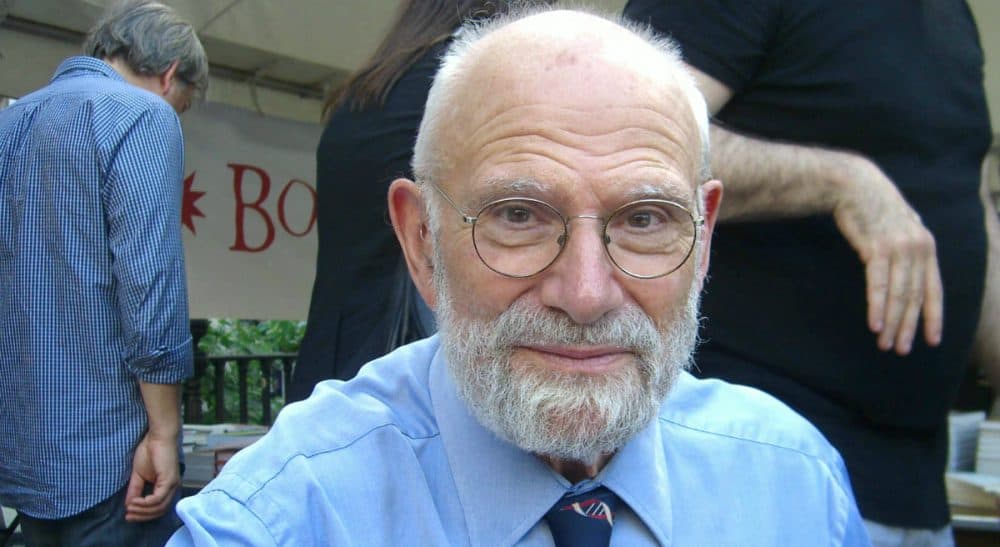

Oliver Sacks Couldn’t Cure Me, But He Gave Me So Much More

On Sunday, Oliver Sacks' obituary in The New York Times was the first thing I read when I woke up — still in bed, on the bright light of my phone. He had a tumor in his eye, found and treated nine years ago, that recently metastasized in his liver. He was 82, and knew he was dying. He had written about the resurgence of cancer, and how he felt about what would happen next, a number of times since February, when he got his diagnosis.

in the times that I met him, almost a decade ago, he profoundly touched my life, and my career.

There have already been many articles about the life and legacy of Dr. Sacks published since his death; just 12 hours ago as I write this. I’ve been reading them quickly, greedily. I wish there were more. I won’t recount the many things he accomplished — the books and articles he wrote, the patients he helped, his work demystifying the confusing and contradictory malfunctions of the human body and brain. He touched innumerable people in his life. He shaped the way we interpret both the medical literature and the narratives of those being treated. That story — his story — is one well covered, and not mine to tell.

Mine is a small story. I only met Dr. Sacks a few times. But in the times that I met him, almost a decade ago, he profoundly touched my life, and my career.

I had been in a car accident shortly after graduating from college. The accident fractured my pelvis, my sacrum, my skull; severed the ligaments in my left knee; and stole my sense of smell. I had wanted to be a chef, but without smell, I couldn’t tell if the food in my fridge was rotting, let alone sense the subtle variations of flavor. The familiar odors of my loved ones, of my favorite rooms and places, all were gone. I was 23 years old, and a recent transplant to New York City. Feeling distraught and alone, I turned naively to a man whom I had never met, but who I felt sure would have the answers that could help me regain my sense of smell. I wrote a letter to Dr. Sacks about my condition, printed it out, signed it, and mailed it to his office. I’d heard he didn’t use the Internet.

A few weeks later, to my surprise, I returned home to find a handwritten letter from this famous neurologist and world-renowned author in my mailbox, scrawling and thick, inviting me to meet. I was ecstatic. I was sure he would understand the loss of my sense of smell and what a recovery — or lack there of — would look like for me. After all, he was Oliver Sacks.

Advertisement

In the first five minutes of our first meeting, however, he told me — quietly, as we walked down the stairs at the Cornelia Street Café in Greenwich Village — that he didn’t know much of anything about smell, though he was “interested in learning more.” That scene, I’ll admit, is seared into my brain — the dusty stairs, the dark walls, the white mop of hair and slight British lilt — because I felt immediately devastated. I had hoped, deep in the place where 23-year-olds store the last vestiges of childlike hope, that Dr. Sacks would cure me. And if he couldn’t, I despaired, then no one could. I went home that evening feeling disappointed, and (sigh!) sure that this was the end.

A month later, however, he invited me back for another visit. Expectations rejiggered, I jumped at the chance. I met Dr. Sacks three more times in his office, a room filled with books and journals and knickknacks of all kinds. He didn’t seem to have an agenda, and neither did I. He gave me something far more important than answers — he gave me time, unhurried, generous amounts of time. I think back on that today — in a life that often feels far too busy to send that extra email, to answer the phone and talk instead of replying with a text, to take that intern out for coffee, to give freely when I don’t expect anything in return. His generosity was extreme. I was incredibly lucky.

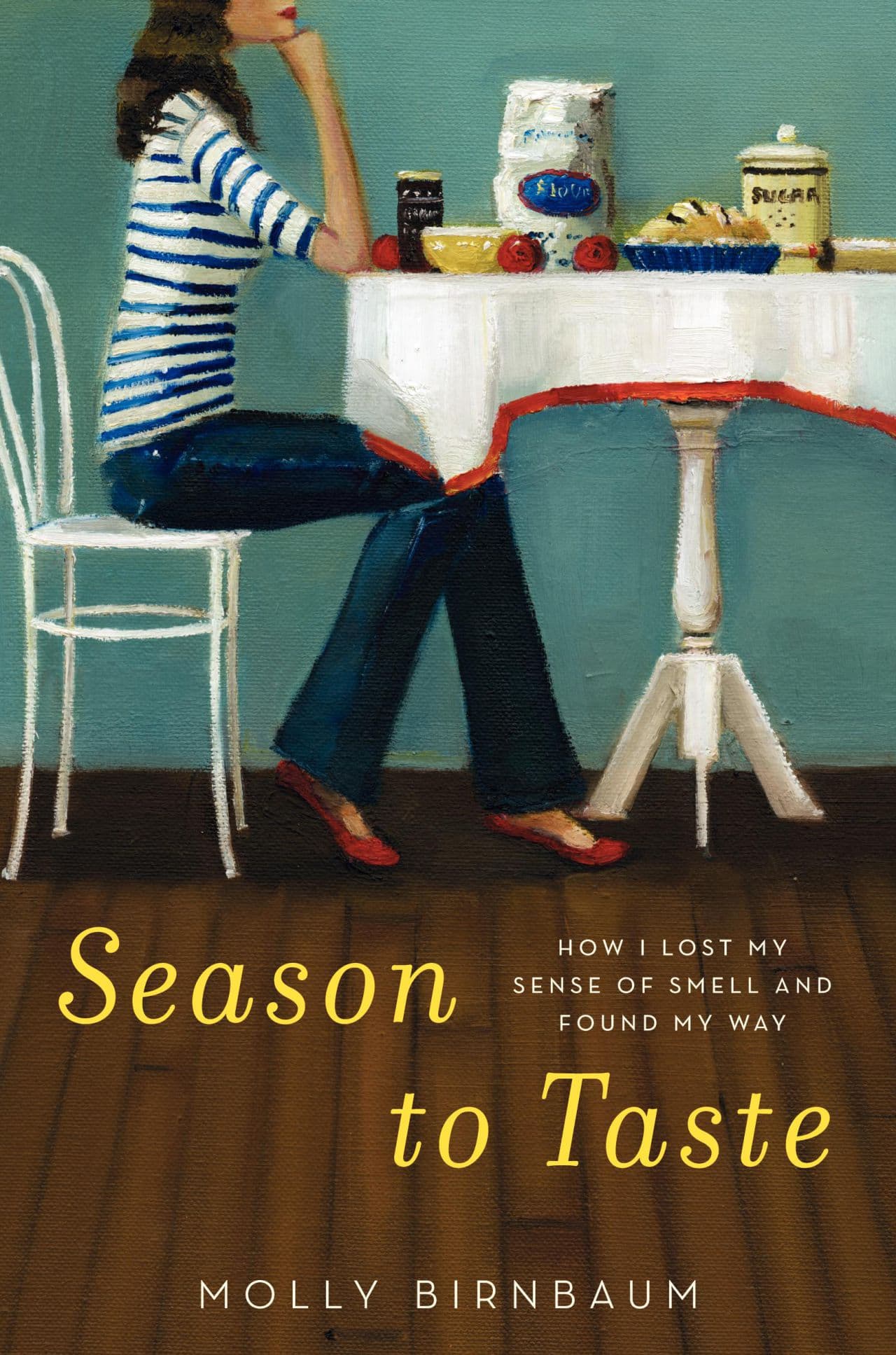

In those meetings, we spoke about medical mysteries, what it means to be a patient and a journalist and both at the same time, how to make sense of the nonsensical. I took strength from his strength in not knowing answers. Soon, I began working on a book about my own experience. Dr. Sacks empowered me to go out and report, to look at myself with empathy, to find the thread of the story in what felt otherwise nonsensical and strange.

Dr. Sacks empowered me to go out and report, to look at myself with empathy, to find the thread of the story in what felt otherwise nonsensical and strange.

When I think about those years in New York today, I often gauge the time, and my recovery, with what happened in Dr. Sacks’ office. Last month, Dr. Sacks wrote in The New York Times about the process of dying, and the comfort he gets from the physical world around him — including the elements of the periodic table.

"And now, at this juncture, when death is no longer an abstract concept, but a presence — an all-too-close, not-to-be-denied presence — I am again surrounding myself, as I did when I was a boy, with metals and minerals, little emblems of eternity," he wrote.

His desk was covered in metals and minerals when I visited him, too. During one of our first meetings, he held a craggy, bright yellow rock under my nose and asked if I could identify it by smell. I inhaled and exhaled, slowly. I couldn't smell a thing. A year later, when I was just starting to feel like I might someday recover, he held it up again. I inhaled; I exhaled; I registered a pungent, biting aroma. It was sulfur. Periodic element 16. He asked me what it smelled like. "A volcano," I said.