Advertisement

Witnessing The Challenger Disaster: A Reporter's Notebook

It was my first visit ever to Florida and for days it had been cold. This was not the way I envisioned the Sunshine State in January.

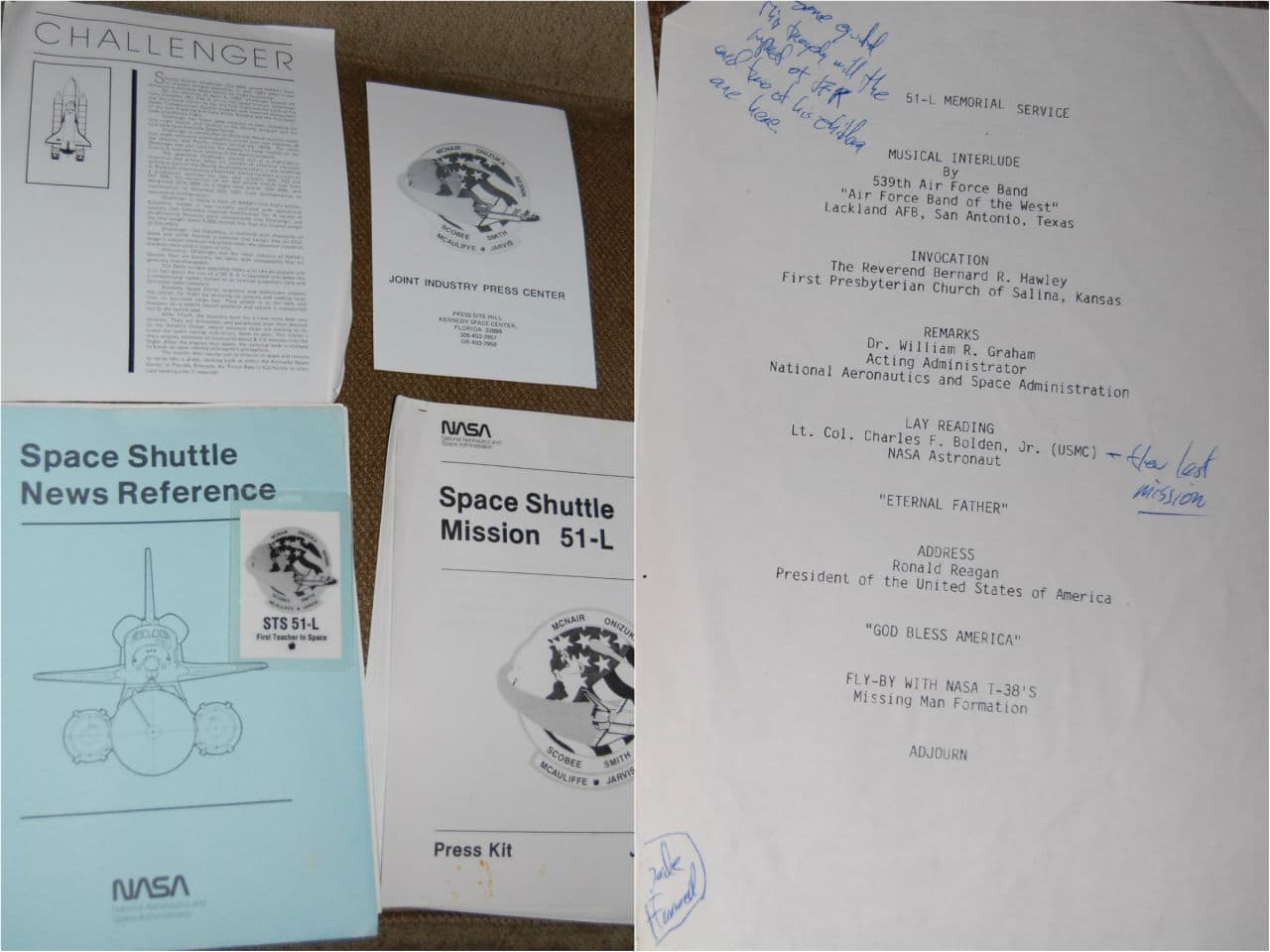

Due to the chill and other problems, the Space Shuttle Challenger launch had been delayed. Reporters, including yours truly, were vamping for days. With NASA postponing liftoff, we were talking and writing about the weather, the other issues with the flight and about any sidebar we could find.

Frankly, my editors were bored, as there was nothing new to report.

We would learn later that despite concerns from engineers, the shuttle was approved for launch.

Little did we know then what would come to pass, or that we would become experts on how cold weather affects solid rocket booster O-rings.

It was well below freezing the night before the launch. That morning, January 28, 1986, I arrived well before dawn, as I had early morning radio responsibilities. It was still below the freezing mark and there was ice all over the launch pad, icicles actually hung from railings.

Prior to liftoff, I had been outside speaking to family members and others who traveled to Florida with Christa McAuliffe. Christa, the Boston-born, graduate of Framingham State College was to be the first “Teacher in Space.” She taught high school history in Concord, New Hampshire. The Boston radio station I worked for at the time selected me for the Challenger assignment because I had worked in Concord for years. Though I never met Christa, I did know several people in her contingent.

Just before launch time, I slipped back inside a NASA building to broadcast. At roughly 11:38 a.m., the hold-down bolts were released as the Challenger slowly lifted off. I recall describing how the building wildly shook and rattled, and how the sound of the blast-off was nearly deafening even though the building was a mile from Launch Complex 39-B. The report was brief, and I was quickly off air.

Advertisement

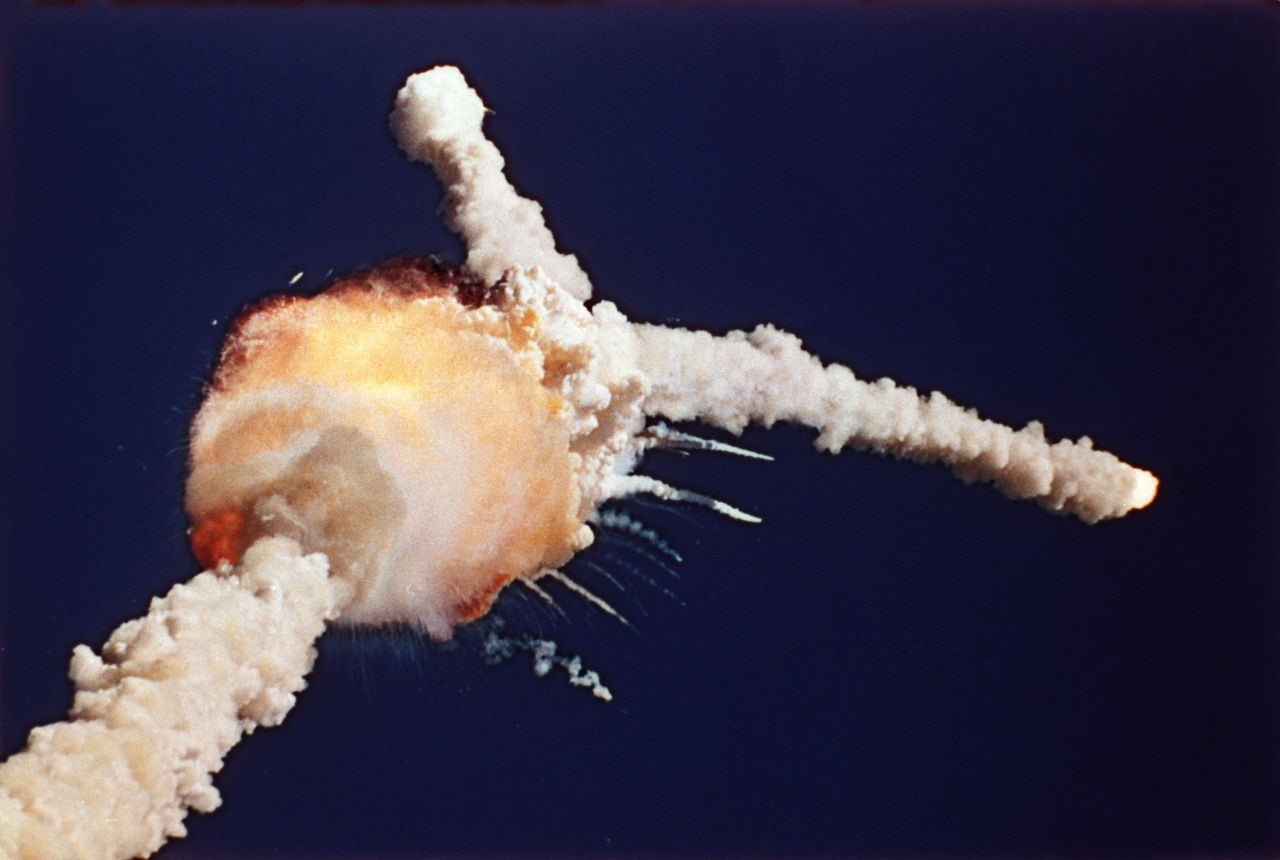

At roughly 58 seconds into the flight, as a tracking camera would later show, a plume began to appear through one the joints of the solid rocket booster, as an O-ring, which apparently failed to seal due to the cold temperatures, began to leak. At 73 seconds, there was a fireball, and the Challenger broke apart at 48,000 feet above the earth.

A short time later, I was back on the air beginning what would become my longest-ever radio monologue — around 45 minutes with no interruption. I described what had occurred, as best I knew it at that time — the problems that morning with the frigid weather, and a detailed recounting of the days of delays that preceded. I ad-libbed every word, used no notes.

I spent the rest of that day, and several more days, in that NASA building, chasing officials for scant details at impromptu briefings. I answered countless questions on the radio from colleagues back in Boston, especially about survivability for the astronauts. But, we all could see from the endlessly looping video, there was no chance of any controlled descent for the crew. And I knew from my earlier study of the NASA flight briefing book, that there was no escape system on the Challenger for this kind of disaster.

Days before the launch, I pored over the section on whether the crew would be able to escape if something went awry. Why I scrutinized this part of the book, I do not know.

We would later learn that despite the massive explosion, the astronaut crew cabin remained largely intact, and probably ascended to 65,000 feet in the air, before its long tumble to the ocean. NASA determined it was possible members of the crew survived the explosion, and found that several emergency oxygen packs on board were in-fact activated. But the cabin crashed into the water at around 200 miles per hour. No one could survive that kind of impact.

Three days later, I flew from Florida to the Johnson Space Center in Houston for a memorial service attended by President Reagan and thousands of NASA employees and guests. As we ascended to cruising altitude, 35,000 feet, I recall thinking of how excited McAuliffe and her colleagues must have been at this point in their flight, not knowing what was about to occur. It was the first moment my eyes welled up with tears.

Thirty years later, some of the events remain a blur — hazy snippets of memory. But other things, I recall in minute detail. The flight briefing book is one such example. Days before the launch, I pored over the section on whether the crew would be able to escape if something went awry. Why I scrutinized this part of the book, I do not know.

I have never covered another launch. I haven’t even been back to the Space Center as a tourist. I cannot bring myself to make the trip.

At home, there is a box I very rarely open. In it, is my NASA-issued shoulder patch for Flight STS-51-L, and that dog-eared NASA flight briefing book.

I think, today, I’ll bring them out into the light.