Advertisement

My Father, His PTSD, And Me

My father was the one who thought of daycare for our kitten. She’d be lonely on her own, he said, and the neighbors across the street had cats. To keep her from running back across the road, he put her in the car each morning and drove a mile, U-turned, and came back to the neighbors’ house. Dislocation complete. He was a force of kindness. When my sister or I was sick, he brought us slivered ice with ginger ale and read to us for hours. On wintry mornings he warmed our boots by the stove.

Once, when I asked, he told me he’d killed men in Korea. 'It was hell,' he said -- conversation over.

Then there was this: Never touch your father while he’s sleeping. We knew it had to do with The War, which wasn’t talked about in our house but which we understood was Korea. And this: On family trips to the beach, he drove with whiskey stashed beneath his seat. He sipped from it before we carried our towels and buckets down to the sand. My mother learned, if she wanted the day to go well, to say nothing.

Only later, after my parents’ divorce, after my sister and I were mostly grown, would we understand the signs of PTSD — my father gripped tight, and the rest of us in tow.

Before he got drafted, my dad was training for the Olympic time trials in cross-country skiing. In July 1952 he was sent to Korea as a tank crewman with the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division. The fighting on Old Baldy was bitter, hand-to-hand in the trenches with rifles and grenades. My father told us little of this. Most of what we know about his time in Korea, my sister and I have pieced together from research and newspaper clips. After he was discharged, he came home and took a job as hut master in Tuckerman’s Ravine. His friends from that time recall that he stayed in the White Mountains for months on end.

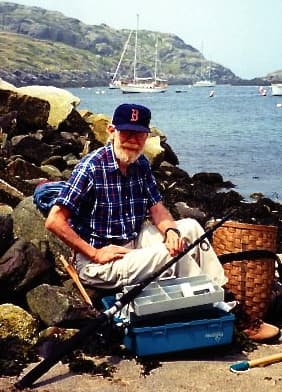

By the time he’d met and married my mother, and my sister and I were born, his life approximated convention. My mother recalls moodiness and insomnia, and times when he would disappear for whole days. But he held a job inspecting Maine’s state highways and taught skiing on weekends. Photos show him smiling, usually with an arm wrapped around my sister or me.

No one loved us more. When he and my mother separated, and she left to get her doctorate, my sister was eight and I was fourteen. We saw our mom on weekends, and my father assumed the role of single dad with grace: learned to cook, braided hair, chaperoned us to Brownies and gymnastics. I don’t mean he was saintly. Dishes piled up in the sink, and sometimes we missed school when he was too tired to get up. But he was the parent we relied on—the emotive, tuned-in one who asked, “How are you, pup?” and listened fully present as we answered. We learned confidence, a belief that we could go anywhere, do anything. He asked what we imagined being when we grew up. Lawyer? Oceanographer? Teacher? He was all about who we were going to be.

Who could he have been?

In the U.S., 18-22 veterans commit suicide every day. Many have PTSD. My father died a slower death over decades, a slipping away that led him in his sixties to abandon the house where we’d grown up. He just didn’t go home anymore, stayed in his camper or rented a motel room or came to visit us.

I wish we’d known better how to help. We staged an intervention for his drinking, insisted he seek counseling. Once, when I asked, he told me he’d killed men in Korea. “It was hell,” he said—conversation over. His resistance was a wall, and we pushed only so hard. It turns out that my sister and I are much like him: loving yet avoidant, tightly wound, night owls not entirely suited to the daytime world. Is it in our genes or learned? Secondary PTSD, trauma transferred to wives and children, is widely acknowledged in veteran support groups. Did this happen to us?

My father wouldn’t see it. In his eyes, my sister and I were perfect. He reveled in our careers and marriages, the grandchildren he adored. In his mind, we had succeeded—and so, by extension, had he. When he died 10 years ago, we scattered his ashes in Tuckerman’s, in view of the headwall he loved. He didn’t want a flag-draped casket.

He was all about who we were going to be. Who could he have been?

A few things remain of his time in Korea: his dress uniform with its stars and sergeant insignia, the Combat Infantry Badge, letters to his mother penned carefully to avoid mention of battle. I imagine him as she must have — a boy on a tank on a mountain road, rifle in hand, red hair barely visible from beneath his helmet.

And so it was. He didn’t talk about the war, didn’t keep in touch with the men he’d fought with, didn’t join the VFW or the Legion after discharge. He loved parades though, the patriotic marches, the ranks of vets filing by. When I was young, we’d play a game: How many times could we watch? After the parade went by, we’d jump in the car and race to another spot to view it again. And again. It was always the same — when the tail passed one last time, we drove to the playground by the river. I got on the whirl-a-wheel and my father spun it. Then I climbed off, dizzy and disoriented until finally the world righted and he was there, in the center, again.