Advertisement

Newton North High School: Talking To Students When A Symbol Of Racial Hatred Is Unfurled Close To Home

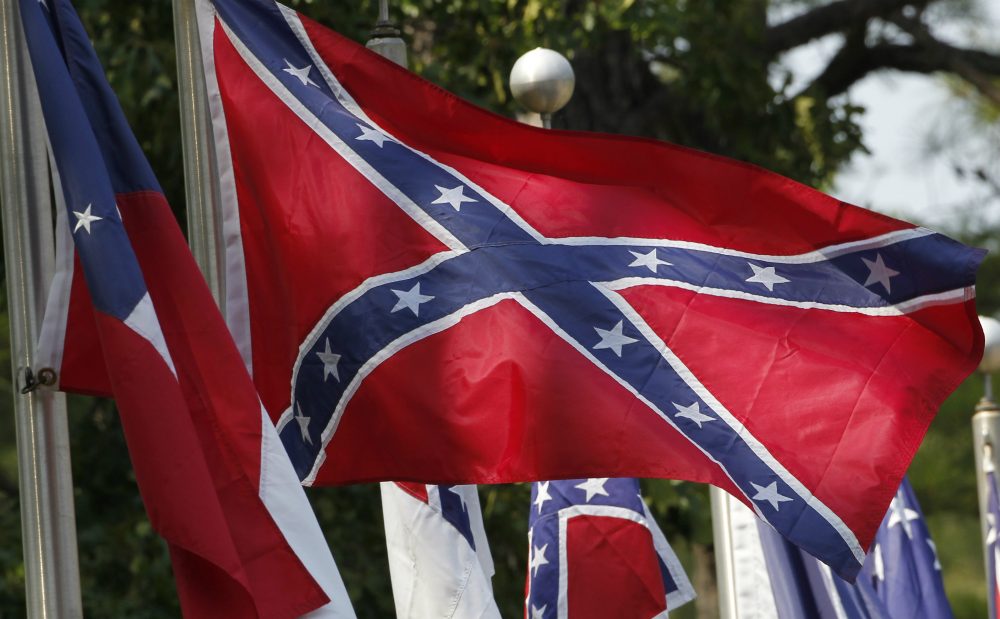

News last week that the Confederate flag, a symbol of both Southern heritage and racial hatred, was unfurled outside of Newton North High School brought my own experiences with flag-waving racists rushing back.

One of my greatest childhood shames is that, for a few years in middle school in the early '90s, I begged my parents to buy me a Bowery Boys T-shirt. The shirts — effectively a wearable Confederate flag — were extremely popular at my West Virginia school, and meant nothing more to me than a status symbol. I am forever grateful for my Indian immigrant parents' thrift, which proscribed brand name clothes and thus saved me from myself.

The flag unfurling at Newton North High School has reminded me that the Confederate flag is not just a Southern symbol, but a Northern one as well.

The rebel flag, as it was called where I grew up, was everywhere. Yet it wasn’t until high school that I was able to connect the ubiquity of the flag with the ubiquity of racial slurs that were flung at me on a regular basis.

A student in my shop class, often dressed in Bowery Boys garb, called me “sand n-----” and “camel jockey” every day for an entire school year. Parents of players on opposing teams screamed misidentified ethnic slurs at me during basketball games — anything from Speedy Gonzalez to Mr. Miyagi — and threw ice and garbage at me when I took the court. More times than I can count, I was approached by strangers in restaurants and parking lots who asked what tribe I was from, or where my papoose was. When I was 16 years old, two men drinking 40s while driving pulled up next to me at a gas station, took a long slug of beer, and then screamed, “Go back to where you came from!” In each instance, the flag was there — either literally, on a shirt or car bumper, or metaphorically, waving above the heads of the epithet-hurlers.

We didn’t learn about the Confederate flag in history classes in high school. We didn’t talk about its historical significance or its symbolism. Everything I know about the Confederate flag I learned through observation. And what I have learned, above all, is that my own history with this flag is insignificant when compared with the long record of racial violence committed against African-Americans under that flag in this country.

My own study of history taught me that marchers demanding voting rights on the road from Selma to Montgomery were met all along their route with white supremacists waving the Confederate flag. They were the ideological forebears of Dylann Roof, who posed with the Confederate flag multiple times before drawing his gun and murdering nine black parishioners at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Driving through the American South for six weeks this summer, I learned that Mississippi is the only state in the union still to feature a Confederate flag on its state flag. Its presence there has survived not one, but two, statewide referenda, even as it waves over places like Sunflower County, where 73 percent of the residents are black, and the poverty rate is 36 percent, or triple the national average. And at a Donald Trump rally in the bordering state of Florida, the Confederate flag waved for a presidential pretender who invokes racial hatred, calling people of color rapists, drug dealers and terrorists.

Now, the flag unfurling at Newton North High School has reminded me that the Confederate flag is not just a Southern symbol, but a Northern one as well.

As a middle school civics teacher, my instinct is to give young people lots of opportunities to make amends when they mess up. So even as I feel my own rage and anxiety triggered by this incident, even as the traumatized part of me wants to vilify the young people who brandished that flag, I am working hard to think about how this could have happened, and why.

This is not just a Newton North problem; this is a national problem...

We talk about white supremacists as a fringe group, significantly more visible during this presidential election, but we don’t talk enough about white supremacy, and how it serves as the foundation for our nation, whose economic power is predicated on a legacy of enslavement. We don’t talk enough about how we have repeatedly replaced systems of subjugation in our country — from slavery to sharecropping to convict leasing to mass incarceration — that ensure the continued dominance of wealth and whiteness. We don’t talk enough about the symbols of supremacy, and the feelings that they evoke, not just for the flag wavers, some of whom may see it as their heritage, but also for those at whom the flag is waved. We don’t talk about these issues enough as adults, which means that young people are left to make meaning on their own. Often, then, they end up making the wrong meaning.

The easy way out of the situation at Newton North is to put the onus on the school for addressing the issue in its classrooms. But a conversation in classrooms that isn’t followed by one at dinner tables and in living rooms is not sufficient. This is not just a Newton North problem; this is a national problem, and one that we will only solve by being honest about both our historical and present-day struggle against racial injustice.