Advertisement

That '70s Show: America's Energy Crisis Then, And Now

COMMENTARY

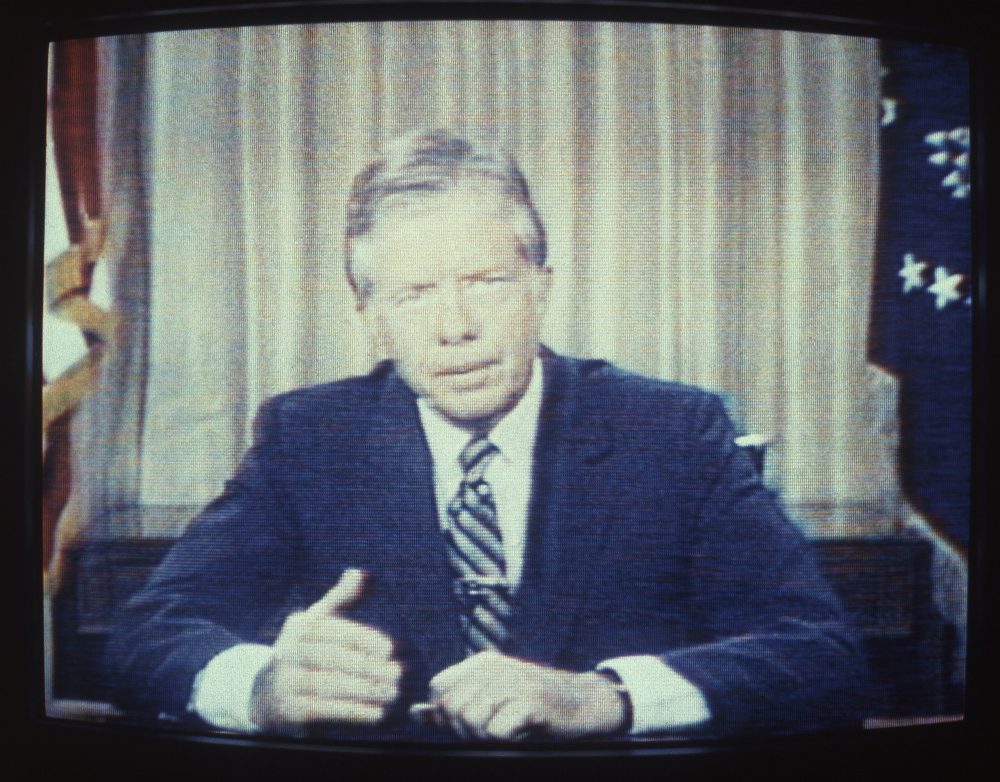

Almost exactly 40 years have passed since Jimmy Carter put on his beige cardigan and went on national television to speak about energy. He had just taken office, and the United States was in the depths of a years-long energy crisis triggered by the Arab oil embargo of 1973. Echoes of Carter’s fireside chat resound these four decades hence as a new administration assumes power — an administration that is overtly hostile to the Department of Energy, the inception of which Carter announced that winter evening in 1977.

The challenge Carter faced of overhauling the nation’s energy policy parallels the task of transforming today’s energy economy. The central problem in the 1970’s was a geopolitically fraught overdependence on foreign oil. In 2017, as the repercussions of climate change unfold, the country must undertake an epic transition from fossil fuels to carbon-free energy. The prevailing circumstances in Carter’s day were very different from those now, but the pertinent policy prescriptions and economic considerations then and now are remarkably similar, as are the political forces aligned to oppose any threat to the status quo.

As in Carter’s day, contemporary resistance to conservation stems from a fear that any cutbacks will stunt economic growth.

Carter was an early proponent of renewable energy. In a symbolic gesture, he famously ordered the installation of a solar hot water system on the roof of the White House. He believed sincerely in solar technology because it harnessed a cheap, embargo-proof, non-depletable source of energy, and he called on the nation to develop it aggressively. His bullish stance on solar power in 1979 anticipated its growing importance in the present-day energy mix.

Carter was equally prescient about employing taxation as a means to discourage the use of fossil fuels. He proposed a 50-cents-per-gallon “stand-by” tax on gasoline, to be phased in as fuel consumption rose above predetermined thresholds — a plan that Congress promptly rejected. But today, policymakers around the world are experimenting with carbon taxes to drive down the use of fossil fuels and capture their hidden social and environmental costs.

The gasoline tax proposal was part of a broad effort to promote conservation, a cornerstone of Carter’s energy policy. Besides the much-mocked admonishments to lower thermostats, his administration called for ambitious increases in fuel economy standards. Near the end of Carter’s term, the major auto manufacturers had acknowledged they could achieve at least 30 MPG by 1985, so a proposed requirement for 48 MPG by 1995 seemed realistic. But after Carter left office, the proposal was watered down, and fuel economy standards even now remain well within the comfort zone of the automakers.

Advertisement

Persuading Americans to conserve energy proved as difficult then as it does today. In a famous speech from April 1977, Carter, borrowing from William James, called solving the energy crisis “the moral equivalent of war.” He exhorted Americans to use less energy, and he warned of the consequences if they failed to change their lifestyle. Mirroring this rhetoric in a widely-read essay in the New Republic last summer, renowned climate activist Bill McKibben called for a wartime footing to battle climate change, noting the nation’s shared sacrifice and social cohesion during WWII.

As in Carter’s day, contemporary resistance to conservation stems from a fear that any cutbacks will stunt economic growth. Carter spoke to exactly that point in the “moral equivalent” address, arguing that an “effective conservation program will create hundreds of thousands of new jobs.” That same message resonates in Barack Obama’s recent op-ed in Science Magazine. Obama emphasizes the decoupling of carbon emissions and economic growth, i.e., the idea that economies can grow even as the adoption of renewable energy reduces the output of harmful emissions.

The secretary of energy has advocated the elimination of the Department of Energy. The administrator of the EPA is a lackey of the fossil fuel industry. The secretary of state is an oil mogul.

President Carter — having witnessed Ronald Reagan’s dismantling of his renewable energy programs in favor of promoting oil, gas and coal — must be troubled by the prospect of Obama’s climate initiatives meeting the same fate under Trump. The secretary of energy has advocated the elimination of the Department of Energy. The administrator of the EPA is a lackey of the fossil fuel industry. The secretary of state is an oil mogul.

And in that fireside chat 40 years ago, Carter said: “I realize that many of you have not believed that we really have an energy problem,” which brings to mind the pack of climate change deniers now getting settled in Washington. Carter’s agenda to move our energy economy toward efficiency and renewable sources remains unfinished, yet more urgent than ever.