Advertisement

Commentary

How Fiction Makes Real The Suffering Of Immigrants

Almost every American has an immigrant story. It may be his or her own — a narrative of persistence and hard work before claiming naturalized citizenship — or it may be passed down as family lore from ancestors past. For some families, the in-between of these stories — the cultural disorientation that strangers in a strange land face — appears only as a footnote. And for those of us who are generations removed from emigration, who speak the dominant language without hesitation, who navigate systems of government bureaucracy with relative ease, it is difficult to fully identify with those in the thick of cultural limbo without seeing the full picture, even as we sympathize with their plight.

Though news reports may remind us daily of the institutional indignities faced by members of immigrant communities both at home and abroad, a video clip or statistic is not enough to show us the full trajectory of lived experience. But deep reading, or what literary critic Frank Kermode calls “spiritual reading,” can stretch our empathy and understanding in ways that other media cannot. Three recent novels aim to do that by offering a glimpse into the daily lives of those who are driven by the desire to find true homes.

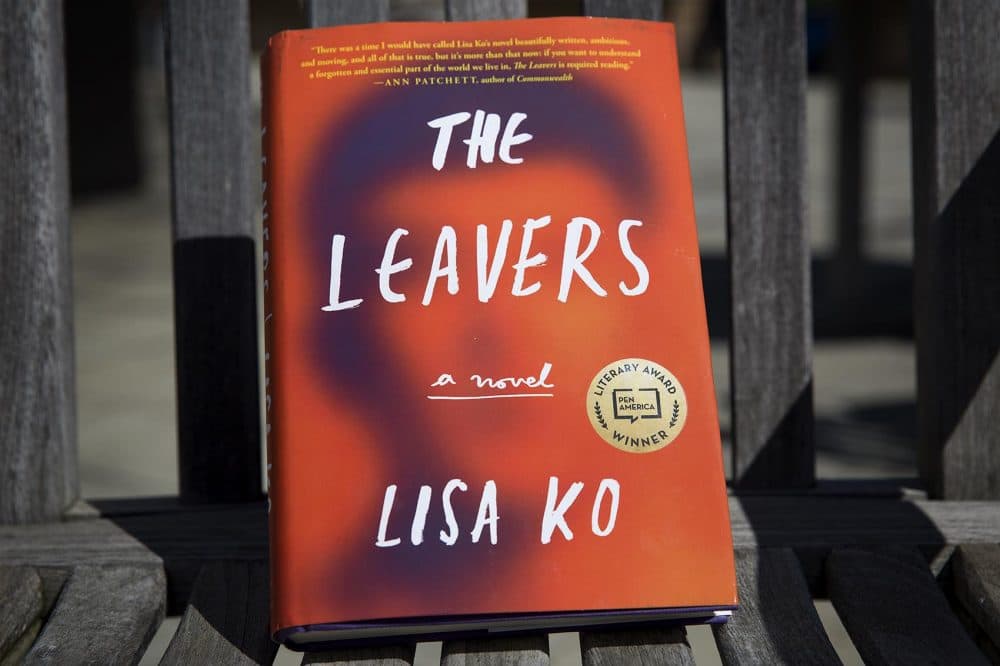

In Lisa Ko’s "The Leavers," a novel so prescient that it could be drawn from today’s headlines, we meet Deming Guo, an 11-year-old boy who lives in the Bronx with his mother Polly and their chosen family — her boyfriend; his sister, Vivian; and Vivian's son, Michael. The adults, Fuzhounese immigrants, work staggered shifts at nail salons and a meatpacking plant in a race to stay ahead of their expenses. For Deming’s mother, her American dream only goes as far as paying off the debt she incurred to allow for her passage to the U.S. When she is offered a chance to start over, with a job at a Florida restaurant, she dreams out loud as she shares the plan with her son. But they never move — at least not together.

It will be a decade until Deming, renamed Daniel by the couple who eventually adopts him, sees Polly again and learns that her leaving was not his fault, nor was it her choice. But in that decade — the in-between of not knowing — he inhabits a life that never truly fits because it denies half of his identity. And Polly, who is a world away when she hears of her son’s adoption, is devastated by the news and contemplates suicide. She later tells him, “You being gone like that, given over to another family like a stray dog, was too much to comprehend, and it hovered, like the rest of the world, just out of reach.” But find her he does, along with his first language and the country of his heritage and this belated reunification between mother and son allows Deming to finally realize a sense of home.

The desire to belong also permeates Min Jin Lee’s "Pachinko". The opening epigraph from Charles Dickens signals the thematic framework of this novel: “Home is a name, a word, it is a strong one; stronger than magician ever spoke, or spirit ever answered to, in the strongest conjuration.” Lee follows generations of a Korean family living under Japanese colonization as the relatives search to find a sense of belonging amidst a drive to survive. When young Sunja meets Koh Hansu, a handsome older man who travels between her coastal village of Busan, Korea and Osaka, Japan, she sees the possibility of a life beyond her town, one where choices need not be governed by utility. But as is often the case, reality does not match expectations. Sunja becomes pregnant with Hansu’s child and the implications of her choices ripple for decades.

[These novels] are about searching and finding, belonging and wanting -- the things that define our human experience regardless of our point of origin.

Nafkote Tamirat’s "The Parking Lot Attendant", set between Boston and an unnamed island where a colony of Ethiopian emigres have settled with the hopes of establishing an independent society, explores a similar quest. Like "The Leavers’" Deming, Tamirat’s unnamed female narrator is faced with the unexpected loss of a mother, leaving her yearning for a replacement. When the undiscerning girl captures the attention of Ayale, a parking lot attendant, and the unofficial leader of the Ethiopian community in Boston, she mistakes his interest for paternal affection until it is too late and she has been caught up in a multilayered scheme that threatens her own life.

One thread that unites these novels is the characters’ desires to belong — to a country, to a community, to a family. They are about searching and finding, belonging and wanting — the things that define our human experience regardless of our point of origin. Our experiences may be far afield from the landscapes drawn by these three authors, but they show us the full picture: The struggles are the story, not the parenthetical asides. As Karen Swallow Prior writes, “The power of ‘spiritual reading’ is its ability to transcend the immediacy of the material, the moment, or even the moral choice at hand … such reading doesn’t make us better so much as it makes us human.” And in doing so, it allows us to truly empathize.