Advertisement

Commentary

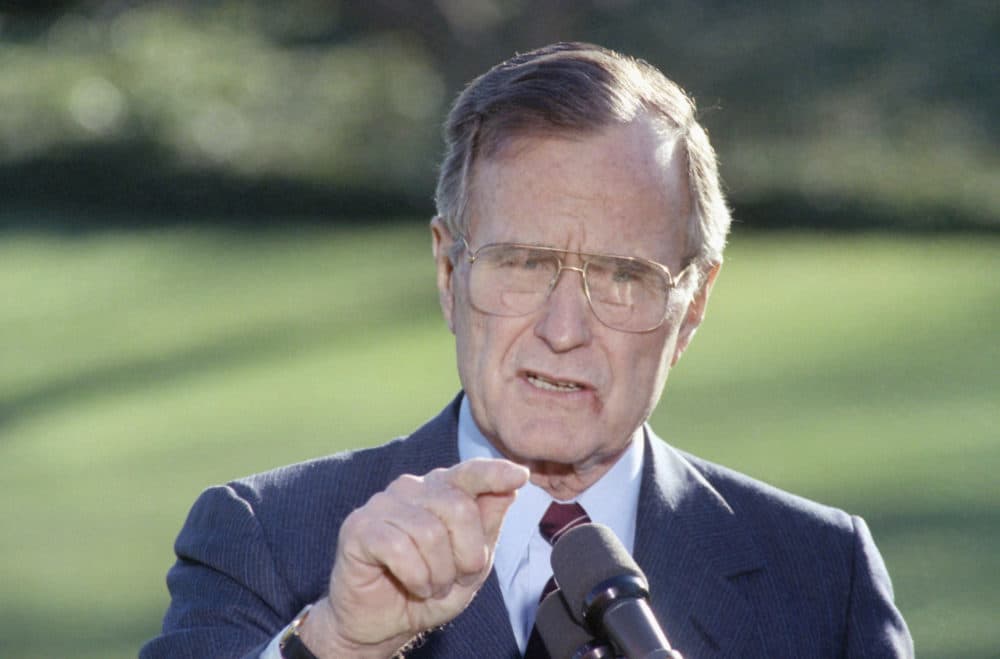

George H.W. Bush's Legacy Of Restraint

As the nation observes a four-day state funeral process that will culminate in President George H.W. Bush being laid to rest next to his wife, Barbara, and daughter, Robin, on the grounds of his presidential library at Texas A&M University, his legacy is being lauded for its civility and competence. Inherent in much of this commentary is some nostalgia given the current political strife in the nation and a dearth of decorum and humility at the highest levels of the executive branch.

The scope of President Bush’s lifelong public service was breathtaking. And his masterful presidential management of the Soviet Union’s rapid unraveling changed the trajectory of modern history.

Yet, perhaps the most significant decision he made as president was to resist the hue and cry to depose Saddam Hussein after the U.S.-led coalition drove Iraqi forces from Kuwait in the seven-month Gulf War. This choice solidified a decade of unchallenged U.S. hegemony in foreign affairs, until the decision was effectively reversed by Bush’s own son, President George W. Bush.

Bush tapped the personal relationships made over a lifetime of leadership and service to forge a stunning coalition to reverse Hussein’s sudden control of 20 percent of the world’s oil reserves. The U.S. created this alliance under the rubric of multiple U.N. Security Council resolutions that ultimately approved the use of force against Iraqi fighters in Kuwait. Bush expended major political capital in the effort. He took seriously the U.S. leadership role in the framework of the international community and worked within its norms to respond to Hussein’s aggression.

As a result, the Soviet Union ended up endorsing the effort, and China abstained — but did not oppose — the resolution authorizing force. On the battlefield, Syrian and Egyptian tank divisions fought alongside U.S. units, and Japan, Germany, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States bankrolled much of the coalition during the brief but resource-intensive war.

Bush adhered closely to the strictures of the U.N. resolution that his administration had meticulously negotiated. When its goals were met, he withdrew U.S. forces despite heavy pressure from political critics in the U.S. to "finish the job" and march to Baghdad.

The temptation to do more, of course, was present.

The U.S.-led coalition had degraded the world’s fourth-largest army within months and sustained a relatively minimal level of casualties. Bush had flexed the military might that President Ronald Reagan had rebuilt, the U.S. had roughly half a million troops in place, and Iraq did not have the means to stop a U.S. assault.

Advertisement

Yet, Bush did not betray his respect for the institutions and alliances that the U.S. led. He understood the decision wasn’t about him and his ego as president, but about the nation’s standing in the world. Bush projected the substantial power of the office he temporarily occupied by realizing the limits of America’s power and working with allies within international regimes. This was a far cry from his son’s tragic “you’re either with us or with the enemy…” mantra a decade later.

He understood the decision wasn’t about him and his ego as president, but about the nation’s standing in the world.

The Bush administration concluded that deposing Saddam Hussein would have wrecked the coalition, leaving the U.S. mostly on its own to eventually occupy Iraq — an outcome that was beyond any imagined mandate in 1991. Such a decision would have also profoundly complicated U.S. relations with a teetering and unpredictable Soviet Union, potentially undermining Mikhail Gorbachev and encouraging Soviet hardliners. It would have also helped further the malignant Iranian influence in the region.

Historical hindsight magnifies the quality of Bush’s principled decision to stand by his alliance and the U.N. resolutions. Bush did not have the experience set we have today to aid his decision making. He couldn’t yet see first-hand the cost in thousands of U.S. lives and trillions of dollars that an occupation of Iraq would entail. He hadn’t lived through the chaos of a power vacuum and the disintegration of Iraqi society and institutions, and the resulting rise of ISIS. Bush also hadn’t yet seen how chaos in Iraq could spread to neighbors, such as Syria, and enable Russia to gain a strategic foothold in the Middle East.

No, the Bush administration in 1991 wasn’t blinded by the hubris of its leader and didn’t have to experience such debacles to know enough to avoid foisting them on the nation and the world.

In this challenging political moment, it’s worthwhile to briefly contemplate Bush’s decision not to invade Iraq in order to keep some of the lessons from his humble and principled approach to foreign policy alive long after the coverage of his state funeral ends.