Advertisement

Commentary

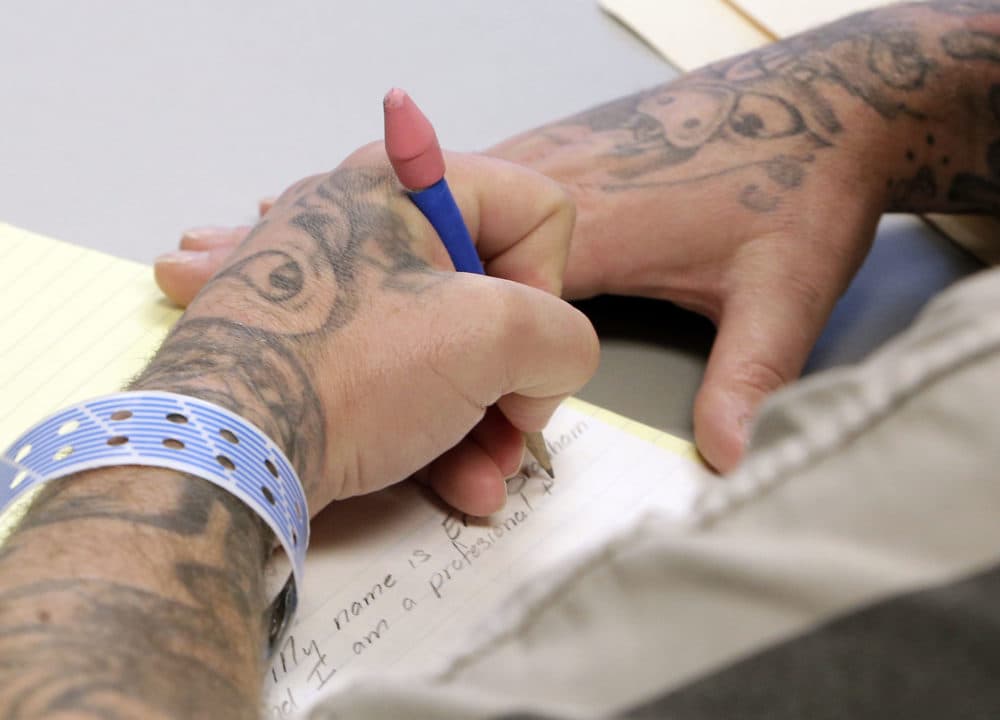

I Told Stories For A Living. Now I Help Prisoners Tell Their Own

I’m no expert on education programs in the prisons. I’ve been volunteering for just one semester. I’ve worked with 16 students in one class. The class, part of a degree program at a local college, requires the students to prepare and deliver speeches, and I help them with that preparation. With their fellow students, I critique the speeches as they develop.

I decided to volunteer in the education program at a medium security prison, because, as a recent retiree, I had the time, and because I wanted to do something that might make me uncomfortable. (I’d never been inside a prison.)

During the years when I was a professor at a different nearby university, I’d put off working in the its prison program, which was supervised by a friend. He’d urged me to participate. I didn’t. Better a late acknowledgement of his good work than none at all, I figured. Beyond that, I thought working directly with people who were incarcerated would be a way to live my politics. I wouldn’t just write my representatives. I’d make myself available to people who’d been crunched by the system, thereby not only doing some good (I hoped) but also learning about the justice and penal systems by meeting people who’ve been directly involved.

The young and not-so-young men in my class are intelligent and thoughtful guys. They are exceptionally supportive of one another and grateful for the time and energy donated by the people who come to work with them.

They laugh a lot. On my first day, one of the guys asked me if people ever recognized me by my voice (I hosted WBUR and NPR’s Only A Game for 25 years before retiring in 2018). I told him about having an early breakfast at a coffee shop in Chatham years ago. The cashier told me my voice was familiar, but said he couldn’t place it. I asked him if he listened to public radio.

“Why, sure!” he said. “You’re Ray Suarez!”

I told the men in my class that if I’d been quicker, I’d have said, “Yeah, I am. Now empty that register and tell ‘em Ray Suarez was here.”

When they gave their speeches, the students critiqued each other honestly and fairly. Nobody mocked anybody.

Everybody laughed, and then an inmate said, “Yeah, you’d done that, you’d be in here with us.”

I met with the students once a week for two hours and 45 minutes. Class couldn’t end early, even when we’d finished what we’d planned to do. The students couldn’t leave until “movement” was announced. Movement happened at 1:00, when they arrived in the classroom, and again at 3:45, when they returned to their cells.

Sometimes a guard sat in the class with us. Mostly he didn’t.

Late in one class when we had time to kill, we talked about the kinds of questions they would face when interviewing for jobs once they got out. I mentioned an old favorite — “Where do you see yourself in 10 years” — and I said that at 70, I figured the conservative answer might be “dead.” Everybody laughed then, too.

Before each class began, the students spent a few minutes catching up, as if they hadn’t seen each other in a while. It turned out that was the case. They came to class from several different cellblocks.

Advertisement

When they gave their speeches, the students critiqued each other honestly and fairly. Nobody mocked anybody. And no wonder. Their arguments were logical, persuasive and well presented. One guy made an excellent case for allowing men who’d been convicted of crimes to serve in the military, rather than spend years behind bars. Another argued that the justice system would work more effectively and more fairly if prosecutors were held responsible for their errors and oversights. After that presentation, a man serving a 55-year sentence gave the presenter a deep, bass “Amen.”

Then there was the guy who argued in favor of chocolate at every meal.

When one of the men in the class was released on parole during the semester, the others seemed genuinely happy for him. I didn’t hear any resentment, as in, “Why not me?”

At the end of the fall semester, the men got hold of a thank you card. My favorite message read in part as follows: “Thanx for all your insight. I appreciate the work you do. I hope you ain’t dead in 10 years.”