Advertisement

Commentary

Read Books With Your Children. The More Diverse The Better

In a throwback to my own bookish childhood, my second-grader is completely enamored of “The Babysitters Club” series, often requesting the faded paperbacks via inter-library loan and bemoaning the fact that I didn’t save my own original copies.

We were performing our usual bedtime routine recently: she reads on her own for a while, then my husband or I read a book out loud and chat with her before switching off the light. That night, she picked “Keep Out, Claudia!,” where Asian-American babysitter, Claudia Kishi, is turned down for babysitting by a family because of her race. It is a relatively progressive installment of the 1980s and 1990s series, which is set in a fairly homogeneous, fictional suburban Connecticut town.

Little kids are naturally inquisitive and don’t let injustices slide; my 8-year-old wanted to know why a family would treat Claudia that way. What followed was an important conversation about racism and prejudice. It unfolded in an organic, accessible way, driven by my daughter’s questions and rooted in a concrete example we could talk about with characters that meant something to her.

The benefits of reading aloud to our children are well known. For infants and very young children, it helps them learn how to speak and encourages bonding. For older children, who are independent readers, reading aloud encourages continued bonding and helps them make sense of their world.

According to the 2017 Scholastic Kids & Family Reading Report, 62 percent of surveyed parents of children aged 3 to 5, read aloud five to seven days a week — but the drop off is significant as children get older. Only 38 percent of parents read to their children aged 6 to 8, while just 17 percent of parents read to their children aged 9 to 11. This decline occurs at the same time children’s consciousness of the wider world grows sharper and more probing; when opportunities to answer questions and check in become more precious.

From fairy tales and parables to picture books and chapter series, stories have long been a fundamental way we introduce values and morals to children and foster empathy. It’s not just a question of reading aloud, then; what we read also matters. Given the rise in hate crimes over the past three years and the damaging rhetoric and polarizing policies that permeate the headlines and airwaves these days, empathy seems in short supply.

... children of all backgrounds benefit from seeing characters whose experiences are different from their own.

While the talk my daughter and I had about “Keep Out, Claudia!” was spontaneous, I’ve become a lot more intentional about the books we read and discuss together. I make sure she has agency in what she chooses to read, but is also exposed to more diverse choices and issues, from different religious and cultural traditions to stories of refugees and immigration.

Scholar Rudine Sims Bishop introduced the terms “windows” and “mirrors” to describe books in the early 1990s, and this frame remains incredibly useful in today’s climate. Books that are mirrors reflect back our own experiences and associations, while books that are windows give readers a view of a new perspective.

It’s important for children of color and other minorities to see representations of themselves in the books that they read. They need more mirrors. My daughter and other young readers — who are typically surrounded by people who look just like them and see similar experiences and characters in the books they read — need more windows.

Advertisement

Of course, scholars, librarians, teachers and advocates have long known this. They know that most importantly, children of all backgrounds benefit from seeing characters whose experiences are different from their own.

The growing #weneeddiversebooks movement casts as its mission “putting more books featuring diverse characters in the hands of all children,” and offers a comprehensive set of resources and recommended titles. Children don’t turn to books because they yearn for “teachable moments” or want a vocabulary to talk about injustice; they want to read a good story.

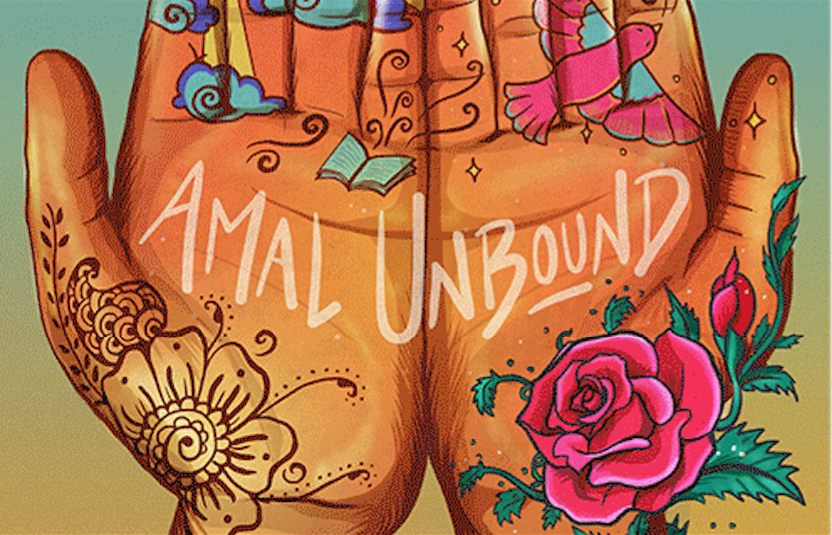

When my daughter spent the last night of our vacation staying up late to finish "Amal Unbound," Aisha Saeed’s bestselling novel about a young Pakistani girl’s experience with indentured servitude and her quest to return to school, it wasn’t because of the conversations about girls’ access to education it inevitably entailed. Rather, it was because the book is a richly detailed, engrossing story and she cared about Amal’s fate.

I recognize the inherent privilege I have in seeking out opportunities to tackle these topics with my daughter. So far, and unlike many children, her experiences with racism and bias have largely occurred within the pages of books, not in the real world.

Books aren’t the panacea for all that ails us, and conversations alone won’t solve the disparities in our world, but diverse books give parents a way to shape the conversation we have with our children about these issues, and they give children a natural entry point into an existing dialogue. It’s one we can’t afford not to have.