Advertisement

Commentary

The Brutality Of ‘Suicide Watch’

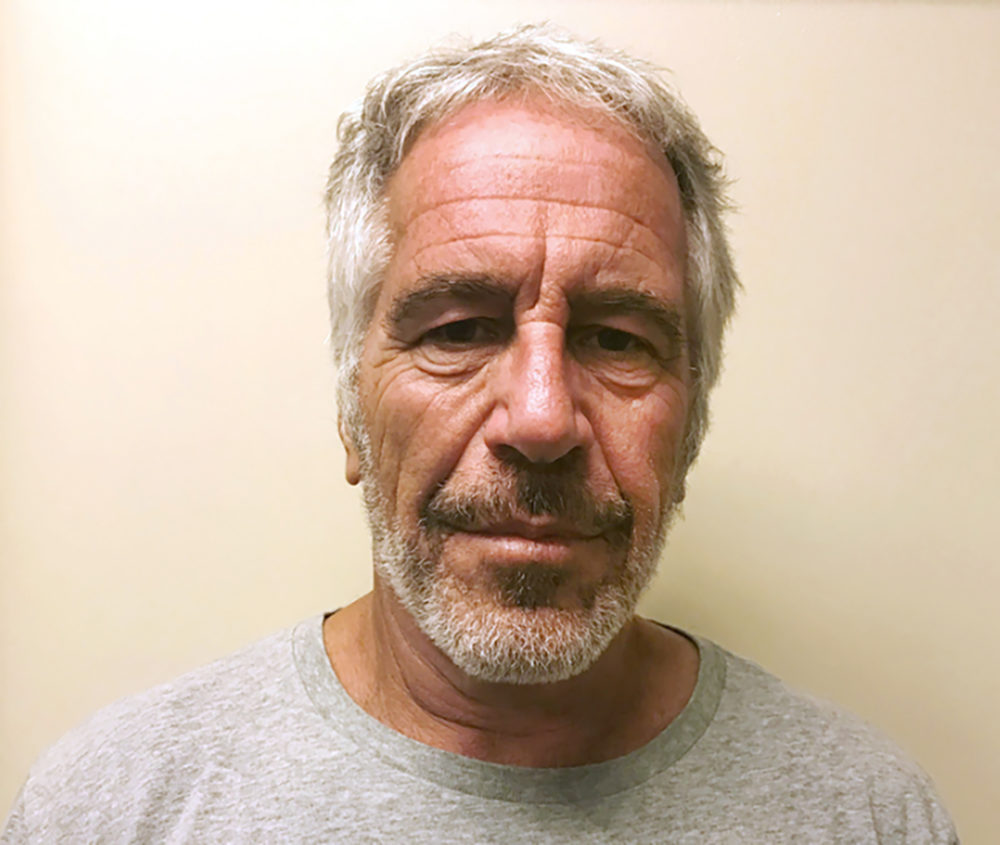

After Jeffrey Epstein’s death at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan, just a month after his arrest for serious charges of sex trafficking, two theories emerged. Some saw a murderous conspiracy to protect Epstein’s powerful friends from public exposure, and others saw a negligent correctional system that ignored obvious risks for suicide. In the latter camp, the loudest voices cried, “Why was he not placed on suicide watch in jail? It was predictable this would happen!” They assumed that the jail could have protected Epstein from himself, if only the proper supervision methods had been employed.

Technically, this is true. In my experience as a psychiatrist in jails and prisons, placing people on “suicide watch” — 24-7 monitoring by a corrections officer and/or surveillance camera — does make it much harder for them to harm themselves. It also makes it almost impossible to improve their underlying psychiatric problem. The conditions of confinement on “suicide watch” are harsh, and they bear little resemblance to bona fide psychiatric treatment. In many cases, they actually make mental health worse.

Even in the most sophisticated and well-staffed jails, suicidal people are treated with a distinct lack of compassion. They are stripped of their clothing and underwear and dressed in a smock made of a tear-resistant material that is similar to the blankets moving companies use to wrap furniture. Individuals are placed in a suicide-resistant cell — typically a single cell without bed rails or anything that a noose could be tied around — and offered no items of comfort. They cannot shower or shave, and sometimes they are not even given toilet paper for fear that they might use it to harm themselves. Books and magazines are usually prohibited. Meals arrive without utensils, forcing suicidal people to eat foods like pasta and rice with their hands.

Mental health services in most jails and prisons are so bad that people would rather die than ask for help.

These conditions continue until a mental health professional determines that the individual can be housed safely in a less restrictive environment. This determination can take days to make, as correctional facilities are often so short-staffed that a mental health professional may only be available once or twice a week. In my experience, it is not uncommon for suicidal prisoners to spend a week or more without any meaningful psychiatric assessment or treatment, simply staring at the walls of their bare cells and waiting to be released.

The end result is that many prisoners — particularly those who have served time and know how suicidal people are managed — would rather suffer in silence than subject themselves to the dehumanizing conditions of “suicide watch.” They keep their suicidal thoughts to themselves, and in some cases, they end their lives.

This is the tragedy nobody’s talking about: that mental health services in most jails and prisons are so bad that people would rather die than ask for help.

I imagine many are unmoved by this problem, reasoning that Epstein and people like him deserve no sympathy after committing crimes that victimize others. But Epstein’s case is an exception.

Most people placed on suicide watch in jails suffer from a mix of social and medical problems: withdrawal from drugs and alcohol, serious mental illnesses (like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), alienation from friends and family, poverty and anxiety about their confinement. The U.S. Supreme Court and medical organizations like the American Psychiatric Association have stated unequivocally that prisoners have a right to mental health care that meets the same standard of care available in the community. Yet psychiatric treatment in most correctional facilities remains poor, and suicide remains a leading cause of death in jails. By and large, bad mental health care is still part of the punishment that detainees are expected to endure, even before they have been convicted of a crime.

Mental health treatment in correctional settings involves much more than “suicide watch.”

To seriously tackle the problem of prisoner suicide, we must realize that mental health treatment in correctional settings involves much more than “suicide watch.” I worry that Epstein’s high-profile death will lead correctional facilities to rely more heavily on that harsh and restrictive practice instead of investing the necessary resources to create a system of mental health care that actually helps people. Such a system would involve more therapists, nurses, and doctors, and it would more closely resemble the care of suicidal people in psychiatric hospitals, where they are not routinely locked in their rooms or stripped of creature comforts. Prisoners would be given thorough diagnostic assessments, psychotherapy in group and individual settings, and medication when necessary. Most importantly, they would not be confined in a cell, alone and nearly naked, for days on end.

Jails simply don’t need more suicide-resistant smocks, video cameras and stripped-down cells; they need better access to mental health professionals who can provide compassionate, high-quality care. They need corrections officials who understand that “suicide watch” provides a temporary fix, but that long-term safety is best achieved by keeping prisoners as healthy as possible. There will always be some risk of suicide, but at least we will have moved away from our current system of barbaric, inhumane treatment of people who — no matter what criminal act they have allegedly committed — don’t deserve to die of neglect.