Advertisement

Commentary

The People Protesting Police Brutality And Pandemic Lockdowns Have One Thing In Common

Two starkly different protests have gripped the nation in the past couple of months. The first fought restrictions, including stay-at-home orders, designed to slow the spread of COVID-19. The second fought against police violence and structural racism.

People in the first were frequently armed, faced no police response and received support from the president. People in the second have been generally unarmed, yet met with a violent police response, and received multiple threats from the president.

The first demanded the right to get haircuts. The second demanded the right to breathe. The first was almost exclusively white. The second has been multiracial and led by Black Americans.

Despite these differences, one theme connects these two: a strong distrust of government.

If we want to understand the implications of these protests for public policy and American democracy, we must recognize that the distrust motivating each comes from different histories.

As I show in recent research, the last 50 years have seen government assistance for whites growing more hidden, just as government punishment of Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) has grown more visible. As a result of these changes, Americans of all races and ethnicities trust government at historically low levels. But contained within this widespread distrust, is racial inequality that helped elect Donald Trump.

For BIPOC communities, the last 50 years have involved a tremendous increase in police presence, particularly as officers have prioritized more aggressively pursuing minor crimes. This shift in policing could be seen in Minneapolis when George Floyd lost his life because the police were called to investigate a counterfeit bill. Similar tactics can be linked to the deaths of Walter Scott and Philando Castile (who were pulled over for broken tail lights), as well as Sandra Bland (pulled over for a failure to signal during a lane change).

As former Attorney General Loretta Lynch put it, police have become “the only face of government” within communities of color, and particularly Black communities. In response, BIPOC trust in government has fallen.

At the same time that the government’s policing of BIPOC communities became more obvious and aggressive, its benefits for white people became more concealed.

Most Americans may have gone into the 2016 election distrusting government, but this distrust actually drove racially unequal voting patterns.

A growing number of government policies that primarily assist wealthier, white Americans are now masked as tax breaks and credits. Consider the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction (HMID). This tax break is more generous to people who own expensive homes, a group that is disproportionately white, given America’s racist housing policies. Where the HMID cost the federal government $12 billion in 1967, its cost had ballooned to over $100 billion by 2010 -- 13 times greater than the money spent on public housing that year. Yet 60% of the HMID’s mostly white recipients say they have never been the beneficiary of a government social program.

This increasing invisibility of government benefits for white Americans has left them more distrustful. With whites less aware of how government aids them, it is not surprising that they become incensed when government restricts their movement. Why sacrifice for a country that does nothing for me? Of course, this white anger is ironic given the police’s constant limitation on the movement of BIPOC.

Advertisement

But this irony can also help to explain the election of Donald Trump.

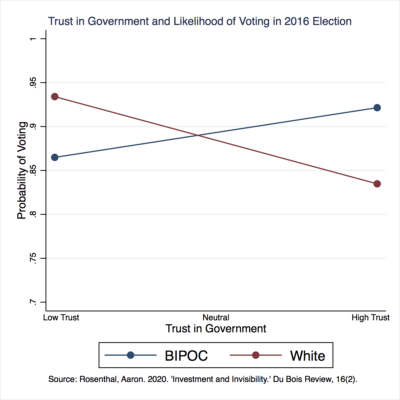

In 2016, distrust drove turnout among white Americans who were convinced government does nothing for them, a trend that President Trump appears to be relying on again in his anti-government response to COVID-19.

In contrast, distrust pushed BIPOC away from the polls. This disengagement makes sense once you recognize how BIPOC distrust of government is connected to the police. If the police are the government, then speaking up to government may not only be ineffective — it could be dangerous.

Most Americans may have gone into the 2016 election distrusting government, but this distrust actually drove racially unequal voting patterns. Considering the important role that declining turnout among BIPOC played in the 2016 election, understanding this dynamic is essential.

Fortunately, there are reasons to believe things are changing. It is not clear that the president can be as successful in running against government while he is at the head of it. In addition, the current activism against police violence shows how police discrimination can be a politically mobilizing force, particularly outside of the voting booth. Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee, might benefit from this mobilization by earnestly atoning for his past failures on criminal justice policy and providing a more progressive vision for restructuring public safety in this country.

Finally, the ongoing protests should remind us that voting is just one way that people share their political voice. Indeed, as the history of the Boston Tea Party demonstrates, there are other methods of calling for change that can be significantly more powerful.