Advertisement

Commentary

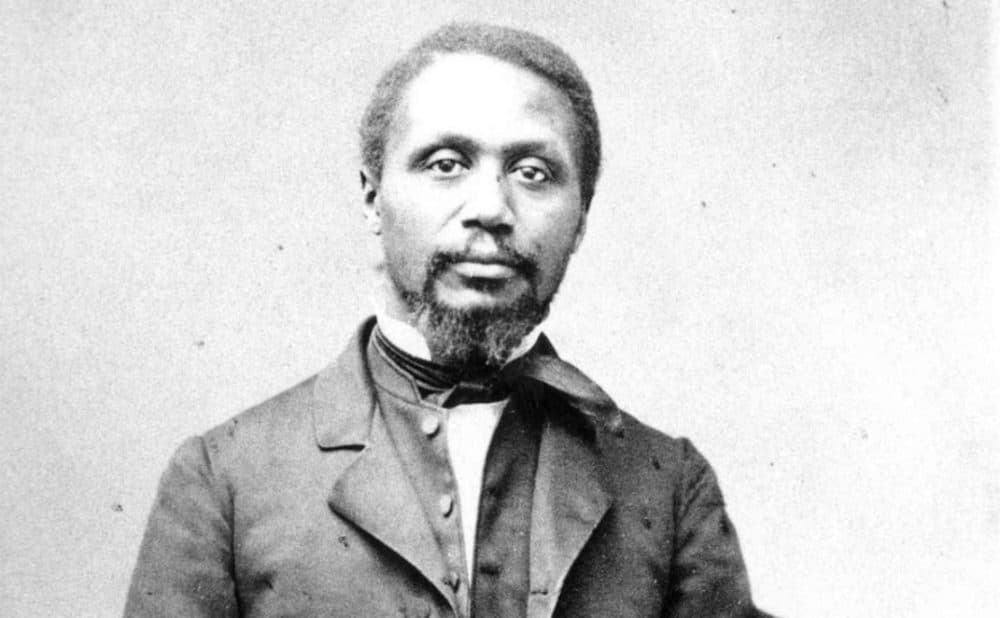

Robert Morris Was A Black Bostonian Who Fought For Freedom. Why Don't We Have A Statue Of Him?

Thousands of protestors nationwide are demanding an end to systemic racism in policing, healthcare and education in the aftermath of the brutal killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others.

One important step, among many, is to remove the monuments to white supremacy that dim our landscape. In June, protestors in Virginia toppled a statue of Jefferson Davis, the president of the failed Confederate States of America, while the Christopher Columbus statue in Boston’s North End was damaged and subsequently removed by the city.

On June 11th, Tory Bullock circulated a petition calling for the removal of the Emancipation Memorial in Park Square. Bullock and other critics object to the way Abraham Lincoln towers over a Black enslaved man, crouched in a degrading position, as well as the statue's misleading depiction of emancipation. If the bronze statue were a story, it would open in medias res with Lincoln, arm outstretched, freeing an enslaved, African American man. The great and gallant emancipator prevails. The long history of African American activism is off-stage, somewhere else, probably forgotten. This statue, a replica erected in 1879, traffics in the hackneyed myth that Lincoln freed the slaves with the stroke of his pen. Members of the Boston Art Commission voted unanimously on June 30 to remove the statue.

We know historically that African Americans were agents of their own freedom. As scholar Kevin M. Levin asks, where are the statues that tell the stories of Black Bostonians?

We know historically that African Americans were agents of their own freedom.

The story of Robert Morris, one of the first African American lawyers in the United States, is worth telling as part of a new commemorative landscape in Boston.

Born on June 28, 1824, Morris was raised in an abolitionist household in the seaport city of Salem, Massachusetts. At 13, he moved to Boston where he worked as a servant in the household of Louisa and Ellis G. Loring, a white abolitionist couple. Ellis Loring, a lawyer, asked Morris to assist in his legal practice. The erudite Morris soon found in law his life’s passion. A legal apprenticeship with Loring prepared him to pass the Massachusetts bar in 1847, making him the second African American lawyer in the state.

In just a few years, Morris had defended African American civil rights in legal cases on Boston school desegregation, slavery and citizenship. Though the nation debated Black citizenship, Morris never did. He thwarted colonization schemes to send African Americans back to Africa, affirming, “This is our country — we are American citizens. Everything about us is American. The sweat of our brows has watered the soil, our labor has cut down trees, cleared the wilderness, built villages, towns and cities. This is our country and our home … [and] we intend to stay.”

Now is the moment to mark Boston’s landscape with statues of great and gallant African Americans ...

Morris worked outside of the courtroom, too, and his abolitionist activities prompted threats of torture, imprisonment and death. In 1850, after the passage of the federal fugitive slave law, Boston became the site of daring slave rescues. In 1851, Shadrach Minkins, a fugitive slave from Virginia, was arrested in Boston and remanded back to slavery. Morris and other abolitionists devised a plan to create chaos in and around the courthouse in order to rescue Minkins, hide him at Elizabeth Riley’s house on Southac Street and ferry him to Canada. It worked. But Morris and eight others were arrested and tried on a federal charge of aiding and abetting. Securing Minkins’s freedom had jeopardized Morris’s own. Morris was later acquitted, but the incident served as a grim reminder of the often-inadequate legal protections for African Americans.

A fundamental belief in truth, right and justice anchored Morris. And these beliefs were shaped by Boston institutions, from voluntary associations to public libraries, as well as Boston literary figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson. Even though the opportunity to attend high school and college had been denied to him and countless other African Americans, Morris championed education, not just book learning but character building. He summed up this conviction in a Civil War-era speech, declaring, “a badly educated man [is one] with the mental culture of a Webster and the heart and devilish propensity of a Jeff Davis.”

Upon Robert Morris’s death on Dec. 12, 1882, members of the Suffolk Bar Association grieved the loss of a smart and successful lawyer who embodied the principles of American democracy.

Now is the moment to mark Boston’s landscape with statues of great and gallant African Americans like Morris and other people of color who shaped the long struggle for Black freedom and racial justice.