Advertisement

Commentary

In The Stories I Tell Myself, My Brother Didn't Die

My brother, whom I adored, took his own life in 2016. He was 54, three years older than me, and lived in New York City. He had been diagnosed with PTSD following an acrimonious divorce, and had been struggling with panic attacks over the previous six months.

During one of many conversations in which I implored him to go to therapy, he asked me, “Why can't you be my therapist?” I had recently enrolled in a master's in social work program, and was attending part-time. I told him I couldn’t be his therapist because I was his sister. Because I wasn't objective. Because I was a student, not a clinician.

Because when we were little, we used to hide behind an old floral couch and eat roasted Spanish peanuts with their red skins on, telling each other they would give us superpowers.

One day over the phone, he asked, “What does a therapist do, anyway?” I told him that talk therapy is about telling your story, and in the story, you are the protagonist, and the plot unfolds around you. I told him that a good therapist helps you look inside the main character — that is you — and you begin to see patterns that develop, and you begin to understand choices you’ve made and how you’ve become the person that you are.

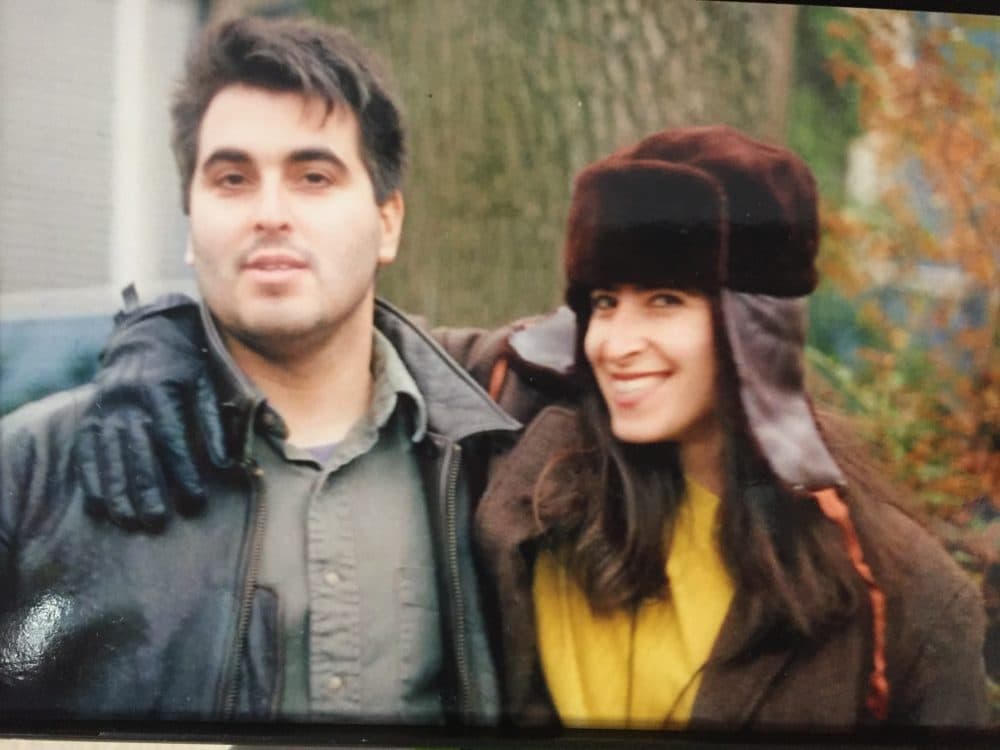

“Do you want me to walk you through what telling your story might be like?” I asked, hoping to cast a line whose hook would reel him in. I described his origins: He was born into a close-knit Jewish family of four children. He was a middle child, a gentle boy among three sisters. His father was a scientist, his mother a teacher. In high school, he devoted himself to long-distance running and eventually, became a star athlete who would go on to set marathon records in several cities. He was a strikingly handsome young man — with angled cheekbones and dark hair — and people were drawn to his wit, his kindness, his killer chess game. I walked him through his college years, girlfriends, graduate school, his career trajectory which ranged from teaching literature in Paris to becoming a small-business owner in New York.

By his late 30s, he was married and had three sons. He loved his boys madly and was the kind of dad who reveled in their friends. His barbecues were notorious, as was his ability to recount and re-enact scenes from "The Sopranos." Then came the blows from which he struggled to recover: His marriage ended in divorce, he lost custody of his children and he had to move out of his home. Soon money was tight. He was hopeless, bereft, financially strapped. He began to sink into despair.

At the end of my 10-minute synopsis of his life, he was in tears. “You’ve described everything,” he said. “Why can't you be my therapist?” Though I loved him, I again said no. I offered to help him find a therapist, and again he declined.

Once I told my brother the story of his life. Now I find myself telling and retelling the story of his death.

We had daily phone conversations that week. He told me not to worry, he wasn’t going to “do anything.” He didn’t have a suicide plan. Each day he seemed to find some goodness, something positive to share with me. He carried home a rocking chair someone was giving away for free. He went to his primary care doctor and got a prescription for anti-depressants. He picked up his youngest son from school on a blue-sky day when the cherry blossom trees were in full bloom. At the end of the week, we had our last phone call.

He took his life moments after he got off the phone with me.

The autumn after my brother’s suicide, I was still in a fog, wrestling with what had transpired between us. I was working full-time and attending the social work program at night. The topics in my classes were merciless: suicide prevention. Depression. Anxiety. Trauma. Sometimes I would walk out of the classroom, lean against the cool brick in the hallway and weep.

One evening, the professor handed out an article related to ethics in social work: in particular, the ethical practice of not treating family members. I read the first few lines. Familial bias interferes with treatment and poses a conflict of interest. I saw my brother’s face and I grew light-headed. Queasy. I really, truly, unequivocally hadn’t wanted to be my brother’s therapist. And yet I’d found myself in that role. The professor told the class that social workers need to be able to live with their decisions in an ethical dilemma. How do I live with mine?

In retrospect, I see that my brother was contemplating suicide, but he didn’t want to burden me, and — more importantly — he didn’t want his plan to be derailed. The morning he died, he got off the phone with me saying he had not slept well the night before and wanted to take a nap. The nap was a lie. Within minutes of hanging up the phone, he slit one wrist, then the other, and then, his throat.

Once I told my brother the story of his life. Now I find myself telling and retelling the story of his death. I have played the events leading up to his suicide, a film reel in my head, too many times to count.

I have played the events leading up to his suicide, a film reel in my head, too many times to count.

I like to imagine alternate paths my brother could have taken to safety. It reminds me of reading the “Choose Your Own Adventure” books to my kids when they were little, the ones that provide variations on endings. Maybe my brother left his apartment that morning, walked to the nearby animal shelter and took home a sad, scrappy dog. Maybe he bumped into a friend who bought him a cup of coffee. Maybe he saw an old movie that reminded him that life is fleeting and precious. Maybe a flyer advertising piano lessons, a text from one of his sons to go skating, the smell of pizza from a wood-fired oven. In this story version of my brother, any of those things could have led to a different outcome.

If I had the opportunity again to tell him the story of his life, I would describe us hiding behind the couch eating peanuts, choosing which superheroes we would become. I would describe him loudly reciting Baudelaire as a teenager at the campsite when I was trying to sleep. I would describe saving enough money from our crappy jobs to travel, hitchhiking in the south of France, in our early 20s. I would describe him chasing our children with nerf guns, all five boys shrieking and running wild in the backyard. I would describe riding my bike alongside him when he went for a run, the hot summer wind pushing against us. I would describe how he overcame a crippling depression in his 50s and how here he is now, walking through the door, arms full of groceries, asking me if I’ve fired up the grill.

Resources: You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline (call or text) at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673). Call2Talk can be accessed by calling Massachusetts 211 or 508-532-2255 (or text c2t to 741741).