Advertisement

Commentary

'A Good Education Saves Lives In More Ways Than One': How Teachers Can Boost COVID Vaccinations

After reading a news article with my high school seniors about the Pfizer vaccine last November, I took a moment to editorialize. “I can’t wait to stick that needle in my arm,” I said, slapping the white board.

“I don’t know,” a girl said from the second row. “I don’t think I’m gonna get it.”

“OK,” I said slowly. “Why not?”

“I don’t want to say,” she said. “I don’t want to sound stupid.”

I squinted one eye. “Don’t you think that’s a bad sign?” I said. “Like, if your reason not to vaccinate would make you sound stupid?”

Friends later teased me about my response, feeling I could’ve been more teacherly.

Maybe so, but the truth is that I’m worn out by so much skepticism. The coronavirus is a hoax. Masks are useless. The vaccine is dangerous. These conspiracies, of course, are the real danger. They’ve led elected officials and everyday people to make decisions that have left more than 400,000 Americans dead.

I’m surprised by how much fear and fake news some of my students have already shared about the COVID-19 vaccine.

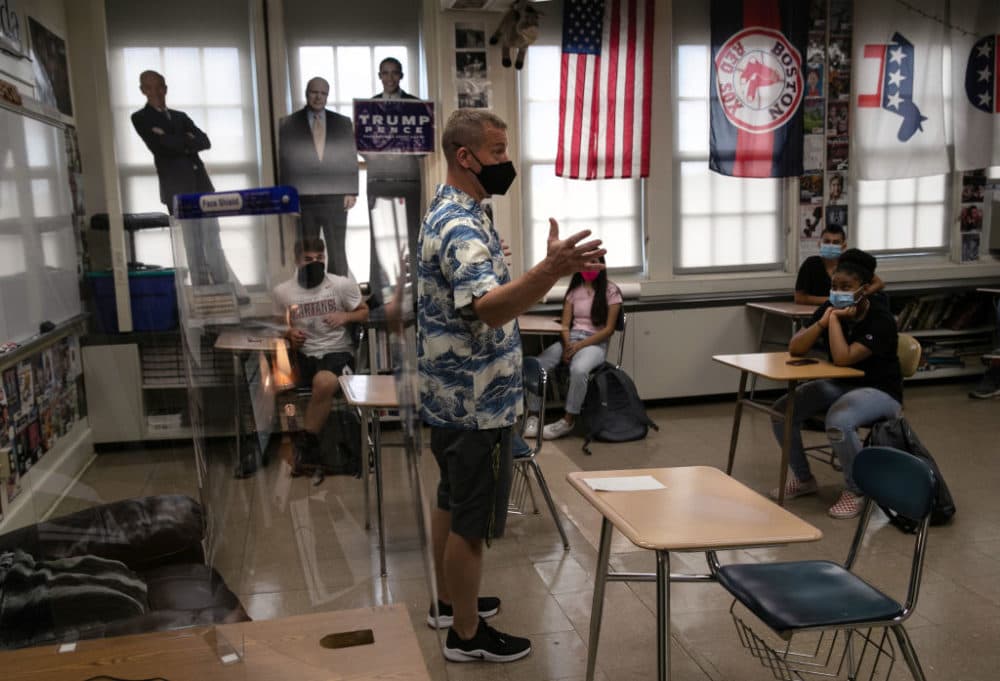

When we were learning in person this fall, my high schoolers were conscientious about washing their hands and wearing their masks. Staying six feet apart was harder for them, but I sympathized. They’re lonely and hormonal. They had gossip to dish and phone screens to share. Still, they tried.

So, I’m surprised by how much fear and fake news some of my students have already shared about the COVID-19 vaccine.

Maybe I shouldn’t be. After all, their skittishness reflects national survey data. It also reflects a national policy of disinvestment from public education — and science education in particular.

The vaccine recently came up again on the Google Meet in my third-period class. “It’s not for me,” one boy said. “Trust.”

When I pressed him on it, he said, “I just don’t wanna put the virus in me. I haven’t gotten it all this time, why would I want it inside me now?” A girl unmuted herself to say he had a point.

Another girl said, “What I don’t like about the vaccine is that it was so rushed.”

When I told my mother, a nurse, she dispelled both myths. “There’s no live virus in the vaccine,” she said, relaying what she’d learned at her university hospital before receiving the first dose. “And they’ve been developing this technology for a decade.”

Public health experts have already begun to disseminate these and other facts.

As the Biden administration gets to work and the COVID-19 vaccination campaign moves forward, I believe K-12 classrooms should be part of a federal strategy to inoculate the public against the many contagious strains of vaccine misinformation. Schoolteachers are trusted, and we regularly see our students. These relationships — no matter how attenuated by remote instruction — should be leveraged.

Health classes are an obvious starting place to review basic CDC fact sheets, but the curriculum could be deeper and interdisciplinary. Imagine if history classes looked at how today’s clinical trials dramatically improve on the horrific medical experiments of the past, particularly those inflicted on Black Americans. Biology teachers could delve into the mechanics of mRNA, spike proteins and herd immunity.

In English classes like mine, we could read excerpts of works like Eula Biss’s “On Immunity,” an essay collection that weeds through vaccine skepticism. We could also review how to evaluate the credibility of scientific sources, preparing students to sift through the specious claims made in group chats and on social media.

Mandatory evidence-based curriculum ... would produce a public less susceptible to fake news in the first place

Short of a federal mandate, teachers and nurses — perhaps through our unions — should collaborate on our own curriculum, responsive to the specific needs and demographics of our classrooms and communities.

We should also think longer term. Properly funded, public schools could serve the interests of public health -- and as more than just checkpoints for childhood immunizations. Mandatory evidence-based curriculum on topics such as vaccines, sexual health and climate change would produce a public less susceptible to fake news in the first place and more likely to get a vaccine, use contraception or support climate justice legislation.

A good education saves lives, in more ways than one.

In the meantime, my students want to do what’s right. Unfortunately, too many of them believe that means not getting the vaccine. One boy who works at a nursing home, for example, told me that a lot of his coworkers chose not to sign up. I asked him why.

“I think it’s mostly ignorance,” he said.

One answer to ignorance is education, so let’s enlist the professionals.