Advertisement

Commentary

I Didn’t Know My Mother, Not Really, Until The Pandemic

When I was 10, soaking up the July sun in the Adirondacks, I calculated how many more summers like that one I could expect to have with my parents. Forty? Fifty, I hoped?

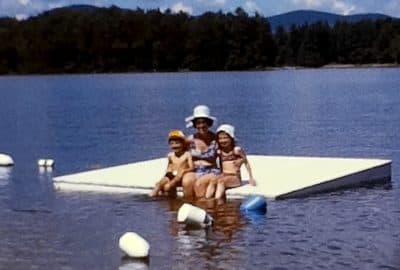

Maybe I'd newly learned the concept of life expectancies, or an elderly relative had died. We'd been in the U.S. five years then. We were at Schroon Lake: silky water, rolling green hills, shimmer of sky. We had a cabin with knotty wood-paneled walls; a pebbly beach. The worry creases softened on my parents’ foreheads when we were there. We swam and fished and read and flew on swings. We ate candy bars mid-day. But what we did hardly mattered. It felt like heaven, being in that place with those people: mother, father, brother. I didn't want it to end.

In mid-life, in the midst of a global pandemic, I spent much of the summer with my mother, who six months earlier had lost her husband of 58 years. She and I had each isolated for months, as instructed, in our separate homes in different states. It wore on us. As soon as quarantine requirements between New York and Massachusetts were lifted, I drove to pick her up her so we could isolate together. I persuaded her to move to Boston for the year.

As an adult, I know that not all 10-year-olds make the kind of calculation I made. Not all 10-year-olds live with the anticipation of loss. But as a child immigrant from Romania, I'd watched my grandmother pine for the company of her daughter, whom we'd left behind. I'd felt our family's fabric tear. At the time I didn't have the words to make sense of it, nor did we really discuss it.

At 10, I also didn't realize that in a few short years, I'd want to spend my summers in an entirely different way. That joy would later come from summers with my husband and our own children; with our friends. I didn't understand that change inevitably shuffles the constellation of loved ones around us. I struggle to accept that even now.

My mother moving to Boston was a practical decision: she’d be closer to family during a crisis. And friends commended me for being a good daughter.

But the sense of an obligation fulfilled doesn't account for the surprising sheer pleasure of her presence, as we navigate a changed world and the ways we each are still ourselves, and also different.

My mother is developing aspects of her personality that were sometimes eclipsed in her roles as wife, mother, grandmother. "I've always wanted to live near a river," she tells me now, walking along the Charles River Esplanade. "I've always wanted to swing in a hammock."

Advertisement

I don't calculate how many more summers I'll have with my mother, but rather, make room for the impromptu picnic when it's 70 degrees out in November.

She's borrowing literary fiction from my shelves. Using new technologies to reconnect with childhood friends, some of whom now live in Massachusetts. Telling me stories about her youth that she never divulged before.

I didn't anticipate my delight at her delight as she discovers the bronze ducks in the Public Garden, with their ever-changing outfits. My renewal of hope as she rebuilds stamina with daily walks around the pond, where we sometimes meet for lunch. My pleasure watching her bargain at the Copley farmers' market — even through a mask.

For the first time in decades, we have spur-of-the moment casual dinners together. I let her cook for me. My concern that this was a burden quickly morphed into understanding how critical it is to feel competent — to still be able to care for those you love.

Of course, we also argue, but we're both more aware of the triggers. We sometimes even talk about the triggers.

What I reveled in and couldn't name that summer as a 10-year-old was the delight that comes from immersion in a moment in the company of people who matter to you. Some of that joy was embedded in particular people: mother, father, brother. But the capacity for that delight transcends those specific people, and that moment, and can exist even in this most difficult year.

After a walk along the gravel paths at World's End in Hingham, followed by a lobster boil, my mother says, "it's been such a lovely day." And: "you don't have to worry about entertaining me. I love to see you, but you have your own life to live."

The pleasure of being together, and the freedom to be apart: like the summer I was 10. This summer, like that one, I feared summer's end.

But summer is long gone and we're coping. My family has reconfigured again and again since I was a child. I miss people I loved and lost. I don't calculate how many more summers I'll have with my mother, but rather, make room for the impromptu picnic when it's 70 degrees out in November. And I count myself lucky, because even during this pandemic, new people have appeared in my life whose presence sparks hope and gives pleasure.

I haven't mastered the ability to acknowledge what's lost and what's gained when my expectation of who constitutes my closest circle changes. But I work at it every day.