Advertisement

Commentary

I Write Obituaries For The New York Times. Memorializing People In A Pandemic Feels Like A Different Assignment

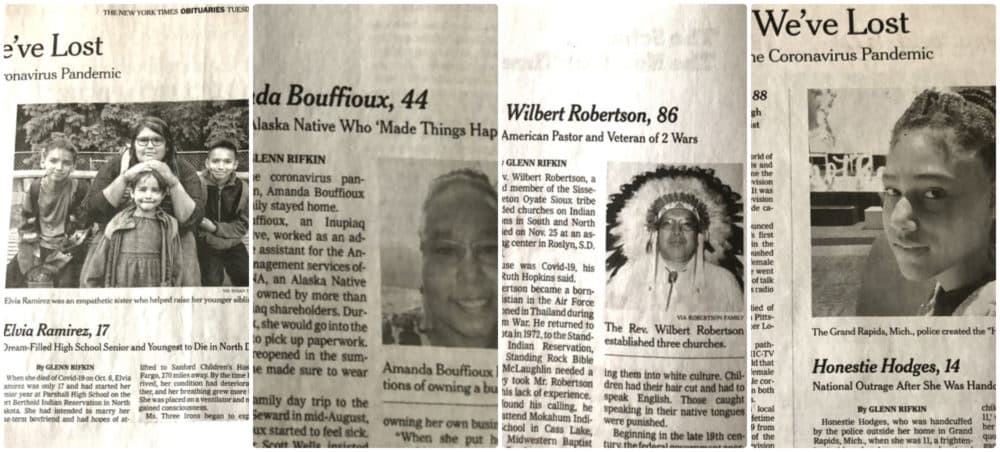

When I wrote an obituary for Elvia Ramirez for the New York Times last October, it put the coronavirus pandemic into a starkly different light.

Elvia, a Native American from Parshall, North Dakota, was just 17 years old, an empathetic and loving daughter and sister, who had just started her senior year of high school. She was, at the time, the youngest person to die in that state from COVID-19, and when I spoke to her mother, Susan Three Irons, about Elvia’s last days, she sobbed as she tried to grasp this devastating loss. She could not be with her daughter when she died. A nurse arranged a video call, without audio, so she could at least see her daughter. She didn’t know that her daughter had gone into cardiac arrest at that very moment. The nurse turned the camera toward the floor so she wouldn’t have to see what was happening. After Elvia died, the doctor held a phone to Elvia’s ear so her mother could utter a last goodbye.

Being an obituary writer means confronting death while celebrating a life, and you have to develop an ability to create some distance in order to fulfill your assignment. But this one, and many others I’ve written for COVID victims, felt very different. I had to fight back tears as I wrote this heartbreaking obituary.

More than anything, these assignments cut through the burgeoning numbers and bring each death, each individual passing, into stark reality.

What we’re seeing is the anonymity of big numbers. The death toll in the U.S. due to COVID-19 has soared past 400,000 and will inevitably pass a half million in a matter of days or weeks. After nearly a year of trying to cope with the nightmare of this pandemic, the number of cases and deaths is so large that it is simultaneously shocking and numbing. We are told this is more than all those who died in World War II and all subsequent wars. We know a vaccine is now available but the dying continues at a staggering rate.

I had never envisioned myself as an obituary writer, but career paths can take odd twists and turns if you are at it long enough. For much of the past several years, I have been writing obituaries for the New York Times, and though I’ve spent most of my four-decade long career as a business journalist and author, my identity is now inextricably tied to the obits page. And writing obituaries in the time of COVID has taken on a whole new meaning.

When my editor at the Times asked me last year to contribute to a new feature on the obituary page called Those We’ve Lost to the coronavirus, I found myself confronted with a very different kind of assignment. Unlike the usual obituaries I have written about notable people, luminaries in their field, famous or accomplished folks who are deemed worthy of a New York Times obit, these are about ordinary people, young and old, who mattered deeply to their family and friends and colleagues and whose common connection is that they were lost to a scourge rampaging around the nation and the world.

Advertisement

There was Honestie Hodges, a 14-year-old Black girl who died in Grand Rapids, Michigan, just days before Thanksgiving. Her broken-hearted grandmother called her “my beautiful, sassy, smart, loving granddaughter.” She had no health issues before getting COVID. Richard Means was a 78-year-old Chicago attorney who devoted his career to fair elections. He died in December. He hosted an “anti-tyranny” Zoom gathering just before the presidential election. Reverend Wilbert Robertson, an elder of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux tribe, died in November in South Dakota. He had survived a childhood spent in the infamous “boarding schools” where Native American children were taken, away from their homes and parents, to learn to assimilate into white culture. “My life is filled with memories of him sacrificing for others,” his daughter told me.

They were all swept away in quick and devastating fashion, usually alone in a hospital room where a mother, a husband, a child, a friend, could not be by their side to ease the fear and say goodbye before they passed.

I want what I write to be a marker that illuminates, not just an ending, but a beginning -- and a journey that mattered.

More than anything, these assignments cut through the burgeoning numbers and bring each death, each individual passing, into stark reality. These are not just statistics, these are people with names and faces and a seat at the dinner table. There is, in each instance, the belief that their time should not have been up. There was more, often much more, to live for.

My job is to honor a life, offer the last word for a person who succumbed to this insidious virus, and share their accomplishments, their hopes, their dreams and their legacy. Having an obituary in the Times is a small bit of immortal recognition. Many of the relatives I’ve spoken with are pleased, through their grief, to have the story told in a major newspaper,

When we remember the 1918 flu pandemic, it is the individual stories of those who died that shed light on the enormity of the disaster. In 100 years, these small COVID narratives will be historical documents testifying to the magnitude of this tragedy. To that end, I want what I write to be a marker that illuminates, not just an ending, but a beginning — and a journey that mattered.