Advertisement

Commentary

Why I'd Rather Live Woody Guthrie's Words Than Sing Them

When Jennifer Lopez sang "This Land is Your Land" at the presidential inauguration in January, my phone blew up with messages saying, “J. Lo’s singing your song!”

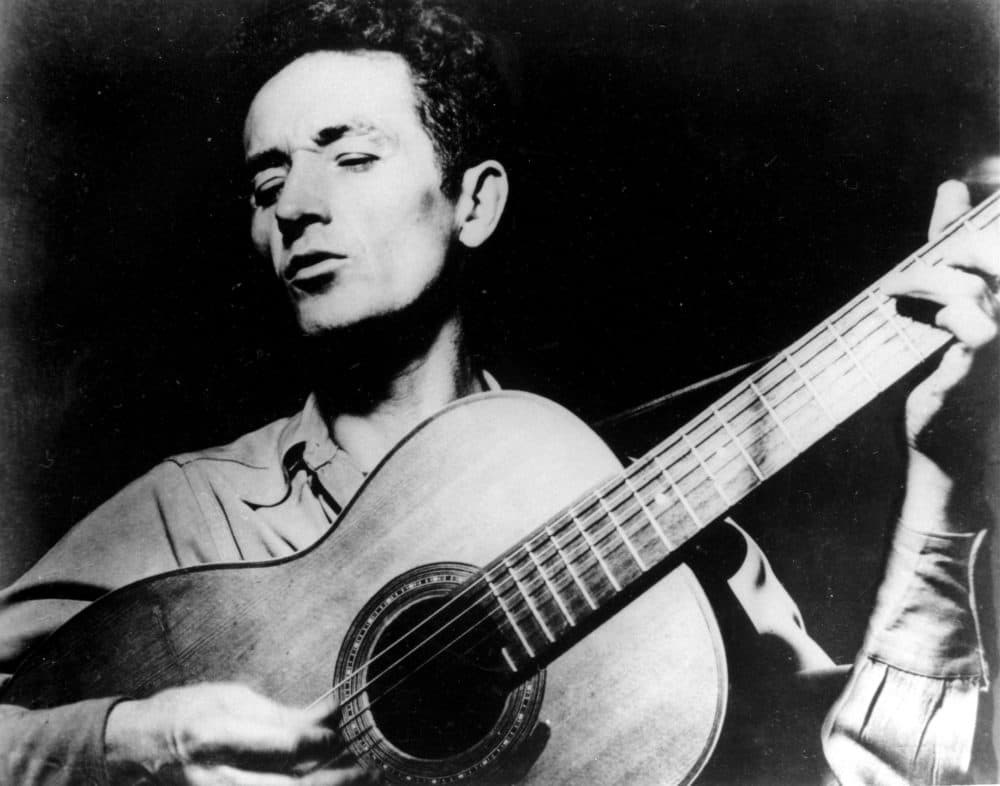

It’s understandable why so many friends and peers associate the song with me: I talk about Woody Guthrie an awful lot. Ever since I first read “Bound for Glory” in high school, I’ve never quite been able to shut up about the man: this Walt Whitman with a James Dean sneer, this Will Rogers with a razor in his shoe, this proto-punk poet who was just anarchic enough to believe in human decency, American potential, and — though he sprouted from deeply racist roots in Jim Crow Oklahoma — a racially inclusive society.

And so, as you’d expect, his anthemic, tongue-in-cheek retort to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” has a special place in my heart, too. It’s long been a central pillar of both my public performances and my educational programs for kids.

In the school programs I teach on social justice, I use the song to unpack the idea of ownership. Whereas the chorus and first two verses speak to what we collectively get from America, the rarely sung additional verses ask what we owe — to each other, specifically.

In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple;

By the relief office, I'd seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

In the programs I teach on writing, meanwhile, I use the song to teach about structure and rhyme scheme, and the ways in which a masterful lyricist like Guthrie is able to break all the rules.

But lately, I’ve been rethinking my reliance on the song in my teaching, and the unintended message I may be sending to kids through its lens on American history — a lens that obscures the fact that “our” land was, in fact, taken from its native inhabitants by force.

In 2019, Mali Obomsawin, a member of the folk trio Lula Wiles, wrote a piece for Folklife Magazine on how the song speaks to her as a citizen of the Abenaki First Nation: “‘This land is your land, this land is my land’ … These lyrics shake me up like a soda can every time I hear them.” She makes a compelling case for why the lyrics, intentionally or not, reinforce Native oppression.

The article was met with quick backlash. Conservative papers reacted about how you’d expect, but the reaction from many on the left was damning too. What both sides shared was a breezy dismissal of the concerns of a woman of color — one with multi-layered expertise on the subject — by largely white male authors.

Obomsawin is not the first Indigenous American musician to object to how “This Land is Your Land” has been sung and used over the years. Raye Zaragoza has spoken out about it too, and Buffy Sainte-Marie, one of the best-known Indigenous performers of all time, has long voiced her objections.

Somehow, though, I’d never heard these perspectives until recently. Maybe it’s because the media is publishing wider perspectives than they used to. More likely it’s because I’m paying more attention.

I don’t want to throw away my beloved “This Land is Your Land.” But the opinions of musicians like Obomsawin and Sainte-Marie matter to me.

Like many white Americans, I was jolted out of a complicit slumber by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor this past year. Instead of just shaking my head and dashing off another ineffectual social media post, I decided to go deeper this time. I helped start a racial justice coalition in the Boston suburb where I live and another in children's music. I worked more closely than I ever had with Black and brown peers in these groups. I heard their stories, I asked questions. I learned to talk a little less and listen a little more.

And then, a few months ago, I was faced with a dilemma: I received a Grammy nomination, along with four other white nominees, for Best Children’s Album of the Year. Unlike when I was nominated as part of an all-white slate in 2013, this time I recognized that there was a problem.

Artists of color have been deeply underrepresented in this category over the years. While there are complicated and nuanced reasons for this, the end result is a lack of representation that is not OK — especially in a genre like children’s music, where musicians are uniquely tasked with modeling fairness, kindness and inclusion.

So, after much deliberation and communication with others involved, I and two of the other five nominated acts decided to respectfully decline our nominations. An NPR story on our decision led to a rash of national coverage. Like Obomsawin, we were trolled by white nationalists, but we also heard from many on the left who felt our move was “misguided.” Not surprisingly, the vast majority of those who weighed in were white.

I don’t want to throw away my beloved “This Land is Your Land.” It’s one of the songs that made me want to be a songwriter and that, despite its shortcomings, still resonates with me deeply. But the opinions of musicians like Obomsawin and Sainte-Marie matter to me. If I value their worth and intellect as musical peers and human beings, then I need to make a genuine effort to hear them — to check my defensive instincts and be willing to reconsider my assumptions, even around something I love.

This is the work of allyship. It’s not about “political correctness.” It’s not even about getting it “right.” It’s about trying to create more space for other voices and being willing to loosen our grip on the things we’ve convinced ourselves we need.

In this case, it may mean coming around to the idea that the best way to honor Woody Guthrie’s vision of an equitable and inclusive nation is to live his famous words rather than sing them.