Advertisement

Commentary

My Dad Was A Political Extremist. The 'Big Lie' He Believed Hurt Us All

Each time I watch footage of the rioters who attacked the capital on January 6 — or of the 440 arrested since then — I do not see the armed, enraged and emboldened insurrectionists as much as I envision their children, spouses, parents and siblings, all of whom will live with the consequences of their choices as surely as the actors themselves.

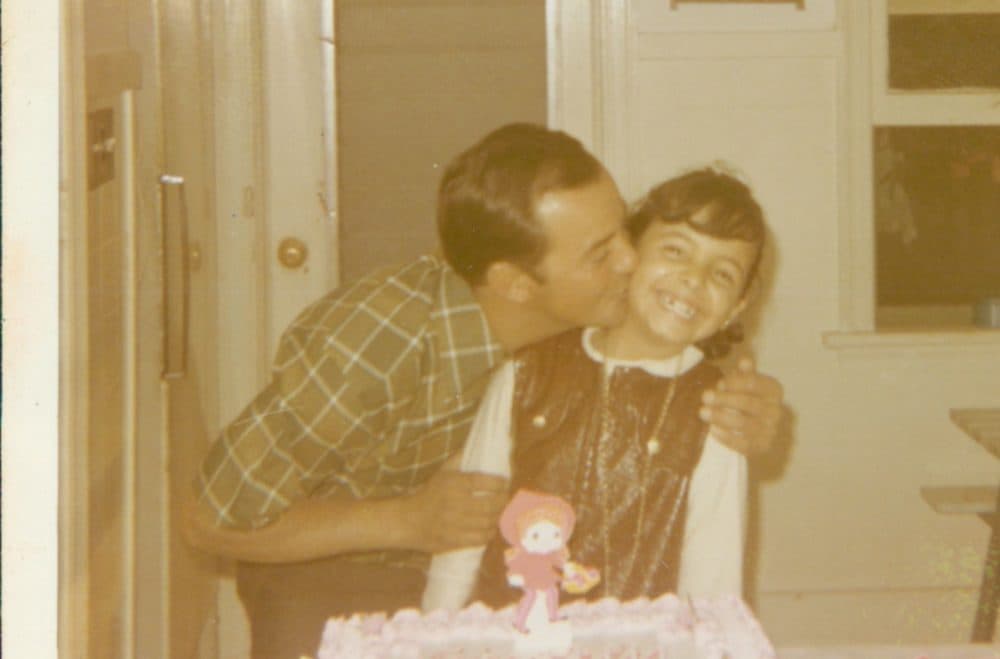

As the daughter of an extremist, I should know. At 58, my life continues to be shaped by my father's actions, taken decades ago in the name of patriotism and freedom, and by the direction of powerful and seemingly unbeatable ideologues.

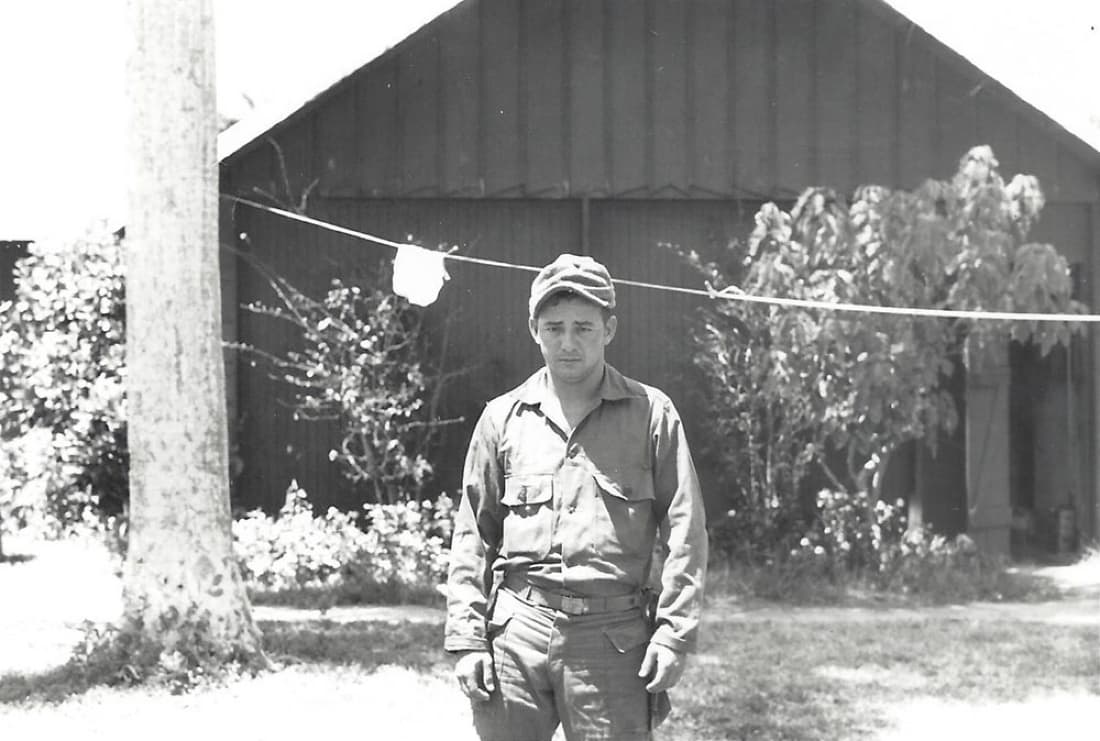

When my parents fled Castro's Cuba in 1959, for Miami, they believed their exile was temporary. In the summer of that year, the CIA began recruiting thousands of Cuban exiles, my father among them, to overthrow Fidel Castro's communist regime. These young revolutionaries were from all walks of life, grasping at a chance to do something heroic and noble. For my father, that promise was intoxicating and unshakeable.

Early on the morning of April 17, 1961, thousands of Cuban exiles, financed and directed by the U.S. government, landed at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba. The three-day invasion did not go well. At the last minute, the Kennedy administration refused to supply the proper air support or U.S. troops as promised.

After the short war ended, and the Cuban exiles went home to their families, my father remained an unwavering soldier, isolated in his battle to destroy Castro long after the Americans forgot what they had started. I was born after the failed invasion and grew up in the hazy illusion that my father was exceptionally virtuous for refusing to give up his ideologies, even at the expense of his wife and children.

For many years, the U.S. government kept him in their inner circle, stoking his rage and need for vindication. But then, when the political winds shifted, and they no longer needed him, they threw him to the curb. Once discarded, my father joined several extremist Nationalist groups with the mission to assassinate Castro, and according to my father, defeat the Red Tyranny.

What began in 1959, as a righteous call to action to eliminate the threat of communism in the Western Hemisphere, launched in my father a life-long obsession to free Cuba at all costs.

Advertisement

When did my father cross the line from being a patriot to being a mercenary?

Growing up in his orbit had its upsides. He was charismatic, competitive, charming, athletic and generous to strangers. But he could also be violent, absent for long periods, inconsistent as a provider and deeply paranoid. I learned early to keep secrets, trust no one and believe that people were either good or bad based on political ideology alone.

As a psychologist, now, I am reminded often of Maslow's hierarchy of needs and a human's desire for safety and food, as well as a need for belonging and self-actualization. Maybe my father had needs that were met when he became part of what he felt was a critical mission to free his homeland, and found his identity as a freedom fighter.

But what, then, after the Bay of Pigs? What, then, after the Capitol riot?

When did my father cross the line from being a patriot to being a mercenary? I know from the literature, and my work with clients, that one's vulnerability to having extremist beliefs or being radicalized lies in the belief that: 1) an injustice has occurred, 2) you are part of something greater than yourself, and 3) you are necessary.

It was hard for me to estrange myself from my father, but when I became a parent at age 36, the fear of his increasingly radical beliefs made it necessary. His ideas were absolute — free Cuba or die.

Whether we choose to see it or not, some of those men and women climbing over barricades and storming the halls of the Capitol with rage have children now sentenced to live in fear.

Extremist ideologies can, to those who believe in them, justify certain destructive behaviors, be it bombing a sugar refinery in Cuba or vandalizing the U.S. Capitol. Of course, some extremists are not violent. But violent or not, many extremists are methodically groomed to do the bidding of self-centered leaders who care nothing about those pledging blind allegiance — never mind their families. We are just collateral damage in their cult of personality and politics.

I was struck last week when I felt myself cheering on Congresswoman Liz Cheney as she was dethroned from Republican leadership in the U.S. House for refusing to endorse the former president’s "Big Lie." Cheney and I are ideological opposites, but the child inside me felt protected by this no-nonsense woman standing up to bullies and speaking out against tyranny rather than perpetuate the lie. Her resistance cast doubt on a toxic narrative that few GOP leaders dare to question. To civilian insurrectionists, her bold resistance also signaled that there is still time to abandon blind allegiance before it is too late.

Whether we choose to see it or not, some of those men and women climbing over barricades and storming the halls of the Capitol with rage have children now sentenced to live in fear of those moments that their parent’s fury, discontent and unrealized victory comes home to roost. Whether the event happened 60 years or several months ago, we would do well to think about the invisible casualties left in the wake of extremism of any sort.

It's not too late to turn some supportive attention to the families among us that live through historic flashpoints, so that their battle scars are situational and not generational.