Advertisement

Commentary

I Am A Black Woman In Academia. Nikole Hannah-Jones’s Tenure Saga Isn't Unique

When a Pulitzer Prize, a MacArthur “genius” award and transformative scholarship are not enough to obtain job security, all academics should be concerned.

I, like many people, have closely followed the University of North Carolina tenure saga of Nikole Hannah-Jones. During the controversy, it became clear that political factions connected to UNC were not merely trying to diminish Hannah-Jones’s accomplishments, they were also attempting to block her from the protection that tenure provides.

For Black academics like myself, these high-profile denials are not just canaries in the coal mine, they reflect a continued legacy of cautionary tales that haunt Black scholars. The typically unspoken practice of blocking those whose work often directly speaks to the violence of white supremacy or the promotion of Black humanity is old and ongoing.

While right-wing pundits decry academia as a haven for liberals, in truth, it is far from the progressive utopia they so fear. For years, statistics have circulated regarding the low numbers of Black faculty at institutions of higher learning. The problems of recruitment, retention and representation impact Black women scholars most acutely.

Most American colleges and universities have only a handful of tenured Black female scholars — if any. Dr. Elan Hope tweeted about these dreadful numbers among Black women faculty who have earned full professorships (the highest rank a professor can earn). In 2019, at North Carolina State University, there were 643 tenured full professors and nine were Black women. At Duke University, there were 1,007 tenured full professors and eight were Black women. At the University of New Mexico, there were 296 tenured full professors and two were Black women. At Penn State, there were 1,190 tenured full professors and five were Black women. The list is endless.

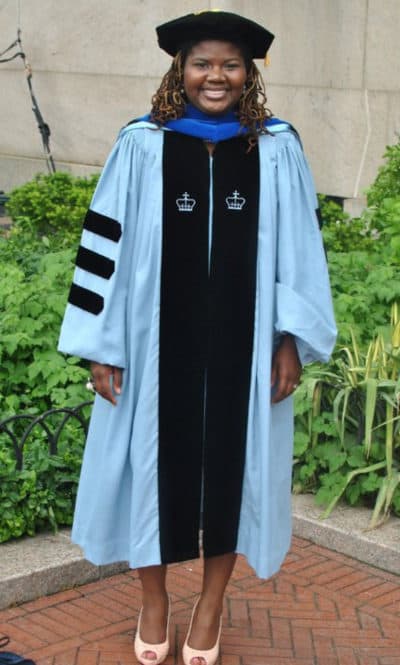

I have experienced the challenges of entering the professoriate firsthand. Despite how often I was told, “You’re from the Ivies, you’ll get a job,” it took four years to obtain a tenure-track position after I earned my Ph.D. During that time, I was teaching four classes in the fall and four classes in the spring at a university best known for its basketball program. The job left me with little to no time to publish, and my working conditions were subpar. I am an Americanist, but there I spent all my work prepping for courses that were largely outside my expertise, such as World Civilization and Western Civilization. Teaching these courses drastically impacted my student evaluations, which ranged from questions regarding my intelligence to statements about my wardrobe. The university offered me $32,000 when the average starting salary at the time was $50,000. I was told I would have my own office but found out later I would be sharing with two other adjuncts. I pushed back where I could, but it was difficult. Out of over 500 faculty members, I was the only African American woman teaching at the college.

Advertisement

So I am thrilled to know that Nikole Hannah-Jones and Ta-Nehisi Coates will be teaching at my alma mater, Howard University. From their beginnings, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have been safe havens from oppression. As a print journalism major in the school of communications, I know firsthand what was it was like to be taught by giants and treated with respect. I went to Howard to learn uninhibited by racism. For the first time, I felt free. Howard also equipped me to face a world that would be openly hostile and passive-aggressive in undermining my talent and skills. And although I am equipped, the fight is exhausting.

In a statement to UNC-Chapel Hill, Hannah-Jones wrote that she was honored and grateful “to join the long legacy of Black Americans who have defined success by working to build up their own.” She added, “For too long, powerful people have expected the people they have mistreated and marginalized to sacrifice themselves to make things whole. The burden of working for racial justice is laid on the very people bearing the brunt of the injustice, and not the powerful people who maintain it. I say to you: I refuse.”

I am empowered by both her refusal and her choice to teach the next generation of Black journalists.

Hannah-Jones’s choice is not a game or a PR stunt. It’s freedom.

As a woman, teaching has done this for me as well. I get to help equip my students, as my professors equipped me. Together, we work to upend the patriarchy. And white supremacy. We get to refuse limitations on our ability to learn and lead.

Fellow Howard alum, Toni Morrison, said it best: “I tell my students, 'When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else. This is not just a grab-bag candy game.”

Morrison is right. Hannah-Jones’s choice is not a game or a PR stunt. It’s freedom.