Advertisement

Commentary

Stephen Sondheim's art wasn't easy. It wasn't meant to be

Once, yes, once for a lark.

Twice, though, loses the spark.

As I said to the Abbot,

“I’ll get in the habit

But not in the habit.”

You’ve my highest regard,

And I know that it’s hard–

Still, no matter the vice,

I never do anything twice.

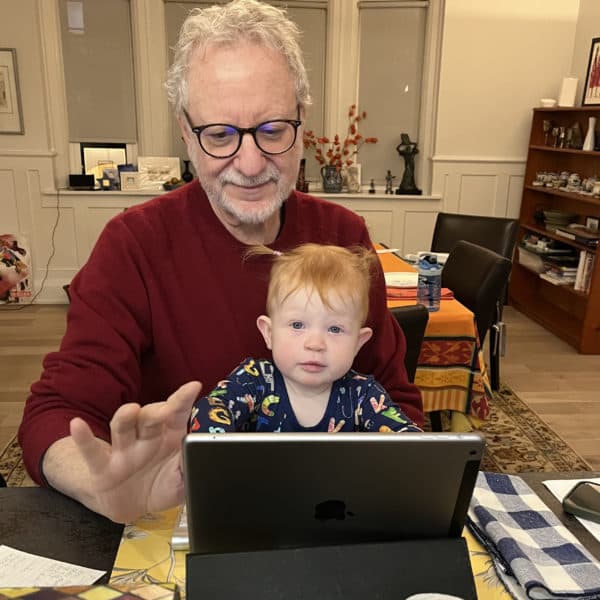

Call me heretic, but I couldn’t resist starting this valedictory to Stephen Joshua Sondheim, who died on November 26 at 91, with a lyric not from one of his legendary musicals, but from a song he wrote for the film “The Seven-Per-Cent Solution.” There are, in the Sondheim canon, plenty of sharper lyrics, lyrics that cut more acutely, draw blood more swiftly or, conversely, send the listener into paroxysms of amazement — The child is so sweet, and the girls are so rapturous / Isn’t it lovely how artists can capture us? -- to choose from. Yet one essential clue to the genius, to the man who blew up Broadway and put it back together in his own image, is that Sondheim never did anything twice. Within that truism is the ambivalence (to use one of his favorite words) -- of fearlessness urged along by fear — that drove him to greatness.

You may keep, for example, your sentimental Sigmund Rombergian paeans to love, your Ira Gershwin predilection for mush; in Sondheimia, love always is a double-edged sword.

[In] Sondheimia, love always is a double-edged sword.

A drama critic, reporter and editor, I've engaged with every Sondheim show since "Company" upended Broadway norms in 1970, and with the man himself on many occasions as well. As far back as “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” the 1962 musical that earned him his first Broadway credit as both composer and lyricist, he wrote, If you start to feel a tingle / And you like remaining single/ Stay home, don’t take a breath / You could catch your death / ‘Cause love is around. That song was eventually cut from “Forum,” but the tongue-in-cheek equation of love with death would wind its shape-shifting way through all of Sondheim’s work, from “The Little Things We Do Together,” “Company’s” ode to marital discord, to “Send in the Clowns,” from “A Little Night Music” to “Passion,” in which the sickly, obsessed Fosca sings, of her love for a handsome soldier who is otherwise engaged, A love as pure as breath / As permanent as death / Implacable as stone.

Cheery, right?

None of these shows is anything like the other. But if Sondheim never repeated himself, certain themes, like certain musical motifs, suffuse his words and his music. He merely (!) expanded the available palette from the primary colors typical of operetta and matinee musicals to a thousand refulgent pixels, much as Georges Seurat, the hero of his 1984 masterpiece, “Sunday in the Park With George,” had done with dots in the after-shadow of Impressionism.

Sondheim found — no, he created — new, ferociously challenging ways to write about love, friendship, youth, following your bliss, following your hiss, dreams dreamt, and dreams wrecked on the unforgiving shoreline of reality.

Most important of all, Sondheim wrote for grown-ups. His characters were complex, and so were the songs they sang to express themselves.

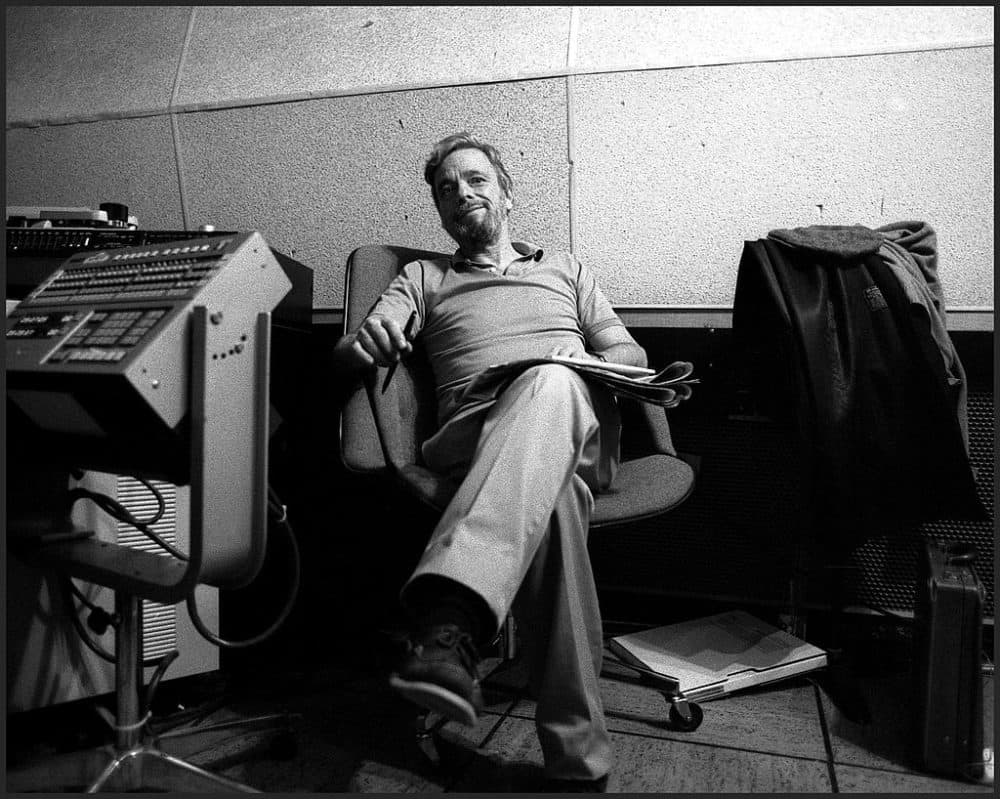

There’s poignance in his trust that audiences would get him, even if that trust proved, more often than not, to have been, well, theoretical. In the decade from 1970 through 1981, when his most influential collaborator was director Hal Prince, Sondheim produced an astonishing catalogue of shows that fell under the rubric of “concept musical”: “Company.” “Follies.” “A Little Night Music.” “Pacific Overtures.” “Sweeney Todd.” “Merrily We Roll Along.” They left some critics stroking their chins (when not being overtly hostile) and ticket-buyers all but waving their fists at his cerebral lyrics and the post-modern melodies that fell on ears unattuned to anything but Pop palaver.

His characters were stick figures, mouthpieces, people grumped. “Audiences like shows about people,” as Variety’s dismissive review of “Sunday in the Park” snarked. “They’re funny that way.”

Others, critics and at least some folks who paid for their tickets, would champion Sondheim’s boldness in choice of subject (a mass-murdering barber and his psychotic helpmeet, say, or forced free trade in the Pacific), paired with a musical vocabulary that challenged, rather than coddled, the ear.

In truth, Sondheim had received his tutelage under rule-busting giants before him, notably from lyricist and librettist Oscar Hammerstein II, and composers Leonard Bernstein and the serialist Milton Babbitt, who taught him, he wrote, that “the best art, or at least the kind that I like best, usually involves making the most out of the least.”

Determined to be a words-and-music man, Sondheim reluctantly agreed to make his Broadway debut as lyricist only, in collaboration with Bernstein, librettist Arthur Laurents and director Jerome Robbins; the result was “West Side Story” in 1957. That was quickly followed by another transformative collaboration, this time with composer Jule Styne (and Laurents, again), on 1959’s “Gypsy.”

Comprising one of Sondheim's most accessible and knowing scores, “Merrily We Roll Along” in 1981 was the Broadway flop that closed one rich chapter of Sondheim’s career and opened another: His split from director Hal Prince would take decades to heal, but the rift led to the composer and lyricist's connection with James Lapine, a Carl Jung-influenced playwright, director and visual artist. Sondheim's work with Lapine went even further out on a limb than the shows with Prince, beginning with their masterpiece, “Sunday in the Park With George,” and continuing with “Into the Woods,” and the chamber opera “Passion,” the latter a work so intense that it left audiences squirming, some over the intensity of its high dive into the dark pool of obsessive love, others in abashment at the (literally) naked melodrama unfolding at the Plymouth Theatre (now the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre).

For Sondheim, the musical theater is a living thing, an organism undergoing constant change while serving to teach, to challenge, and, above all, to delight.

Those works, as if in reproof to the naysayers who found Sondheim chilly (as they had with Bernard Shaw before him and Tom Stoppard in his own time), those shimmering works sparkled with genius. But their legacy also includes some of the most gorgeous and emotionally resonant songs ever heard on a Broadway stage. A quote from my “Passion” review hung over the entrance to the Plymouth, and here’s a secret: I was wildly proud of that.

If Sondheim himself never did anything twice, his legion of admirers was ever happy to do so. Revivals and revisals of his work -- on Broadway and off, in concert halls and opera houses and store-front spaces around the world -- have become mainstays of the repertory. New York is currently hosting two, a timely off-Broadway return to “Assassins” and a Broadway revival of “Company,” both of which Sondheim enthusiastically approved.

For Sondheim, the musical theater is a living thing, an organism undergoing constant change while serving to teach, to challenge, and, above all, to delight. As the song goes, now we know.