Advertisement

Commentary

It's been a long, arduous week for Mass. teachers. Why won't our state leaders apologize?

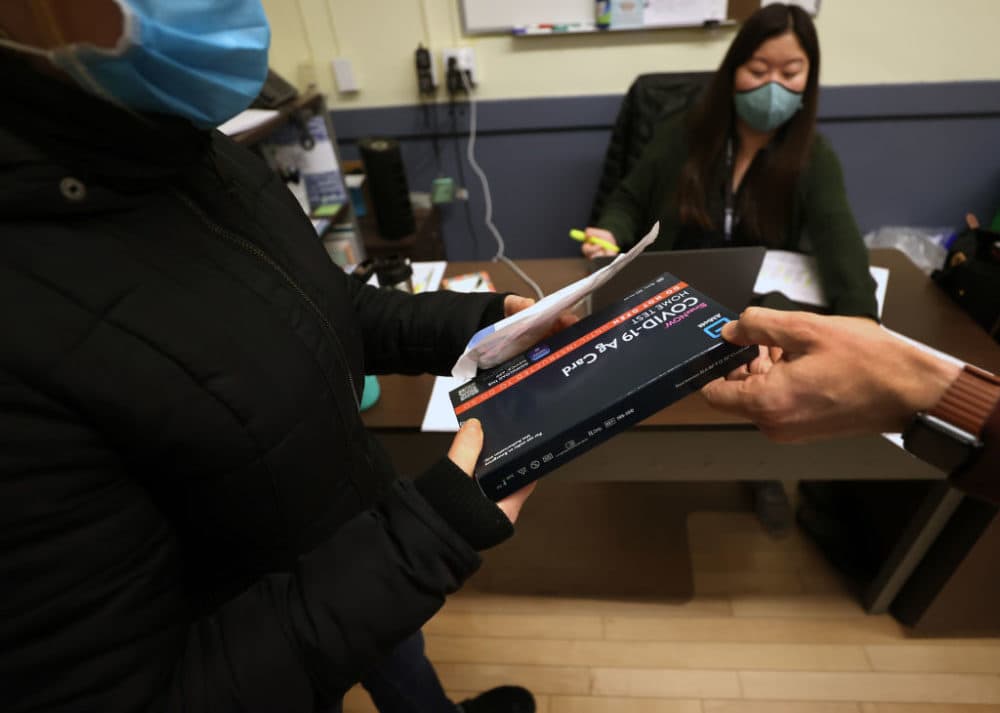

This week, teachers across Massachusetts received rapid COVID tests and masks courtesy of the state. This gesture, while important, was marred by the fact that some districts received expired tests, and that an unquantified, but seemingly large, number of teachers were given masks that are not sufficiently protective against the virus.

These mistakes are not surprising. Instead of taking a more proactive approach to managing COVID in our schools by ensuring access to masks and testing prior to breaking for the holidays, the state waited until the very last minute to offer these resources to districts, forcing district officials to drive to distribution locations on Sunday of their winter break, and then to frantically create plans for distribution. There was no time, given the rapid turnaround, for the state to check its work.

And when evidence of these expired tests and less-protective masks began to come to light, I was frustrated, but not surprised, that Gov. Charlie Baker and the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) doubled down on their choices, claiming that the masks were vetted by MIT, and that if districts handed out expired tests, it was their fault, and not the fault of the state. Blaming teachers and schools seems to be the modus operandi for our state leadership, and we have, unfortunately, become accustomed to that.

There was no time, given the rapid turnaround, for the state to check its work.

So, I’m not sure why I feel so surprised, or unsettled, by the subsequent unwillingness of the state to take responsibility or apologize once they came to the realization that they had indeed been the ones at fault. But I do. Because as a teacher, I continue to cling to the hope that adults in our society will model the same behaviors that we seek to cultivate in our young people. It’s an optimism that has been seriously dampened during the pandemic, but it has not died yet.

Patricia Kinsella, interim superintendent of the Pioneer Valley Regional School District said it best on Radio Boston this week when she said, “We all make mistakes — all of us. What’s important is that we repair our relationships when we discover that we’ve made an error.”

This message of restoration and repair is the one that we consistently use in our schools with young people. In fact, it stems from the concept of restorative justice, an approach to repairing harm that DESE has strongly supported in schools as a mechanism for interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline. The core premise of restorative justice is that it is OK to make mistakes. We learn from mistakes. But if our mistakes render harm, then it is also our responsibility to acknowledge the harm we’ve caused, and to make it right. In the context of restorative justice, apology — both the words and actions of apology — is accountability.

Our state leadership pointed fingers at districts and schools and educators first, rather than taking the time to investigate its own actions. When asked about the expired tests, DESE spokesperson Jacqueline Reis stated, “Districts that have expired BinaxNOW tests were told not to use them,” somehow implying that districts had gone rogue, and not passed out the tests from the state. In Boston, district spokesperson Jonathan Palumbo passed the blame on down to the school level, stating, "I have been asking around and it looks like some schools had a supply of tests from a previous shipment that we were not using. We have informed schools to not use those tests and are unsure why they were passed out today."

Advertisement

In both cases, rather than take responsibility, leadership sought to place blame.

Meanwhile, in my school this week, student and staff absences have been higher than I’ve ever seen in my 19 years as a teacher. Kids participating in the test and stay program express anxiety in the hours leading up to testing. They are worried about what the results of that testing will be. Will they test positive? Will they get sick? Will their desks be empty much like those of their peers are?

... state leaders chose to exacerbate, rather than mitigate, the stress of this moment. This is not OK.

As teachers, we are struggling to figure out whether to move ahead with new content, thereby negatively impacting kids who are sick at home, or whether to stay in review mode with the students who are in person, which also impacts their learning. Our profession has required us to re-invent ourselves so many times in the past 21 months, and now we are being asked to re-invent ourselves, to re-invent what schooling should be and do, once again.

And there is no clear, proactive messaging from the state about how we should approach this period of intense interruption. The only messaging is that of blame. It is hard, as someone who has dedicated her life’s work to the education of young people, to not feel angry about the utter vacuum of vision, and the speed with which our leaders seek to point fingers at the people whose daily labor is actually required to keep our schools open, and keep our students safe and supported and learning.

In the context of higher COVID case counts every day, over-taxed hospitals, 4-hour waits for PCR testing, crossing the threshold of 20,000 COVID-19 deaths in our state, and intense staffing shortages and student absences in schools, state leaders chose to exacerbate, rather than mitigate, the stress of this moment. This is not OK. It merits an apology. It merits a sincere and transparent effort to make things right.

As much as I wish our leaders would display the kind of behavior that I work to cultivate in our young people, it is my students who are currently modeling the approach we should take when harm is caused: to begin by understanding what happened, to learn how our choices affected us and those around us, to unpack what it means to make things right, and then to take the actions needed to remedy the harm.

An apology should not be too much to ask for in this context. And yet, our state leaders seem incapable of apologizing.