Advertisement

Commentary

'The Godfather' made Mario Puzo famous. But his best work is about about a woman like my 'Ma'

I read Mario Puzo’s megahit, “The Godfather,” in the early 1970s, along with most of the world’s population. As a feminist and a first-generation Italian-American, I had been baffled by the minor role women played in the novel. I knew from firsthand experience what powerful players women were in the Italian family dynamic.

“Women and children can afford to be careless. Men cannot,” intones the title character at one point to his son.

Really, Don Corleone? Not in my experience.

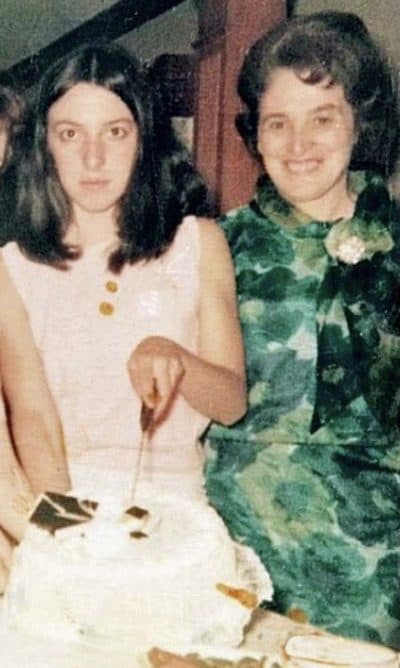

My mother grew up in a peasant family outside of Sulmona at the foot of the Apennines in central Italy, and she was the fierce beating heart of our family: strong, courageous and not careless in the least. She couldn’t afford to be careless. Widowed at the age of 43, my mother was alone and “unskilled,” raising three children in a country where she barely grasped the language.

I didn’t realize until I read “The Fortunate Pilgrim,” Mario Puzo’s second book, that the man could write with such love and sensitivity about Italian immigrants — and specifically about Italian women. I was so stunned by the emotional truth of his book that I wrote Puzo a fan letter (which went unanswered).

[Puzo's] beautifully told immigrant story fostered the beginnings of a deep empathy for my mother and others who came to America to build a new life for themselves and their children.

Lucia Santa Angeluzzi-Corbo, the main character of Puzo’s second novel, was an Italian mother very much like my own: a widow without marketable skills and with limited English raising children on her own. Her first husband had been “a chief without foresight, criminal in his lack of ambition for his family” and her second, Frank Corbo, had succumbed to madness. Raising six children alone in the teeming tenements of New York, Lucia Santa, like Vito Corleone, bemoans the carelessness of the opposite sex:

“That men should control the money in the house, have the power to make decisions that decided the fate of infants — what folly! Men were not competent. More — they were not serious.”

In my 20s, a struggling actor in New York City, I was just beginning to appreciate the emotional depth and force-field love that had surrounded me as a child — love I had regarded as suffocating then. Like Octavia, Lucia Santa’s first-born, I chafed against my family’s low expectations for me. Octavia wanted to be a teacher; I wanted to go to university. My family thought it would be a waste. “You’ll just get married in a few years and have kids,” they said. I was outraged at what I perceived as a dismissal of my intelligence.

But in the pages of Puzo’s book, my mother, the passionate woman I had resented all those years ago became familiar, and someone whose hopes and fears I could, at last, begin to comprehend. This beautifully told immigrant story fostered the beginnings of a deep empathy for my mother and others who came to America to build a new life for themselves and their children.

In luminous prose, Puzo describes these women as speaking...

“with guilty loyalty of customs they had themselves trampled into dust. The truth: these country women from the mountain farms of Italy, whose fathers and grandfathers had died in the same rooms in which they were born, these women loved the clashing steel and stone of the great city, the thunder of trains in the railroad yards across the street, the lights above the Palisades far across the Hudson…Audacity had liberated them. They were pioneers, though they never walked an American plain and never felt real soil beneath their feet. They moved in a sadder wilderness, where the language was strange, where their children became members of a different race. It was a price that must be paid.”

I picked the book up again in 1997 and discovered that Puzo himself had written the preface to the new edition. In it, he calls “The Fortunate Pilgrim” his best novel and his most personal one. Puzo describes his original plan for his second novel, the story of a struggling writer at odds with his ignorant family who stand in the way of his art: “to show my rejection of my Italian heritage and my callow disdain of those illiterate peasants from which I sprang,” he says in the foreword to that book.

Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind, I heard the words of my mother.

Mario Puzo

Instead, “The Fortunate Pilgrim” became a story about Lucia Santa, based on the author’s own mother, now the hero of the book. After receiving fantastic reviews — The New York Times called it a “small classic” and New York Magazine said “it could have put Puzo on track to be the Italian Malamud or Henry Roth” — the novel sank like a stone. Puzo had to take two jobs to support his family and, furious at himself for wasting 10 years on a “classic,” vowed to write a bestseller. That book — which used stories told to Puzo by his mother when he was a boy — became “The Godfather.”

In Puzo’s own words:

“Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind, I heard the words of my mother. I heard her wisdom, her ruthlessness and her unconquerable love for her family and for life itself, qualities not valued in women at that time. The Don’s courage and loyalty came from her; his humanity came from her….And so, I know now, without Lucia Santa, I could not have written ‘The Godfather.’”

So, the Godfather was a woman after all. I should have known.