Advertisement

Commentary

Compassionate release for aging prisoners isn't enough

Armand Coleman was 17 when he was arrested and sentenced to life in prison. Although Coleman was legally a child when he was arrested, he was tried as an adult and sent to serve his time in an adult facility. He served the first 20 years of his sentence in maximum security prisons, where he spent over a decade in isolation before he was given notice that he was going to be transferred to MCI-Norfolk, a medium-security prison.

You might think that moving from the violence of the max and the desolation of solitary confinement to the relative calm of the medium would be a cause for celebration. But for Coleman, the move felt more like a death sentence.

“At first, I didn’t want to go to Norfolk at all. That’s where lifers were sent to die,” he told me.

MCI-Norfolk is Massachusetts’ largest medium-security facility, housing around 1,200 incarcerated people. Norfolk is regarded as the “nicest” correctional facility in Massachusetts due to its college-campus-like infrastructure and purported focus on rehabilitation, and thus tends to be a dumping ground for lifers or folks serving longer sentences. Around half of the people currently incarcerated at Norfolk are serving a life sentence, and the average age of Norfolk’s incarcerated population is 48. Currently, the oldest person incarcerated there is 88.

As advances in health care and technology have enabled humans to live longer, older adults have become one of the most rapidly growing American demographics. The prison population is no different. Massachusetts is ranked second-highest in the nation for its number of older people who are incarcerated, with more than 15% of its currently incarcerated population over the age of 55.

With more people dying in prison of old age than ever before, legislators are left pondering what to do with the aging prison population. One proposed solution is compassionate release, a policy that advocates for medical parole for those who are terminally ill or incapacitated so that they may receive proper medical support and end-of-life treatment. The demand for compassionate release has increased over the past few years, largely due to COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a larger human rights crisis: health care for incarcerated individuals and health care for the elderly, two of the groups most devastated by the deadly disease. Compassionate release seeks to address the overlap of these two demographics. Advocates for compassionate release point out that beyond the moral obligation of offering individuals dignity in death, the policy has striking fiscal benefits. Whereas the typical incarcerated person costs the state around $70,000 per year, an elderly incarcerated person typically costs two to three times that much.

This push for compassionate release builds upon the past decade of criminal justice system reform in the state and country at large. One of these reforms played a large role in Coleman’s story. In 2013, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that life without parole for juveniles (those under 18) violated the state constitution. Due to this legislation and subsequent reforms, Coleman was given an opportunity to access programing within the prison that he had previously been disqualified from. He was also afforded the opportunity to access forensic experts. In 2019, he was granted parole and released after serving 28 years of his sentence.

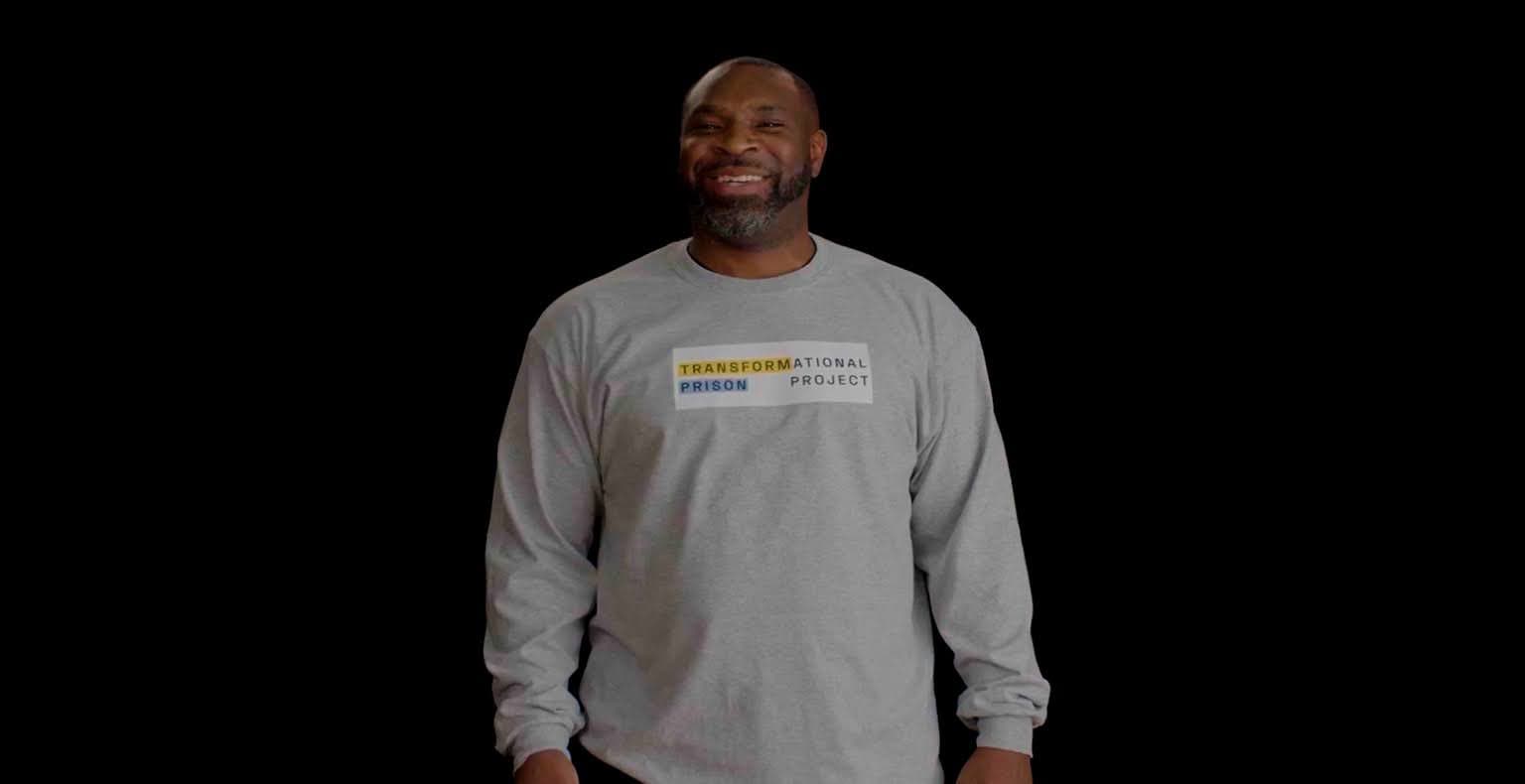

Coleman now serves as the executive director of the Transformational Prison Project, or TPP, a Boston-based organization centered around the practice of restorative justice. TPP seeks to bring together those who have been harmed and those responsible for harm so that they can engage in dialogue and build understanding and empathy toward those who have been victims of violent crime.

The organization, originally founded in 2013 by people incarcerated inside MCI-Norfolk, has now expanded beyond the walls and runs restorative justice circles in the community. Coleman is also in the process of launching a Youthful Offenders Coalition, aimed at supporting the successful reentry of youthful offenders like himself who have been released on parole.

While compassionate release is a great place to start, focusing on release alone as a measure of success paints an incomplete picture. In speaking about his own reentry, Coleman recalls the difficulty of adjusting to life on the outside.

Like many other returning citizens, he encountered obstacles as he re-entered society, from finding employment and housing, to navigating technology that hadn’t existed when he was locked up, to unlearning the trauma of growing up behind bars. These barriers can be particularly pressing on elderly returning citizens, who may lack a support system, struggle to find work and have pressing health needs. This pressure is, of course, exacerbated for those who have been sent home specifically due to their health issues through compassionate release. Once they are released, they might not have access to resources, be aware of how to navigate the health care system or have anyone to advocate for them.

And so, how can we expand upon the movement for compassionate release and extend into compassionate reentry? Coleman has a few ideas that he hopes to address with the help of the TPP and the Youthful Offenders Coalition, including housing assistance and mental health services. He has already begun the process — last month, the TPP chartered its first adult education digital literacy class with Maverick Landing Community Services and Mutual Aid Eastie.

Leaving prison shouldn't be a death sentence.