Advertisement

Commentary

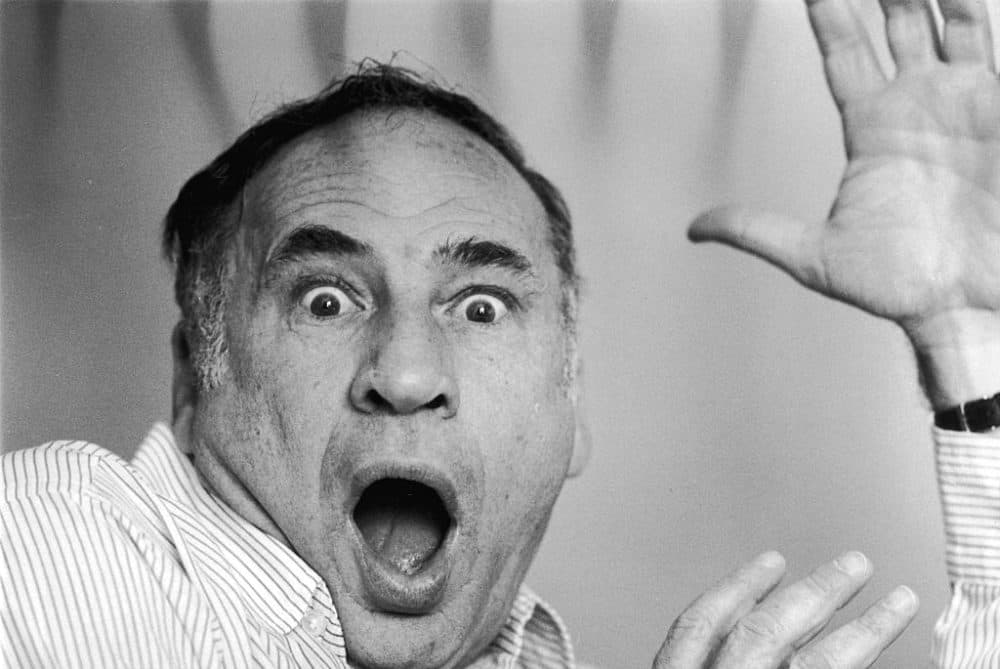

Life's absurd. Mel Brooks helps

Mel Brooks published his lovely and very funny memoir last year at the sprightly age of 95 — he turned 96 a couple of weeks ago — and my 12-year-old daughter and I listened to the audiobook during hours spent together in the car. Reader, he doesn’t just narrate. He sings! He recites favorite lines. It ushered in a season of Mel Brooks at our house. We’d return home and, with my two younger kids, watch whatever Brooks joyfully recounted to us that day.

Lots of things went back to normal between last winter and spring — or whatever normal is now — but the microcosm of our house remained solidly off kilter. My husband manages a topsy turvy emergency room, working shifts at all hours. I hit the peak of pandemic parenting burnout, all while the sun set before 6 p.m.

The thing we could do together, seemingly the only thing, without arguing, without stressing about COVID exposure or work schedules or the wildly varying temperaments of my three kids, was watch movies. Funny ones.

More than ever I’m cognizant of sending my kids out into a world that can’t -- or won’t -- keep them safe.

More than ever I’m cognizant of sending my kids out into a world that can’t — or won’t — keep them safe. It’s the hardest truth to hold while we still have to, somehow, simply go on about life. Brooks’ parody films are hilarious, sure. They make us laugh, and that feels good. But also, it’s their defiant absurdity that I find myself reaching for again and again.

At the end of the first chapter of his memoir, Brooks writes:

Comedy is a very powerful component of life. It has the most to say about the human condition because if you laugh you can get by. You can struggle when things are bad if you have a sense of humor. Laughter is a protest scream against death, against the long goodbye.

I lean heavily on jokes when I’m anxious, and I don’t just mean at dinner parties or job interviews. When I delivered my third baby via c-section — an hour of fully conscious major surgery — the operating room nurse said it was the most she’d ever seen a patient talk during that particular procedure. It wasn’t a compliment so much as an awed observation.

“Spaceballs” is already canon at our house, but this spring we watched it again, and again. Driving to and from soccer games we listened to how Brooks made “The Producers”: the original in 1967, then the Broadway musical in 2001, and film in 2005. “Young Frankenstein” was an instant hit. When I told my kids I was “Frankenstein-ing” a piece of writing — taking old parts and making something new — my son quipped, “It’s pronounced Frankensteen.”

When my 6-year-old tested positive for COVID just before Mother’s Day, we canceled plans, made cinnamon buns and watched “Robin Hood: Men In Tights,” again. When Robin says, “Watch my back!” and Achoo watches, then reports, “Your back just got punched twice,” it feels like the perfect metaphor for parenting.

On rainy weekends we streamed “Get Smart,” which I watched with my dad nearly every night when I was my kids’ age. My daughter bristles at how Max gets the credit while 99 does the secret agent heavy lifting, and she rightly calls out the stereotypes and tropes that haven’t aged well. Still, maybe my kids, like me, will think of my dad when they land a good cone of silence joke, a “would you believe ... ” or a “missed it by that much.”

So much of what I’m sharing with my kids now, as well as what I’ll save for when they’re older (looking at you, “History of the World: Part 1” and “Blazing Saddles”), I watched with my own parents. Love language in my family, from age 6 to age 78, sounds something like this: “Walk this way,” “What hump?” “It’s good to be the king,” and “Please, please, don’t make a fuss. I’m just plain Yogurt.”

Advertisement

I had a professor in college who wore electric purple suits and extolled humor as the highest point of connection one person can share with another. Everything else trickles down or grows deeper because of it, he said, even love.

I think about this theory all the time, including just the other night when my husband and I had to pause the HBO show “Our Flag Means Death” — twice — because we were both laughing so hard. Less than an hour earlier, I’d gone through an entire box of tissues, caught up in an anxiety spiral brought on by the end of school, and our family’s move to a new town, a new house, new everything. More change!

I had a professor in college who wore electric purple suits and extolled humor as the highest point of connection one person can share with another.

Around the middle of the book, Brooks recalls an interview he and his wife Anne Bancroft did for “The Today Show,” in which she said, “When I hear his key in the lock at night my heart starts to beat faster. I’m just so happy he’s coming home. We have so much fun.” This, I think, is as good a goal as any.

Then, towards the end, all the way on Page 451, Brooks reiterates, “If you can laugh, you can get by. You can survive when things are bad if you have a sense of humor.”

I think he’s also saying, while this life is messy and mercurial, and you often can’t control it, and sometimes, like Maxwell Smart, you might even feel like you’re facing extreme danger at every possible moment, you can still respond absurdly, defiantly: “And loving it.”