Advertisement

Commentary

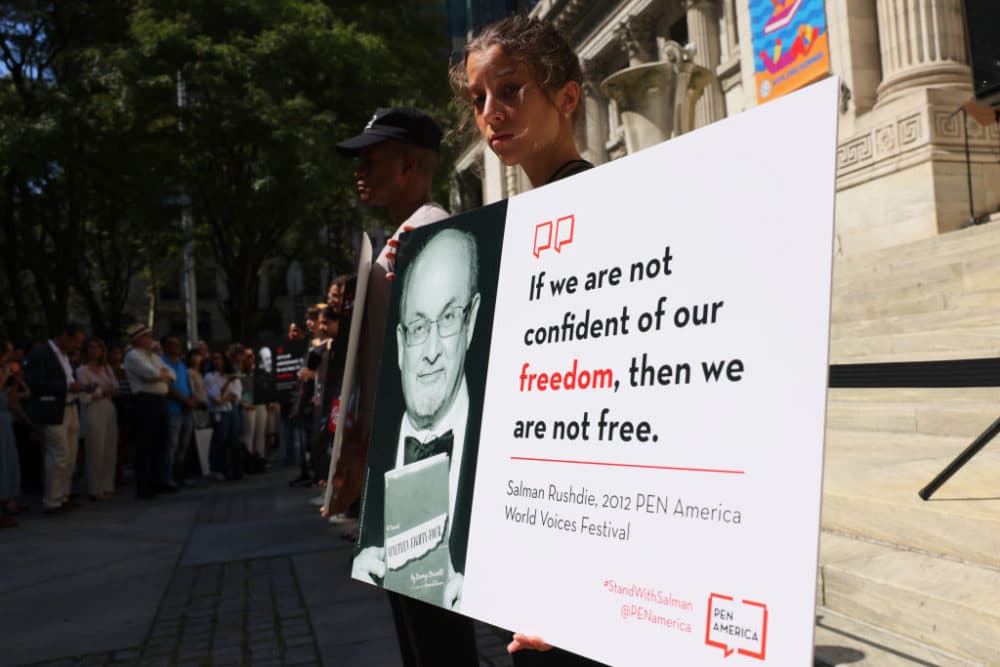

What the attack on Salman Rushdie tells us about extremism

In August, New Jersey-native Hadi Matar tried to murder Salman Rushdie over a book published nearly a decade before he was even born. Matar admitted from prison he had only ever read two pages of "The Satanic Verses."

So what motivated this young American to carry out Ayatollah Khomeini’s notorious fatwa, 33 years after it was issued?

True, Matar’s parents hail from a part of Lebanon where the Iranian regime enjoys support. But his mother, Silvana Fardos, hardly fits the profile of a Hezbollah supporter. Before the FBI knocked on her door, she had never even heard of Rushdie and could not fathom why her son would try to murder someone. The young man who attacked Rushdie physically resembled her son, but his actions were no longer recognizable.

Every day, parents like Fardos call my organization’s helpline in a desperate quest to understand and fight the demons that seem to have taken hold of their children.

Some parents are filled with shame. Some ask how they could have let their child’s mind be stolen. Others wonder what they could have done differently. Many take their loved ones’ extremist actions as a reflection of their own parenting failures and blame themselves. Many are so afraid of being judged critically by outsiders for their “failures,” that they keep their pain to themselves. Sometimes their closest friends or relatives remain unaware of what they endure. As a result, the families of the extremists end up just as confused, disempowered and isolated as their loved ones.

In the past two years, our hotline has received more than 360 calls. We’ve talked to the parents and guardians of young men who marched in Charlottesville; mothers and fathers of New York City teenagers who are being recruited into ISIS; and to relatives of Antifa members from Pacific Northwest, sent to fight for Kurdish militias in Syria.

For vulnerable minds, a hateful ideology serves as a grand cause — it hands the microphone to a person’s pain, while blaming it on an evil outside force.

In these situations and others, we’ve learned that hate has become a drug of choice, and the resulting extremism works similar to addiction: It numbs angst.

These families come from a wide cross section of American society: Christian, Muslim, Jewish and Hindu — rich, poor and middle-class — white, Black, Hispanic, Asian and more. We see first-hand that hate has no color, and that no family is immune from the demons of extremism.

We all possess brains that are susceptible to unaddressed trauma and a deep sense of injustice. For vulnerable minds, a hateful ideology serves as a grand cause — it hands the microphone to a person’s pain, while blaming it on an evil outside force. The staff at Parents for Peace includes former extremists, including former KKK members and former Islamists, who were once seduced into extremism — they understand first-hand, how appealing messages of victimhood and scapegoating can be. In conversations with family members, they bring their experiences to conversation-based interventions.

Advertisement

According to news reports, Matar was born and raised in California. His parents divorced when he was a teenager, and his father returned to southern Lebanon. After a difficult visit to his father four years ago, Fardos said her once outgoing son returned from Lebanon introverted, locking himself in her basement. He filled his Facebook page with photos of Iranian regime leaders and even made a fake driver’s license with his picture beside the name of two top Hezbollah leaders.

Matar’s case mirrors what we see time and again with impressionable young recruits to the KKK and white supremacist movements, and extremist networks like Antifa and Black Supremacists. The typical target is a young person reeling from an identity crisis — and often with untreated PTSD — who seeks a sense of belonging, brotherhood and someone to blame. Rather than do the hard work of healing, they latch on to a prominent scapegoat. For Matar, Salman Rushdie fit the bill.

Or consider the Boston marathon bombers. In a new three-part documentary series, “The Murders Before the Marathon,” journalist Susan Zalkind reveals that Tamerlan Tsarnaev resorted to conspiracy theories and radicalization after his dream of pursuing success through boxing was shattered (the new rules prohibited the non-citizens from participating in the national events). As Boston.com reported:

After his singular focus was taken away from him, Tsarnaev began to read extremist literature and embrace conspiracy theories. He read English language versions of a propaganda publication created by Al-Qaeda and took a shine to conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. He also became a virulent anti-Semite, and fought regularly with Mess and Teken about Israel.

Without absolving these young people for the consequences of their terrible decisions and actions, we can also see them as victims of traffickers. Cognitive science tells us that the human brain continues to develop through the age of 25. The master manipulators who drive extremist movements, sniff out susceptible yet naïve and wounded young people, preying on their identity crises.

Intervening in these cases before violence occurs requires recognizing extremism as a powerful and addictive drug. Just as American society has developed tools to treat addiction, we need a parallel public health push to sensitively and effectively tackle the drug of hate, and to deepen awareness among educators about the dynamics of radicalization.

Editor’s note: If you know someone struggling with extremism, call Parents For Peace helpline: 1-844-49-PEACE